The world has (probably) passed peak pollution

Millions die prematurely from local air pollution, but we can reduce this number significantly.

The health impacts of air pollution are often underrated. There are a range of estimates for how many people die prematurely from local air pollution every year.1 All are in the low millions. The World Health Organization estimates around 7 million.

The good news, then, is that the world is probably passed “peak pollution”. I say “probably” because confidently declaring a peak is, apparently, the best way to make sure it doesn’t happen.

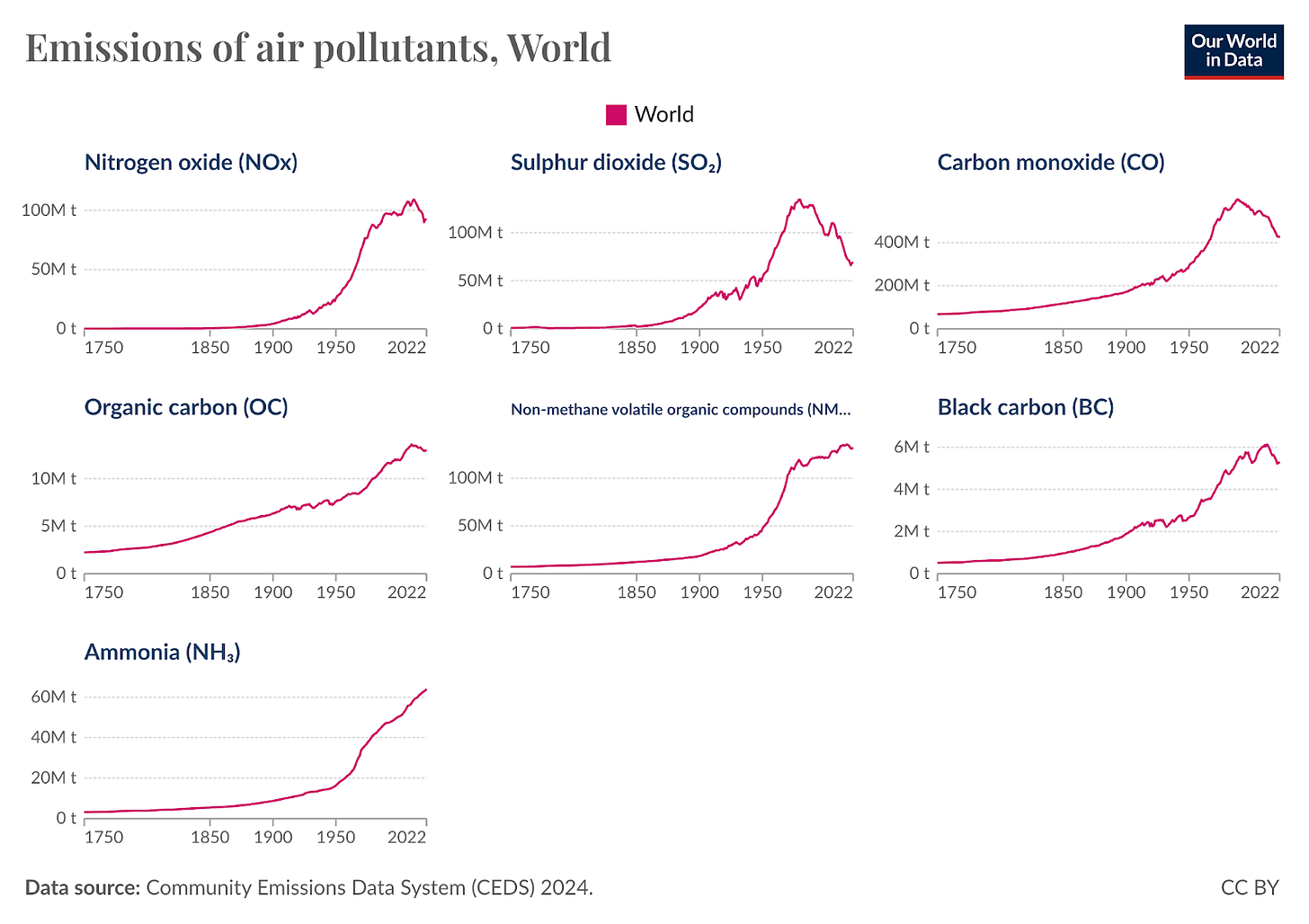

Here, I’m talking specifically about emissions of harmful local air pollutants: gases like nitrogen oxides (NOx), sulphur dioxide which causes acid rain, carbon monoxide, black carbon, organic carbon, non-methane volatile organic compounds. I’m not talking about greenhouse gases.

The Community Emissions Data System (CEDS) recently extended its long-term dataset on emissions of air pollutants up to the end of 2022.

I updated this data in our explorer tool on Our World in Data (where you can explore the trends by country).

What’s striking is that emissions appear to have peaked for all of these pollutants, with the exception of ammonia, which is almost entirely produced by agriculture. Organic carbon and NMVOCs are not quite out of the clear yet, but might not reach their previous peaks again.

Of course, emissions are not falling everywhere. They’ve fallen steeply in richer countries like the US and much of Europe. And the big turning point for the global figures has been the rapid turnaround in China. Emissions have declined rapidly in the last decade, with huge gains for public health.

It’s in low and lower-middle income countries where emissions are still rising, and pollution levels in cities are the highest. This is not surprising: air pollution is one of the few areas where the “Environmental Kuznets Curve” tells a pretty accurate and consistent story.

Air pollution increases as countries develop, gain access to energy, and industrialise. They then fall once a country gets rich enough to impose pollution standards and limits without infringing on development and the move away from energy poverty.

The goal now is to see if countries can move through this curve much faster – and with lower levels of pollution – than countries like the US or the UK did. This should be doable: we’ve learned a lot over the last 50 years about how to produce energy with less pollution, what technologies work and don’t work, and have reduced the costs of solutions that were expensive in their early days.

Note that this is not a finger-pointing exercise where rich countries tell poorer ones not to pollute. We’re mostly talking about local air pollution. The negative impacts of pollution are felt by domestic populations. It’s about how we ensure that the poorest countries can gain access to energy, alleviate poverty, and develop while limiting the number of people who die prematurely from air pollution in the process.

These are measured as premature deaths. Most are not 20-year-olds dying from respiratory diseases or asthma (although childhood asthma is one symptom of local air pollution) but older people dying months or years earlier than they would have in the absence of pollution.

In highly polluted cities, these “years lost” can be up to 5 years or so.

Thanks so very much, Hannah. One of your most important contributions is to remind people of what is facing billions of humans right now, and what we can and are doing about it, rather than spreading the Gospel of Doom about the future (and helping put TFG back in power)

Thank you so much. That's very insightful and makes me hopeful. I am wondering: do you know if the reductions in richer countries are really caused by more efficiency / better technologies or might have anything to do with outsourcing or with changing to technologies that cause harm in other areas (e.g. land use)?