Electric cars don't work as well in the cold, but they still work very well

The range of electric cars falls by around a fifth in freezing temperatures.

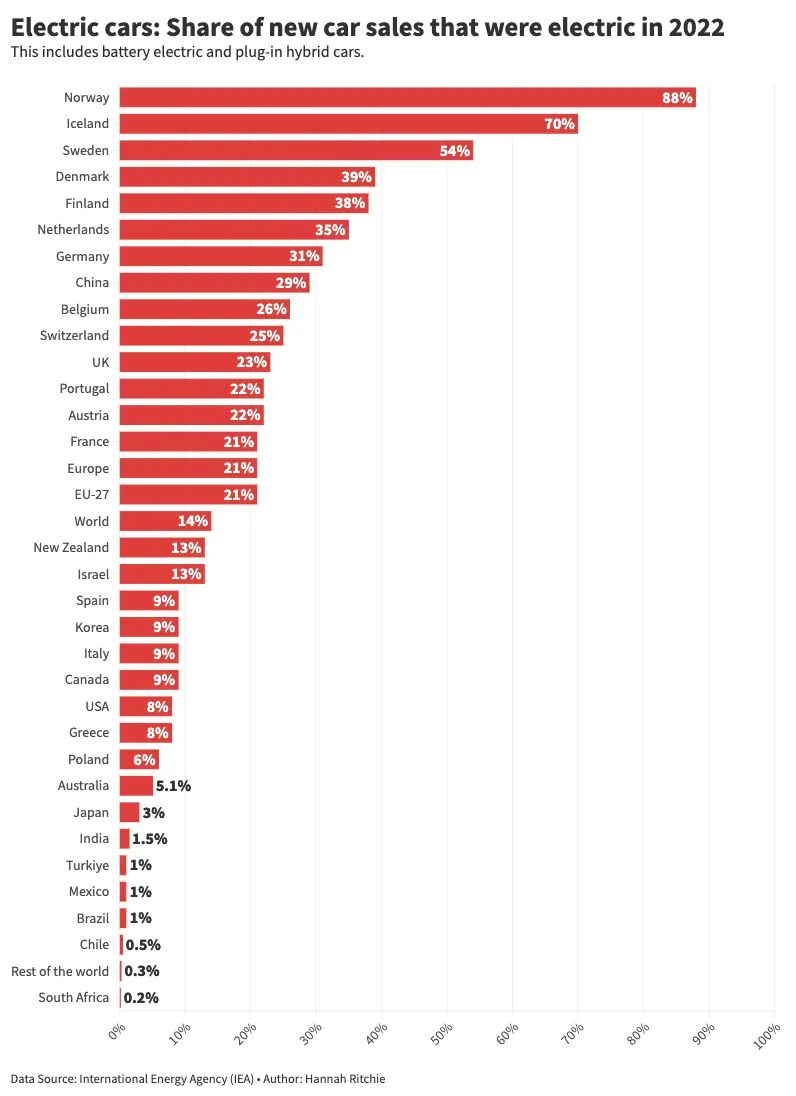

There is one country in the world where almost every new car is an electric one. Hardly anyone buys a petrol or diesel car. Nine electric cars are sold for every gasoline one.

That country is Norway. One of the most-Northern and coldest countries in the world. Four or five months of the year, temperatures can reach below zero (in degrees Celsius).

Let’s look at the other countries where electric vehicles (EVs) are most-popular. In 2022, Iceland, Sweden, Denmark and Finland rounded off the top-five. Notice anything that connects the EV enthusiasts? They’re all Scandanavian. At high latitudes. Cold, harsh winters.

To make this point even clearer, let’s plot each country’s EV sales against its latitude. Here, the latitude is that of its capital city, which is not perfect (many people in Canada, for example, will be living at colder latitudes than Ottawa) but gives us a reasonable estimate of large population centres where people will have electric cars.

We can see that the countries where EVs are most popular are at the highest latitudes.

Let’s get one thing straight: these countries don’t have lots of electric cars because they’re cold. As we’ll soon see, low temperatures do have a negative impact on performance. They have lots of electric cars despite it being cold for a lot of the year.

If the cold was as big of a deal as many people claim, the markets for EVs in Scandinavia would have crumbled. Instead, EVs are thriving.

Cold temperatures reduce the range of electric cars by around one-fifth

Electric cars do lose some of their performance in the cold. This is because of how a battery works. It relies on reactions firing – moving from the anode to the cathode. That’s the storage and release of energy. When it’s cold, these reactions slow down. This is not a problem that’s specific to cars: the battery in your phone and laptop also dwindles a bit in the cold.

For EVs, this means two things: the range of the car – how far it can travel on a single charge – is reduced, and it takes longer to charge.

How much of a car’s range do we lose?

It wasn’t easy to find comparable, public data on this. The best source I could find was the Norwegian Automobile Federation (NAF), which has done some of the most extensive testing I’ve seen. For several years, it has done winter and summer tests on more than 50 different EVs. These tests are controlled to keep the conditions between the cars constant. In its Winter 2022 test, the cars were taken on a standardised driving route, with the temperature varying between 0 and minus 10 degrees Celsius (that’s 32 down to 14 Fahrenheit).

They drove each EV until the battery ran out, and compared its range to its advertised one. This advertised range is the result of the so-called ‘Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicle Test Procedure (WLTP)’: it’s the official exam for every EV and is there to make sure that manufacturers are reporting their cars’ range in the same way. The WLTP reports how far a car travels on a full charge, while driving continuously at 30 miles per hour in summer conditions. That’s the range that you see on the car label.

Unsurprisingly, every car in the Norwegian winter test had a lower range than advertised. But the amount varied by model. I’ve shown many of the results in the chart.

The average drop in range was 19%. So, if you had a car with a stated range of 450 kilometres, you might only get 364 kilometres on a single charge in winter.

The best-performing cars were the BYD Tang and the Tesla Model Y: they lost just 11% of their range. At the other end, the Skoda Enyaq iV80 lost a whopping 32; a result that was so controversial that the Norwegians had to test it again with another car (they got the same result, so it seems it wasn’t a fluke).

These results are very consistent with results I’ve seen elsewhere. Most studies report a 10% to 20% drop in range in cold temperatures, with some cars losing as much as one-third.

If you’re an EV owner, this is important to know. In fact, I think cars should also have a ‘winter range’ label, so that drivers know what to expect. Only reporting the range in perfect conditions is misleading.

This drop in range will not be a dealbreaker for most drivers. Most models are still getting 300 to 400 kilometres or more, even in freezing temperatures. Most car journeys are under 10 kilometres.

In the US – where people tend to drive more than in Europe and other countries – almost 80% of car trips are less than 16 kilometres (60% are shorter than 10km). Just 5% are longer than 50, so the percentage that gets anywhere close to 300 kilometres is incredibly small. As long as people have somewhere to charge their car throughout the week (most can probably charge once a week), the shorter range will almost never be an issue. It doesn’t seem to be a big problem in Norway, Sweden or Finland.

Manufacturers are working to improve battery performance, so maybe this will become even less of an issue. Some have already installed heat pumps in new models to reduce the temperature drop.

Cold temperatures also increase charging times by around 10 to 20%

People also worry about how long it takes to charge their car in the cold. The NAF tested this too. They took the same suite of electric cars, and had them driven until the batteries run down to less than 9% charge. They then tested how long it took to get them up to 80%, using a fast charger. They compared this time in the summer and winter.

The average time in the winter was 37 minutes, compared to 33 minutes in the summer. That’s around 10% longer. Not too bad. There were a few – such as the BMW iX – that took quite a bit longer in sub-zero temperatures. Their charge time increased by around a third. Some models, though, managed to charge just as fast in sub-zero temperatures. They do this by giving the option to quickly pre-heat the battery, which means that it’s ready to go once you start charging.

Another test is to see how far a car can go after 25 minutes of charging. The average was 225 kilometres. Some got more than 350. Again, not bad for a pit-stop break in freezing temperatures.

To be clear: a sceptic is right when they say that “EVs are not quite as good in the cold”. They’re not right when they say “EVs do not work in the cold”. Sub-zero temperatures reduce the range of cars by around 10% to 20%. It also increases the charge time by around the same percentage.

But given the range of most EVs is now well over 250 kilometres (often reaching 400 or 500 kilometres), a small drop has very little impact on the average driver. This point becomes obvious when we look at real adoption rates across the world. The coldest places have fallen in love with EVs, not because of these downsides, but in spite of them.

I want to be the first to say this, because the first one is definitely being helpful and not annoying or pedantic.

The capital of Canada is not Toronto.

Claro y ameno con información muy útil. Gracias¡¡