The chocolate price spike: what’s happening to global cocoa production?

Bad weather and disease outbreaks are hitting cocoa production in West Africa.

The Easter Bunny is having an expensive year. Cocoa prices are going through the roof. In the last week, they’ve surged to more than $10,000 per tonne. That’s nearly twice the record set 50 years ago.

What’s going on, and what does it mean for the future of cocoa production?

Most of the world’s cocoa is produced in West Africa

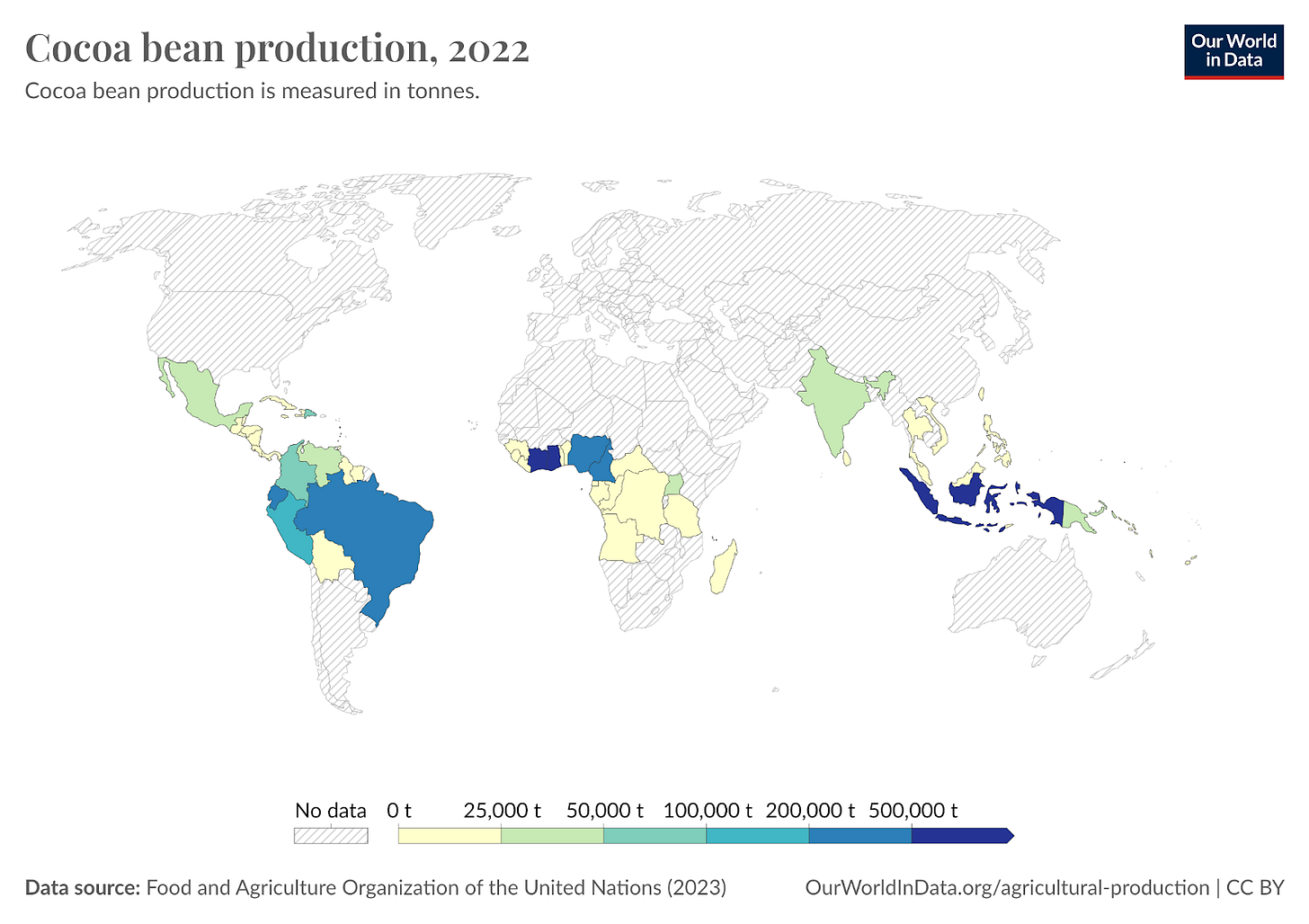

The world produces nearly 6 million tonnes of cocoa beans each year. Almost two-thirds of this comes from West Africa. Most of the rest is produced in South America and Asia.

The chart below shows each region’s share of global production.1

Production is even more concentrated within West Africa. See the chart below (you can explore it for other countries here). The Ivory Coast produces around 38%, and Ghana 19% of the world’s cocoa beans. That’s almost 60% combined.

In Asia, production is dominated by Indonesia, and in South America, it's a combination of Brazil, Ecuador and Peru.

Bad weather and disease outbreaks have hit cocoa production in West Africa

Agriculture in West Africa is vulnerable to the El Niño (warm) phase of the ENSO cycle. It often leads to drier and warmer conditions. It has suffered intense heatwaves and drought in recent months. While this is expected during El Niño years, climate change could be making these conditions more intense.

The biggest impact on cocoa hasn’t been the temperature itself but the impacts of rainfall extremes on disease outbreaks. West Africa experienced extreme wet conditions late last year, driving an outbreak of “Black pod disease”. This is a fungal disease which tends to spike just after the wet season. If it’s not treated, it can destroy an entire harvest. There are copper-based fungicides that can control the disease and reduce these losses but farmers don’t always have access to – or can’t afford – these chemical pesticides.

This extreme rain was followed by extremely dry conditions, which has helped the spread of another disease: the “Swollen shoot virus”. This disease only occurs in West Africa and is spread by insects called “mealybugs”. Cacao trees see large yield declines of up to 25% in the first year of infection and 50% in the second.

It’s really hard to tackle. Ghana has spent almost a century trying to eradicate it. There is currently no chemical treatment for the virus (or at least I’m not aware of one). Swollen shoot virus is usually managed by getting rid of the visibly infected trees and their neighbours. This means cutting down a lot of trees and plantations. Even then, it’s hard to eradicate the disease completely.

The International Cocoa Organization and cocoa traders estimate that global production could drop by around half a million tonnes this year. That’s around 10% of the world’s usual harvest. This comes off the back of two previous ‘deficit’ years, meaning there is a large shortfall of supplies.

Cocoa production is also under pressure from mining and low farmer incomes

El Niño – and the knock-on impacts of extreme weather – has been the big hit for cocoa this year. But it’s not the only problem the crop faces. Cocoa production in West Africa is facing other major barriers.

Illegal gold mines have taken over large areas of productive cocoa lands in Ghana. It’s often hard for small-scale farmers – living on very low incomes – to resist selling some of their land for mining. As one cocoa farmer put it: “Every month he pays me $500 and I am happy with that because I am not going to make such an amount of money in my cocoa business," she said. Other landowners are violently forced off their land, with no payment at all.

Many cocoa-farming households live below the international poverty line, and most live on less than a “living income”: the amount needed to afford basic living standards.2 If farmers were earning a healthy income, there would be less temptation to accept these offers. Better and fairer trade agreements that make sure that farmers get a good cut of the final cocoa price are essential. But, the current domestic pricing system in Ghana and the Ivory Coast can also be damaging.

The skyrocketing price of cocoa should be good for farmers. Those who have seen a reduced yield this year should be able to top up their income with higher returns on the harvest they did get. This is not happening. Governments in these countries set cocoa prices based on sales from the previous year.3 The global price is above $10,000 per tonne, but farmers are receiving a fixed price between $1,600 and $1,800 per tonne.4 While this guarantee provides a “price floor” for farmers, they lose out when prices are high. It’s farmers in other – more open – markets such as Brazil, Peru, Ecuador and Indonesia that are benefitting from the spike.

This is bad news for West African farmers. Without healthy returns, they can’t protect their crops from disease or invest in more productive harvests next year. Aging and less productive trees are a more chronic – and growing – problem, which could lead to a more structural decline in cocoa production in the region.

Financial markets are also driving the recent price surge

The dramatic price hike is not only driven by the physical reality of this year’s harvest. It’s also been driven by the financial chaos that occurs with such dramatic and rapid price surges.

Traders with physical cocoa stocks benefit from rising prices. But they’ll also try to protect themselves from falls by betting on “short positions”. If prices fall, then these bets will provide some cushioning for their “long position”. If prices keep rising, their gains will offset their hedging money.

The problem is that collateral for their future bets can become too expensive, forcing some to close their positions. This pushes up prices even more.

The market exchange is trying to reduce this volatility by putting limits on how many tonnes traders can buy. But these limits are reduced progressively throughout the year, so won’t have an immediate effect on prices.

What might the future of cocoa look like?

Let’s summarise the cocoa problem down to its fundamentals.

Most of the world’s cocoa is produced in a handful of countries. These countries are highly susceptible to extreme and cyclical weather and crop diseases. This is likely to get worse with climate change. And farmers do not earn enough to properly invest in pest management, and more productive crops.

One obvious solution at a global level is to diversify cocoa supplies. That means larger markets in South America and Asia so the global market is less sensitive to shortfalls from West Africa, where Black pod disease and Swollen shoot virus are concentrated. Farmers in other regions – seeing the recent high prices – might be investing in more cocoa production already. I would not be surprised to see countries such as Ecuador, Peru and Brazil become the dominant producers in the next decade or two.

But that fails to address the root of the problem for farmers in Ghana and the Ivory Coast. They do not have the money to invest in more resilient or protected crops. In the short term, the governments in these countries could lift the fixed price, and pay more to farmers. But if we want a sustainable system, farmers will need to be paid a bigger cut for the cocoa that ends up in our chocolate bars. Fail to do so, and many of the world’s poorest farmers will be left behind.

Next year there could be more disruptions to global cocoa markets. The European Union is due to introduce its Deforestation-free Regulation (EUDR) that bans the imports of any beans that have been produced on recently deforested land. This is a big issue for West African farmers since Europe is its biggest export market and cocoa farming is a main driver of deforestation. This is a positive step forward for the environment, but makes things more complicated for cocoa bean farmers. Monitoring and tracking every cocoa bean – if that’s even achievable – will add additional costs to different actors in the system. How these costs are distributed, and whether West African farmers need to export elsewhere remains to be seen.

This data comes from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

You can explore it in our work on Our World in Data.

van Vliet, J. A., Slingerland, M. A., Waarts, Y. R., & Giller, K. E. (2021). A living income for cocoa producers in Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana?. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems.

Staritz, C., Tröster, B., Grumiller, J., & Maile, F. (2023). Price-setting power in global value chains: The cases of price stabilisation in the cocoa sectors in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. The European Journal of Development Research.

I've seen mixed reports: data from Bloomberg suggests this price is equivalent to around $1,600.

However, there are reports that this producer price was increased last year and was equivalent to around $1,800.

Part of this difference might be explained by conversion rates from local currencies.

Great article. I'm Ghanaian myself. Since independence, the 1st President Kwame Nkrumah used a state owned marketing board to pay a fixed price to cocoa farmers, collect all the beans and sell it on international markets.

The marketing board was supposed to act as a "countercyclical cushion" - when cocoa prices are low, pay farmers more, when cocoa prices are high pay farmers less. Instead it just squeezed profits from the farmers, and people like my grandfather who was a well off cocoa farmers felt squeezed from Nkrumah's low prices, while Nkrumah used the cocoa export revenues to fund his industrialization and infrastructure projects.

The result was farmers would go to nearby Ivory Coast to sell cocoa for higher prices under Felix Houphoeut Boigny's relatively more liberal cocoa policies.

Right now Ivory Coast is not only going to make more money from high cocoa prices but they have been diversifying and adding value:

Not only does Ivory Coast make $3.33B in cocoa beans, but Ivory Coast now makes $1.1B in cocoa paste, $500M in cocoa butter, $200M in chocolate and $195M in cocoa shells (2022 data):

https://oec.world/en/profile/country/civ

Ghana, although its the second biggest cocoa market in the world, makes less money selling cocoa beans than Ivory Coast sells in cocoa paste ($1.08B).

https://oec.world/en/profile/country/gha

Ghanaian firms aren't doing as well diversifying and adding value:

Ghana Cocoa paste $450M, cocoa butter $268M, cocoa powder $114M, chocolate $24M. (2022 data)

Hannah, one would assume large consumers of cocoa, Hersheys, Mars, and Nestle etc have hedges and/or long term contracts in place so the 4x market price increase y-o-y would most impact small producers so that might be an interesting follow-up. Given the market floors paid to farmers in Ghana, who profits by the windfall might be another interesting angle. Great Work!