I was recently on Liv Boree’s podcast: Win-Win.

I’ve done a lot of interviews recently, but this one was a bit different (in a good way). Liv used to be a pro poker player (a World champion, I should add), and her podcast is about how competition manifests in the modern world. She takes on big questions – artificial intelligence, war, environmental problems – and tries to figure out how we turn win-lose situations into win-win ones.

The heart of her podcast is about the so-called “Moloch Trap”. A Moloch Trap is, in simple terms, a zero-sum game. It explains a situation where participants compete for object or outcome X but make something else worse in the process. Everyone competes for X, but in doing so, everyone ends up worse off.

It explains the situations with externalities or the preference for short-term gains at the sacrifice of the long-term future.

The problem is that it’s incredibly hard for any “player” to break the trap. If they do, they will lose out in the short term (and they might still be exposed to the downsides in the long term). Everyone is stuck in a “game” or “race” that they don’t want to be in, but it’s impossible to stop.

Some examples of the Moloch Trap

Maybe a few examples would help to explain it better. These are some I’ve heard Liv describe before.

1) Doping in sports. Lance Armstrong was stripped of his seven consecutive Tour de France titles in cycling after admitting he was using performance-enhancing drugs. We can point the finger, but the reality is that almost everyone (or at least everyone with a chance of placing highly) was doping in the sport at the time. Apparently, only 1 of the 21 podium-finishers over Armstrong’s stint at the top was not later implicated in the doping scandal (Fernando Escartin).

This was a classic Moloch trap. No one really wanted to have to take performance-enhancing drugs, not least because of the fear of getting caught. But it was almost impossible to do well without taking them because everyone else was.

2) Beauty filters on social media. People put filters on their pictures to make themselves look “nicer”. It’s then difficult for anyone to post without using a filter because it falls far short of the expectations set by everyone else. Instagram users end up in a race where images become increasingly distorted from reality, but no one really knows how to be the one to break the cycle.

3) Artificial intelligence (AI). There are lots of safety concerns about the speed at which AI is developing. Almost every tech leader – Sam Altman, Sundar Pichai, Mark Zuckerberg, to name a few – has said they are worried about AI risk. Yet it’s impossible for any of them to slow down. AI companies are now in a race, and if they put the brakes on while others keep accelerating, they will fall behind.

AI companies are now locked into a race that they all recognise is a major threat to humanity (also with lots of potential upside, I should add) but it’s in no one’s interest to be the one that lets up.

4) Nuclear weapons. Country X might want to live in a world free of nuclear weapons, but if Country Y and Z have them, it’s in their short-term interests to also have a deterrent and not leave themselves exposed.

Almost every environmental problem is a Moloch Trap

In my podcast episode with Liv, we focused on the environment.

The Moloch Trap explains almost every one of the world’s environmental problems. I struggled to think of one that doesn’t fall into this camp.

Environmental problems are caused by a fight for scarce resources, activities that push externalities and negative impacts onto others, and the sacrifice of long-term sustainability for short-term gains.

People overfish because they know that other fishermen are doing the same. If they don’t maximise their catch now, they’ll be left with none. This is not optimal for anyone in the medium to long term because the fish stocks will be depleted.

We cut down forests because there are economic gains – from using that land for something else, such as farming – to be made in the short term. If we don’t cut it down, then someone else probably will.

We burn fossil fuels because it offers us huge immediate benefits (energy) but at the expense of a stable climate in the medium-term. It’s in no single country’s interest to stop doing so because they will miss out on the short-term energy gains and will still have to deal with climate change if other countries keep polluting.

We deplete groundwater resources to irrigate our farms despite knowing that it will soon run out. If we don’t do it, someone else will, so we might as well make some money from what’s left while it’s still available.

Each of these is a classic “tragedy of the commons” situation.

The key question is how we can break the Moloch Trap and solve them?

How to break the Moloch Trap

By definition, Moloch Traps are incredibly hard to break. If it were easy, we’d be free of them already. Remember: players often recognise they’re in a race that doesn’t end well. They just don’t know how to get out of it.

The key is to get out of zero-sum games and scarcity mindsets. Turn win-lose situations into win-wins. Make it advantageous for people to forgo environmental damage.

That can come from a few places: better substitutes, coordination, policy and social stigma.

First, by finding substitutes that provide the same short-term benefits, without the long-term damage. It’s energy that countries want, not fossil fuels. Innovate cheap and better alternatives, and they’ll make the switch. Better yet, build alternatives with even more short-term economic benefits, and you’ll have a win-win situation.

What won’t work is expecting countries to give up the benefits of energy entirely. If there’s no substitute, it won’t happen.

China is installing clean energy at breakneck speed domestically but also manufacturing solar power and batteries to sell to other countries. Why? Because there are real short-term economic incentives to do so. Some analysts suggest that clean energy was its biggest driver of economic growth last year.

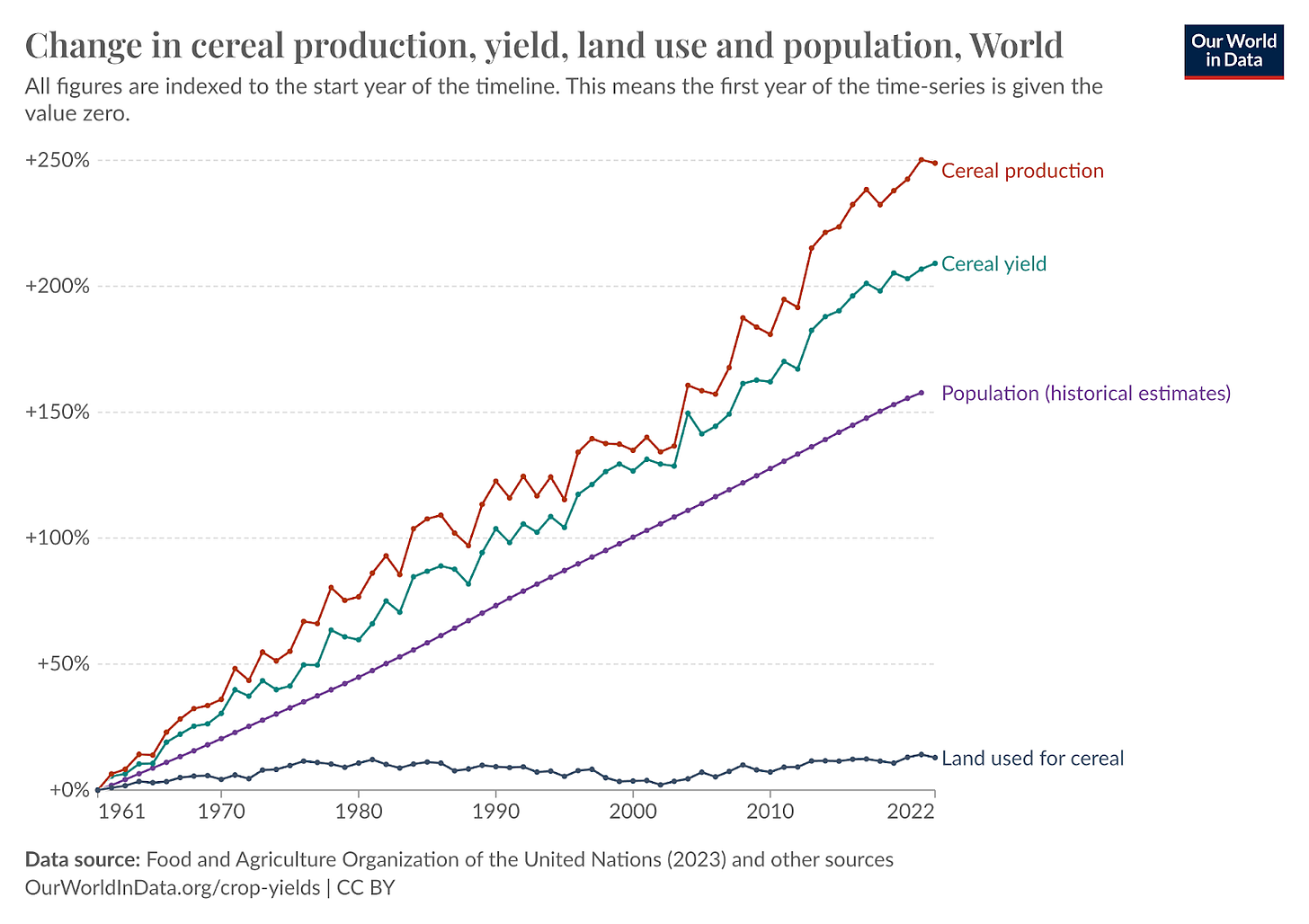

You can see examples of this in other areas, too. One way to limit deforestation and habitat loss is to improve agricultural productivity. More food from less land. You might argue that this gives them even more incentive to cut down forests because they’ll be able to produce even more crops on that land. There are certainly situations where that’s true. But it’s not always the case: if the market is close to being saturated, oversupply will simply push down prices and it might not be that economically advantageous at all.

The amount of wild fish caught each year has barely increased over the last decade despite increased seafood demand. That’s because of the rise of aquaculture, where fish farmers quite literally grow their own. It’s no longer a zero-sum game.

The same was true in the transition from hunting to agriculture. Hunting is a zero-sum game: there is a finite amount of wild animals to catch. Agriculture is not (unless you’re close to the limits of land availability, which the first farmers certainly weren’t) if you can increase crop yields and grow more from less.

Policy can also drive short-term incentives for good substitutes or needs to step in in their absence.

Aquaculture has been a bit of a saving grace for wild fisheries. But strict limits on fish catch have also been crucial in restoring depleted populations. Well-managed fish stocks are monitored closely; scientists calculate how much can be caught while maintaining optimal population levels; and quotas are handed out to fishermen for how much they can catch. There are severe penalties for breaking the limit.

Logging activity is closely monitored in the Brazilian Amazon, and there are harsh consequences for those caught deforesting illegally. Here, the stringency of policy and law enforcement matters – see the ups and downs in deforestation rates between presidencies (I wrote about this in more detail here).

National policies and regulations have had a significant impact on levels of air pollution, too. The Clean Air Act in countries such as the US and the UK have led to massive reductions in pollution.

The final component, I think, is social attitudes or stigma. In the example of beauty filters: if there were some strong social penalty for using a filter in the first place, the norms of Instagram posting would shift significantly. If it was collectively recognised that filters and photoshop were pushing these apps to an equilibrium that no one wanted, there could eventually be widespread pushback.

We can see examples of this in environmentalism and conservation. Animal poaching has been a continuing problem in many parts of the world. Rhino horns, elephant tusks, and gorilla hands can make someone a lot of money. How can some of the poorest countries in the world stop this from happening? Make the economic benefits of wildlife tourism to the local community very clear.

This transforms poaching from zero-sum game – I should get the horns and tusks before my neighbours do – into a positive-sum game. If we, as a community, protect our wildlife then we all reap the economic benefits (and in a relatively short timeframe). Kenya has managed to do this extremely well: its illegal ivory trade has shrunk in recent decades, while many other countries have struggled. A crucial ingredient of success has been cooperation between rangers, prosecutors and investigators. There is both a strong financial penalty for poaching and a social stigma: when someone kills an animal, they are essentially stealing money from the wider community. It’s in everyone’s short-term interests to maintain a strong tourism industry.

Breaking Moloch Traps often need multiple approaches

There’s rarely just a single instrument that breaks a Moloch Trap. Often, you need some combination of all of the above.

It’s difficult for governments to implement policies when there are no good substitutes to move to. It would be unthinkable for them to ban the sale of new petrol and diesel cars if there were no good substitutes in the form of electric ones. They can’t make fossil fuels really expensive without viable alternatives in the form of cheap renewables or nuclear.

Imagine a government imposing harsh penalties on deforestation when food supplies are scarce and farmers have no way of increasing agricultural productivity.

It’s also easier to implement policies when there is social pressure or stigma.

What’s key to breaking the Moloch Trap is turning zero-sum games into positive-sum ones. I think this is underrated in environmental discussions. I often see people pushing for solutions that are, inevitably, zero-sum. That won’t win widespread public support and definitely won’t allow it to be sustained for decades.

The good news is that I think we’re in a unique position today to generate more positive sum games than ever before. In the past, energy and agriculture were zero-sum games. There really was no way to increase agricultural productivity: yields were low and constant for thousands of years. There was really no way to make energy without burning stuff: either wood or fossil fuels. Technological innovation is what allows us to break out of these win-lose games. That’s the opportunity we have, and it’s up to us to use these innovations responsibly.

Technology won’t do it on its own: it relies on a social, political and economic ecosystem around it to guide it towards the outcomes we want.

When focusing on environmental solutions, be on the lookout for win-wins. Switching from one win-lose to another is not going to get us there.

Check out Liv Boeree’s podcast:

This is a fine article, but why introduce Moloch Traps to refer to collective action problems? These are well studied in game theory, especially from the 1960s onwards, and often attributed to Garrett Hardin and then Elinor Ostrom (who took at different view to the causes and solutions). Of course there's a longer history.

Could we get more detail on the etymology of Moloch Traps? And how they differ, at all?

Otherwise I fear this is a layer of jargon. When Goggling the term I can only see Liv Boeree applying it, which isn't a great sign/

"It’s energy that countries want, not fossil fuels."

I'm gonna quibble with this and say it's not even energy that we want. It's hot showers and cold beer and comfort and mobility, as Amory Lovins famously said. So the substitute for fossil fuels needn't always be an energy source. It might be insulation or opening a window or better urban design.