Under-the-hood of writing on Substack

Subscribers, revenue, and why more people should write long-form.

It has been around two and a half years since I started writing on Substack. I’ve sent out a newsletter every one to two weeks.

It’s been fun. I get to think about questions that I have or know others have, rummage around in the numbers for the answer, then try to make sense of it on paper.

I’m often asked why I have my own Substack when I publish articles on Our World in Data (my actual job). Two main reasons.

First, you’ll often find me doing rough back-of-the-envelope stuff here to try to get some sense of magnitude. Some of those less rigorous, more experimental projects wouldn’t meet the quality criteria for what goes on Our World in Data but I still think they’re valuable to share somewhere less formal.

Second, publishing things that are “evergreen” is a key priority for the work we do at OWID. Our focus is often on the longer-term trends, not what happened yesterday. We don’t write articles about the latest debate or news story that will be out-of-date in a week. But sometimes I do have something to say about what’s going on right now, and having my own Substack gives me a place to weigh in on these shorter-term discussion cycles.

My sense is that information and media environments have changed quite a lot recently. And I have little doubt that — especially with AI — they will continue to do so. Previously people followed large institutions; that’s where they got all of their news and opinions. Now, more people are following individuals, or rather, a collection of hand-picked individuals.

That has opened up opportunities for people to build an audience on their own. It’s similar to the way that cable TV is being replaced by YouTube, podcasts and streaming.

But like YouTube, it’s hard for people who don’t have experience with Substack to know what it’s actually like “under-the-hood”. They see people writing on here, but have no idea how many people read their stuff, or if they could actually do it as a job.

I think transparency on these numbers and trends is helpful. I only have my own data and experience to go with, but hopefully by sharing them openly it gives people who are potentially interested in writing some useful context.

Almost no one has an audience to start with; to build one, you need to publish interesting things consistently

First, some basic stats on subscribers and readership.

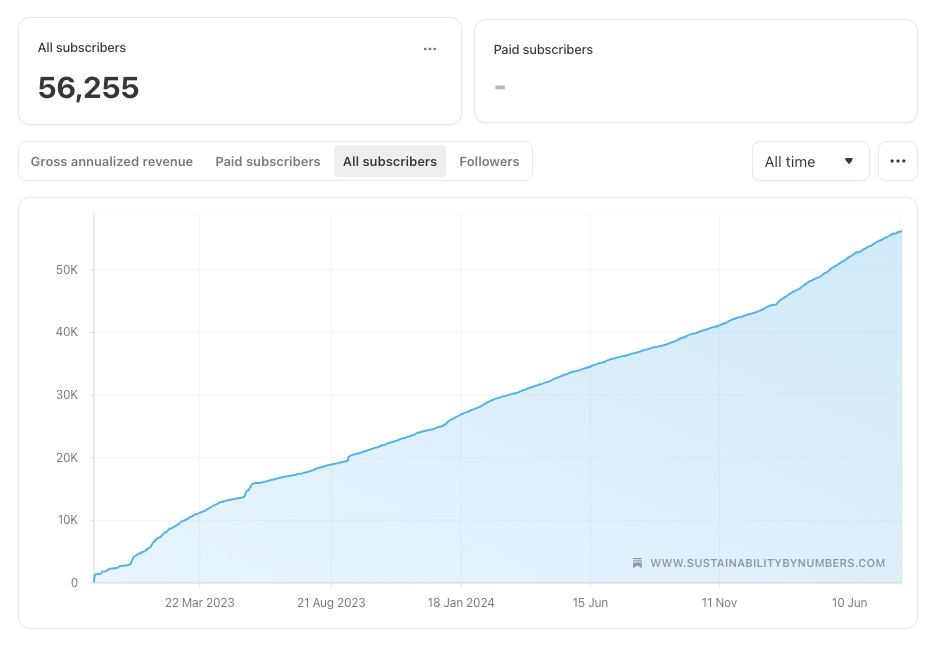

I have a little over 56,000 subscribers.

Not all of them open every email; actually, only around half do (that half depends on the topic). But lots of people who are not subscribed also read these posts, so the number of reads typically varies from around 50,000 to 120,000 per article.

When I speak to people who have ideas they want to share themselves and I start probing on why they don’t have a newsletter (or other medium — video, podcast, whatever suits them best), the standard reply is that “they don’t have an audience interested in what they have to say”. In other words, what’s the point of writing if no one reads it?

I have a much longer answer to that, which is that writing is still valuable to refine and interrogate ideas, even if no one sees it. But more importantly, almost no one has an audience when they start writing! Do you think I just launched a newsletter and had 50,000 readers immediately?

Sure, there are some well-known writers whose readership followed them over from elsewhere. Paul Krugman (who previously won the Nobel Prize in Economics) recently quit his column at the New York Times, taking his many fans with him to Substack. He quickly amassed almost 400,000 subscribers. But these people are rare. And even then, they also started from zero at the beginning of their writing careers.

Look below at the chart of my subscriber growth over the past 2.5 years. As someone who loves S-curves, it’s an annoyingly straight line. Sure, there are some slightly larger hops and gradients along the way, but for the most part, I’ve gained a pretty regular number of subscribers by consistently publishing week after week.

If you have something to say, you need to get used to the fact that hardly anyone reads your work (or watches your video, or listens to your podcast) at the beginning. But post semi-interesting things consistently, and people will follow along. Sorry, but there is no substitute for putting in the effort again and again and again.

You’ll notice in the chart below that there is no value for “Paid subscribers”. This is because I haven’t turned on payments, as I’ll come on to.

Can you make a living on Substack?

I guess this part is what is most obscure (and therefore revealing) to many.

When people subscribe to your newsletter, they can pledge a financial contribution. These come in various forms, such as a monthly or annual subscription, and at different levels. Often, writers have tiered systems, so many posts are only available when people sign up for a paid subscription.

Writers can keep these payments “turned off”, which means they don’t receive anything, and nothing comes out of the pledgers’ bank accounts. I have not turned payments on, so I haven’t received any money for my Substack writing. Everything is free.

There are two key reasons for this. First, I have a full-time job, and a secure income. Substack is just a fun side-project for me, and it doesn’t feel right to monetise it. I like writing on the internet for free, and don’t want people to be limited by the fact that they can’t pay. To be clear: I think it’s fine and great that others make money from Substack. Some now do it as their full-time job, and therefore should be paid for it. That’s just not my circumstances, and keeping things free works for me.

The second reason is that I like the freedom of writing on my own schedule and picking what I want to write about. I try to publish here regularly, but I also have a full-time job, write books, host a podcast, do media interviews, and (sometimes) write academic papers. Finding the time to think through a question properly, run the numbers (without making mistakes), and write it up here can be stressful. If people were paying for this newsletter, I’d feel even more pressure to publish every week, even when I don’t have the time. Quite rightly: you can’t have people paying, then fail to deliver.

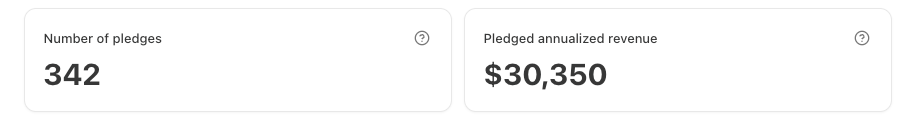

Anyway, despite not accepting payments, people are very generous and do make pledges. Thank you very much to anyone who has done that (I appreciate the sentiment, even if I don’t take the money). As you can see below, if I were to open them, I’d make about $30,000 a year.

That gives you a sense of how subscriber counts translate into revenue. 56,000 subscribers come to around $30,000.

Now these numbers are quite pessimistic. I never ask anyone to pay. I don’t advertise it. If I’m honest, I don’t try very hard to promote the newsletter. Most of the reach has come organically. If I were to take this growth seriously and treat it like a full-time job, I’m confident I could get that number to around $50,000 within six months.

So, can you make a living from Substack? Those with larger followings clearly do. It’s their job, and I’m sure they live pretty well. Mid-level Substackers or those just starting out will struggle to have it as their only income (although it could be a nice supplement).

Another way to think of it is akin to Kevin Kelly’s “1000 true fans”. If you develop a real niche where even just 1000 people really love what you do, then it’s possible. Let’s say they each pay $5 a month. That’s $60 a year each, and $60,000 in total.

So, you don’t need hundreds of thousands of followers to make a living. But you either need many tens of thousands of fairly interested subscribers or a smaller number of very invested ones. I’d say that those making a living on Substack are in the small minority, but it’s clearly not impossible.

If you want to publish on the internet, grow a thick skin

If you’re going to put yourself out there, then expect people to be mean to you. It’s the internet.

The bigger your audience, the thicker the skin you need. Thankfully the time it takes to build that readership gives you time to grow it.

I won’t pretend that people hurling insults into your inbox doesn’t ever still sting. But I’m much less bothered by it than I used to be.

Why I think more people should do long-form writing

If you do have some tolerance for criticism and have ideas to share, I’d tell you to consider doing longer-form writing. By “longer-form” I just mean more than social media posts or comments; 1,000 to 2,000 words that lets you craft a narrative and explain your thoughts with nuance.

People have the impression that online media environments are saturated, and there’s not room for someone else. I don’t think that’s true. When I come to tackle a question on Substack, I often expect there are 1000 findable, clear articles that have already done it. Often there’s not a single one (at least tackling the question in the way that I would want to do so).

I hear so many people with expertise (or just thoughtful insight) on a topic grumble something like “what people don’t understand is that …”. Well, has anyone published a very clear explainer on what the misunderstanding is? If the answer is no, why would you expect any different? Rather than torturing yourself about the world’s ignorance, maybe you should be the one who takes the time to communicate it properly.

I say this as someone who hangs around with academics a lot. They do incredibly valuable research but then don’t take the time to explain it beyond the other 10 experts in their field. Then they get annoyed that public discussion about their discipline is so bad.

Now despite writing and publishing a lot, I still get frustrated by how bad public discussion is, so this is not a magical cure. But at least it lets you curate a small corner of the internet where people can have better conversations. And very occasionally, those insights make it out into the mainstream. They never will, though, if you’re not willing to put those ideas out there in the first place.

I create an environmental comic strip (Arctic Circle) and normally read your work for your exceptionally good climate change data analysis.

As someone whose income has been eroded by the Internet (making cartoons effectively free) and AI (using our cartoons to train generative AI which is now taking our work), I found this post particularly pertinent. As well as supplementing my income, writing on Substack has built my community and forged connections between me, readers and other cartoonists.

You should consider enabling payments, even if you take the money and donate it to a cause you believe in. Margaret Atwood has done that (I think her cause is a bird charity). Payments support a platform that supports artists. Substack has its problems, but they aren’t nearly as bad as other corners of the Internet and as it grows, it will need money to improve the platform for artists and writers like me.

Thank you for what you do.

I wish people will take your advice on growing a thick skin and become more tolerant to criticism. Today, it is unfortunately a common practice for quite a lot of people to simply block anyone who dares to make a critical comment of their work, creating thus a bubble of admirers.

Growing a thick skin and not taking criticism personally is beneficial, first and foremost, for the development of the writer/researcher themselves.