Eating local is still not a good way to reduce the carbon footprint of your diet

A recent paper claimed that 'food miles' accounted for 20% of food emissions. But this is wrong.

What you eat matters much more for your carbon footprint than where your food has come from. Your local beef emits more than your soy shipped in from South America. Plant-based foods nearly always have a lower footprint than animal produce. It’s true, regardless of how many miles it has travelled to reach you.

This is a point I made prominently in one of my most-read articles on Our World in Data:

A recent paper in the journal Nature Food seemed to go against this.1 It claimed that ‘food miles’ account for nearly 20% of food emissions, and that eating locally is important to reduce them.

But the study’s conclusion that ‘eating local’ would make a big difference to the carbon footprint of food isn’t supported by its results at all. Here I’ll explain why.

Eating locally doesn’t make a huge difference because transport is a small part of the carbon footprint of most foods

First, let’s quickly see why eating locally doesn’t make a big difference. If you’ve read my work before, and already know the reasons why, you can skip to the next section.

The rationale makes sense: travelling emits CO₂. We mostly still burn fossil fuels to power our cars, planes, trains, and ships. The further our food has to travel, the more CO₂ we produce. It’s true: moving our food around does come with a climate cost. But, importantly, transport emissions are usually small compared to the emissions generated on the farm to grow the food.

Transport is just 5% of food emissions.2 Here we’re talking about emissions from ‘food miles’. Keep this definition in mind – we’ll come back to it later.

Food mile emissions are the emissions caused by the transport of food from the point of production to consumption.

It’s moving the food from the farm to processing or distribution centres, to the shop or market, and sometimes includes the consumer driving them home. It’s about moving the food, not anything else.The reason this number is so low is because most food that is transported internationally comes by boat. And, shipping is very carbon-efficient. Per kilometre, it emits 10 to 20 times less than trucks on the road. And around 50 times less than flying. Food that comes by plane – air-freighted food – does have a hefty carbon footprint but, very little of our food comes this way. Your soy and avocados are not coming by plane.3 They’re coming by boat.

Surprisingly, more than 80% of the CO₂ from food transport is produced by trucks. That means most emissions come from moving food around domestically not internationally. Flying food around is just 0.4% of food transport emissions.

Most of the emissions from food come from land use change and production on the farm. What matters most for these emissions is the type of food you’re eating. These differences can be massive. Producing 100 grams of protein from beef can emit 10 to 100 times as much as producing it from peas or beans.

Emissions from transport are tiny compared to these differences. That’s why what you’re eating usually matters much more than how far it has travelled.

‘Food miles’ don’t account for 20% of food emissions, unless you change the definition of ‘food miles’

Let’s get back to this new study. It claimed that ‘food miles’ account for almost 20% of food emissions. That’s 3.5 to 7.5 times higher than previous estimates.

But this isn’t true. The only way ‘food miles’ account for 20% of emissions is if you change the definition of ‘food miles’. That’s what the authors did.

As the authors note in their paper, there is an established definition of ‘food miles’. Scientists use it, and it’s how most of the public understands it. We looked at it earlier.

‘Food miles’ is the distance food is transported from the point of production to consumption. It doesn’t include the transport of agricultural inputs or fuel. In this new study, these emissions from transport in upstream processes – that’s the transport of fertilizers, pesticides, machinery, livestock, and cooking fuels – were included.

By combining transport emissions from moving food around (food miles) and the transport of agricultural inputs, the authors estimated global food transport emissions to be 3 GtCO₂ per year. That would be almost 20% of food system emissions.

But, if we go by the standard definition of ‘food miles’ – as the transport of food alone – their results are not that different from previous estimates. These food mile emissions were just 1.4 GtCO₂ per year. That’s equal to 9%, not 20% of food emissions.

And, that would be 80% higher than the previous leading estimates. Not 3.5 to 7.5 times higher. As I’ll explain soon, I still think their estimates of food mile emissions are an overestimate.

In the chart, I’ve compared the results of this study with estimates of transport emissions from older global analyses from Poore and Nemecek (2018), and Crippa et al. (2021).

The study’s logical conclusion would be to eat food from countries that produce fertilizers and pesticides rather than eating locally

Adopting this new definition of food miles matters for what we’d recommend as climate solutions.

If food transport made a large contribution to food emissions then eating more local food would be an appropriate and effective recommendation. But, this isn’t the obvious conclusion under the ‘new’ definition.

In the study, upstream processes – including the transport of fertilizers, pesticides, machinery, livestock, and fuels – emit more than the movement of the food itself (1.6 GtCO₂ vs. 1.4 GtCO₂).

‘Eating locally’ wouldn’t be an effective way to reduce emissions because it wouldn’t tackle the transport of agricultural inputs. One of the following recommendations would make more sense:

All countries source food from countries that manufacture agricultural inputs;

All countries in the world manufacture their own fertilizers, pesticides, and machinery.

Either of these recommendations would be a disaster.

What’s odd is that, by the study’s new definition, you could source all of your food locally – even producing it on your own farm – and still have high ‘food miles’. This would happen if you were importing machinery, fertilizers, or fuels for cooking.

The study’s own results don’t support the ‘eating local’ recommendation

Here’s another reason to doubt the ‘eat local’ recommendation. The authors (almost) state it explicitly in their own paper.

The study included a modeled scenario where all countries sourced all of their food domestically.

In this local scenario, the world would reduce food emissions by just 1.7%.4 Less than 2%!

The results don’t support the ‘eating local’ recommendation. They show the opposite: it’s not an effective recommendation at all. Even in an extreme scenario of completely domesticated food consumption, cutting out transport wouldn’t make much difference.

This reduction is so small because a lot of the savings from reduced international transport would be offset by increased transport of food domestically. We would replace shipping miles with truck miles which emit 10 to 20 times more CO₂ per tonne-kilometer.

You could argue that if you went very local – not just eating food produced in your country, but produced from your neighbouring farm – that you’d cut out the hefty emissions from trucking. That’s true, but not realistic in the world we now live in. Most people live in cities or towns. They don’t have farms next door.

An extremely localized food system won’t work in the modern world.

The numbers don’t add up: the study also overestimates food transport emissions

When we compared the recent study to previous papers we saw that emissions from food transport were 80% higher than previous estimates.

I think this is an overestimate.

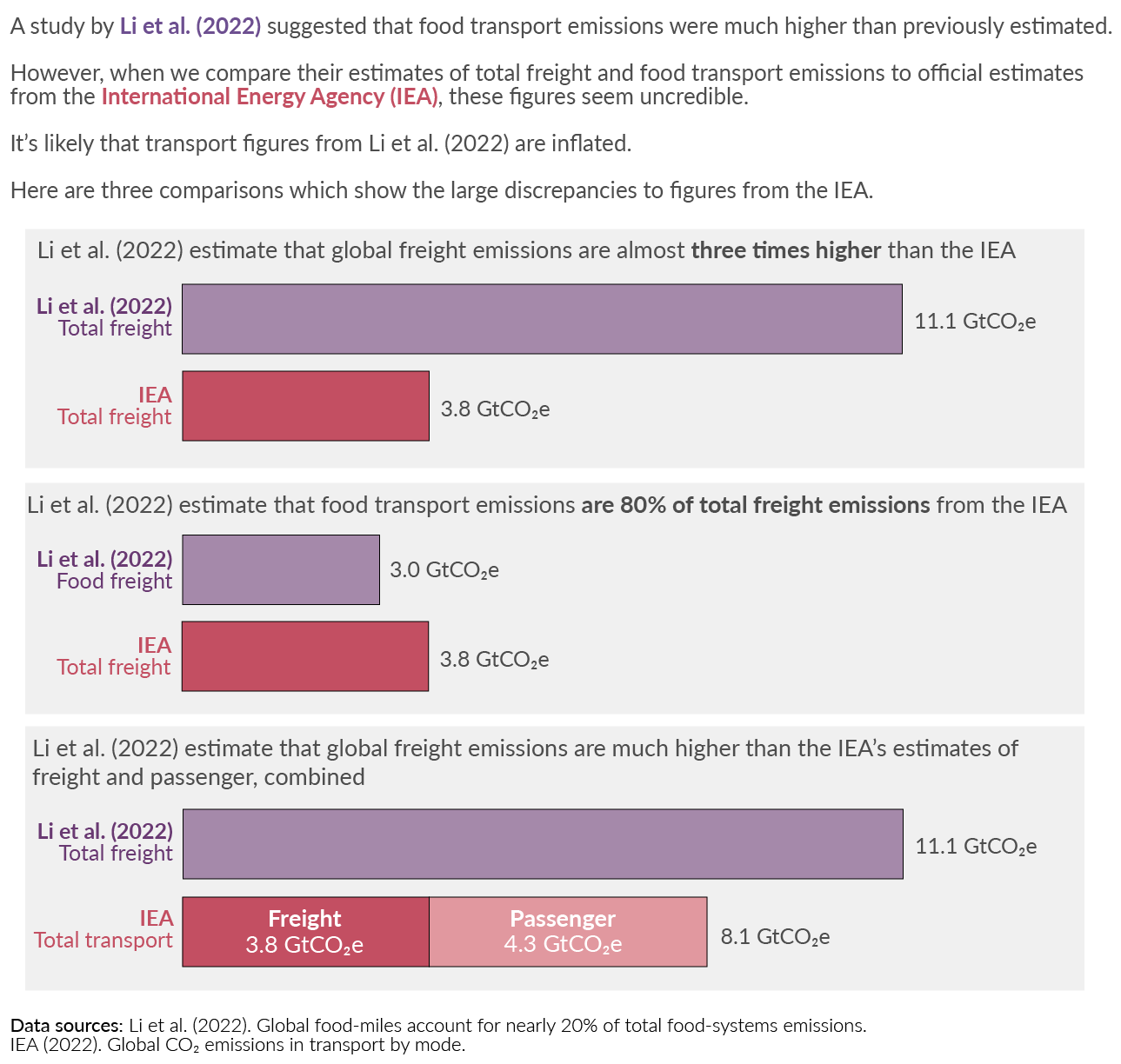

Let’s compare the study’s estimates of freight emissions to the figures published by the International Energy Agency (IEA).5

The IEA estimates that global freight – that is, moving all goods around, not just food – emitted 3.8 GtCO₂ in 2018. That’s the first bar in the chart below.

In this recent study, the authors estimate that global freight emitted 11.1 GtCO₂.6 That’s three times higher than the estimates from the IEA.

One-quarter of this – 3 GtCO₂ – came from the food system. That’s shown in the second bar.

These numbers just don’t make sense. This new study would imply all of the following:

Global freight emissions are three times higher than estimates from the IEA.

‘Food mile’ emissions are almost as big as the IEA’s estimates for all freight combined (3 GtCO₂ from food, versus 3.8 GtCO₂ from all freight).

Global freight is bigger than the IEA’s estimates of freight and passenger transport combined.

All of these conclusions seem wrong.

There are two possibilities here.

The first is that the world has been massively undercounting transport emissions. If the authors thought this was true, this would totally transform our understanding of global greenhouse gas emissions. They should have published that earth-shattering conclusion in a climate or transport journal, not a food one.

The second possibility is that the authors have included assumptions that inflate freight emissions. I think this is the case.

Without providing an exhaustive list, there are at least several places where their assumptions are likely to overestimate emissions:

It assumes that fruit and vegetables are always transported under temperature-controlled conditions, which emits a lot more CO₂. But this is not the case: many vegetables, such as onions and potatoes, are not usually temperature-controlled.

It assumes that this transport is temperature-controlled in every country. That’s also not true. But this is not true in many low- and middle-income countries. Lack of refrigeration is one of the big reasons for food losses in supply chains.

There are some unexplained, odd assumptions about how fuels are transported. For example, they assume that a lot of coal is transported on the road – and even some by plane – when the vast majority is transported by rail. Adding lots of these faulty assumptions up could get you to freight emissions figures that are too high.

‘Eat locally’ is not an effective way to reduce emissions

That brings us to a few overarching conclusions.

The first is that the new food paper probably overestimates transport emissions, by a lot.

The second is that, even if these figures were correct, the study’s results don’t support the recommendation that ‘eating locally’ is an effective way for someone to reduce their carbon footprint.

Remember, the authors estimate that a completely nationalised food system would reduce food emissions by just 1.7%. Hardly a game-changer.

What’s much more effective in reducing emissions is eating less meat, especially beef, and lamb. Reducing food waste. Improving crop yields and productivity to reduce land use and deforestation.

This is the message that should be clear to consumers. Instead, they get the message that ‘eating locally’ matters a lot. That’s appealing to many because it sounds and feels right.

But when we step back to look at the data, it’s not effective at all. In fact, it runs the risk of backfiring and making things worse. If people switch from imported plant-based foods or chicken to local beef, their carbon footprint will rise.

Li, M., Jia, N., Lenzen, M., Malik, A., Wei, L., Jin, Y., & Raubenheimer, D. (2022). Global food-miles account for nearly 20% of total food-systems emissions. Nature Food, 3(6), 445-453.

These numbers come from two leading global analyses of food emissions. Both studies estimate that transport – moving the food from the farm to processing centres, to distribution, right through to retail – accounts for around 5% of emissions.

Poore, J., & Nemecek, T. (2018). Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science, 360(6392), 987-992.

Crippa, M., Solazzo, E., Guizzardi, D. et al. Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nature Food (2021).

I compare these studies here: https://ourworldindata.org/greenhouse-gas-emissions-food

It's sometimes hard to identify which foods are air-freighted. They should have a label, so we know which ones to avoid if we're trying to be climate-conscious.

Flying food around is expensive. The only reason companies would do it is if the food is perishable and will 'go off' quickly. Or if 'freshness' gets them a massive premium. This is usually perishable fruits and vegetables such as berries and asparagus.

Check the label for where these are produced. If it's continents away, then they've probably been flown to you.

The authors note that:

"An entirely domestic food consumption scenario can reduce food-miles emissions by 0.27 GtCO₂e".

Since the authors estimated food system emissions to be 15.8 GtCO₂e, this reduction would be equal to 1.7%.

[0.27 / 15.8 * 100] = 1.7%.

https://ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions-from-transport

https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/global-co2-emissions-in-transport-by-mode-in-the-sustainable-development-scenario-2000-2070

The authors state the following:

"Compared with food-miles, which only contribute 18% to total freight-miles, we find that the food-miles emissions accounted for 27% (or 3.0 GtCO₂e) of total freight-miles emissions".

If 3 GtCO₂e is equal to 27% of total freight-mile emissions, then the authors must estimate that global freight emits 11.1 GtCO₂e.

[3 / 27 * 100] = 11.1 GtCO₂e

This is fantastic Hannah. Chapeau.

Your analysis is so accessible! Thank you for making data enjoyable. Your work is really powerful.