Can we break the human development-environment trade-off?

The opportunity to build a human-nature relationship that is not zero-sum.

A few years ago, I gave a TED Talk, titled “Are We the Last Generation — or the First Sustainable One?”. It was a brief summary of my first book, Not the End of the World. The original book title was actually The First Generation, and that’s what I assumed would be on the front cover throughout the entire writing process. We changed it quite late on, and I think we made the right choice in the end.

But I still believe in the “first generation” concept, and since then, people have asked me to summarise it in the form of an article (rather than a talk or a book). So, here it is, written in brief.

My argument is simple: for the first time in history, we can improve human wellbeing while reducing our environmental impact.

It’s common to think that sustainability — or, rather, our lack of sustainability — is a new problem. For most of human history, our ancestors lived sustainably, and only recently has that been knocked off-balance.

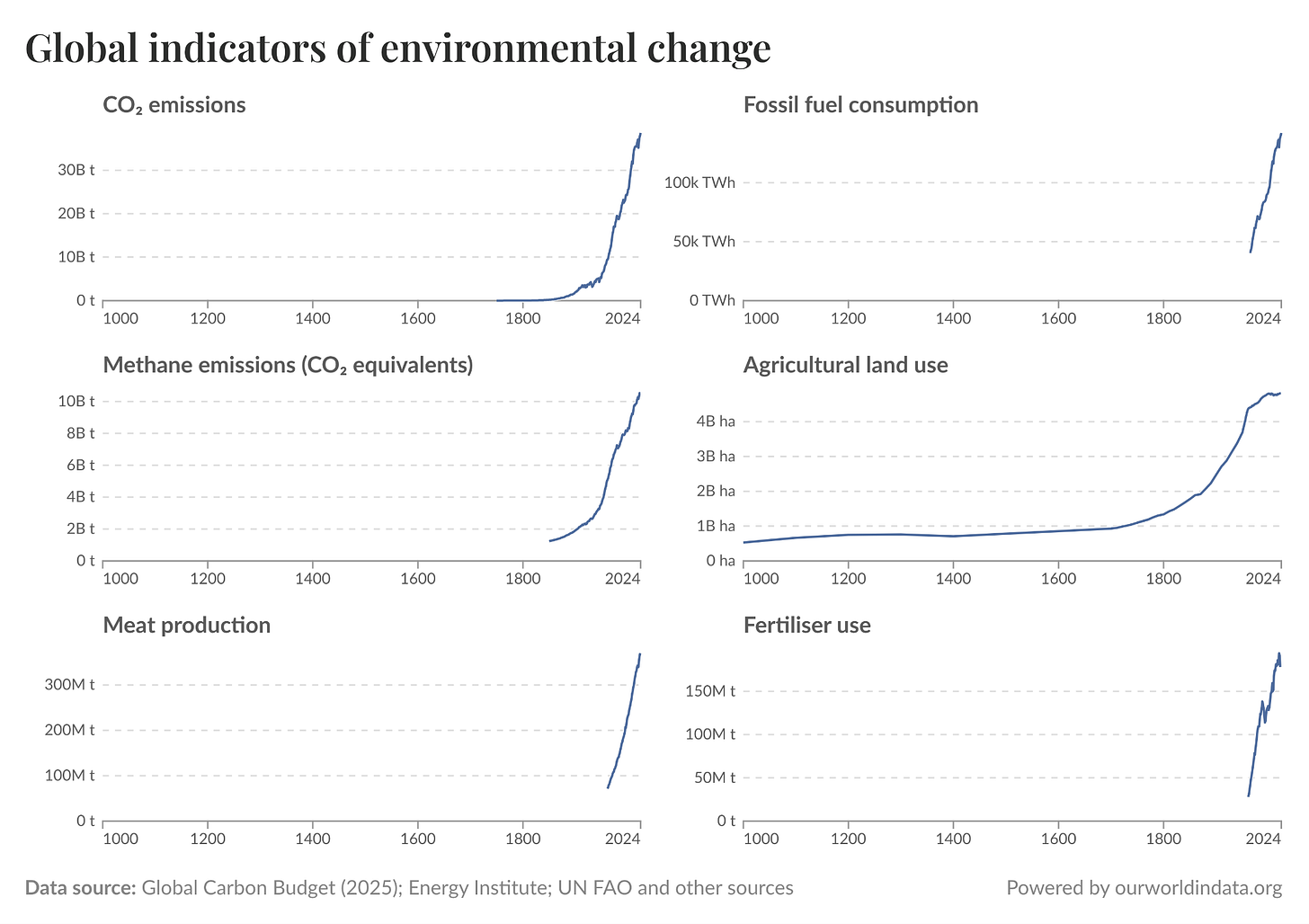

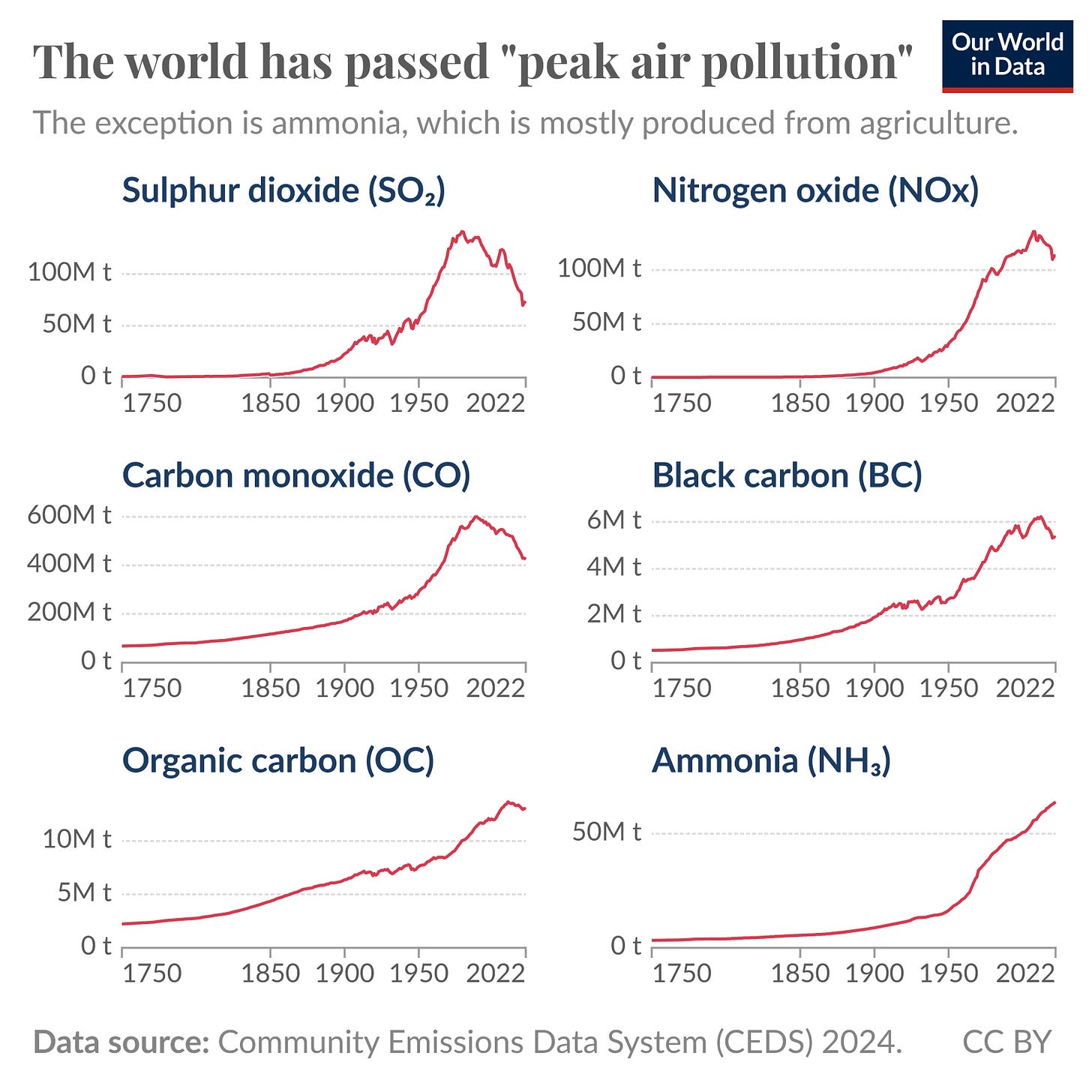

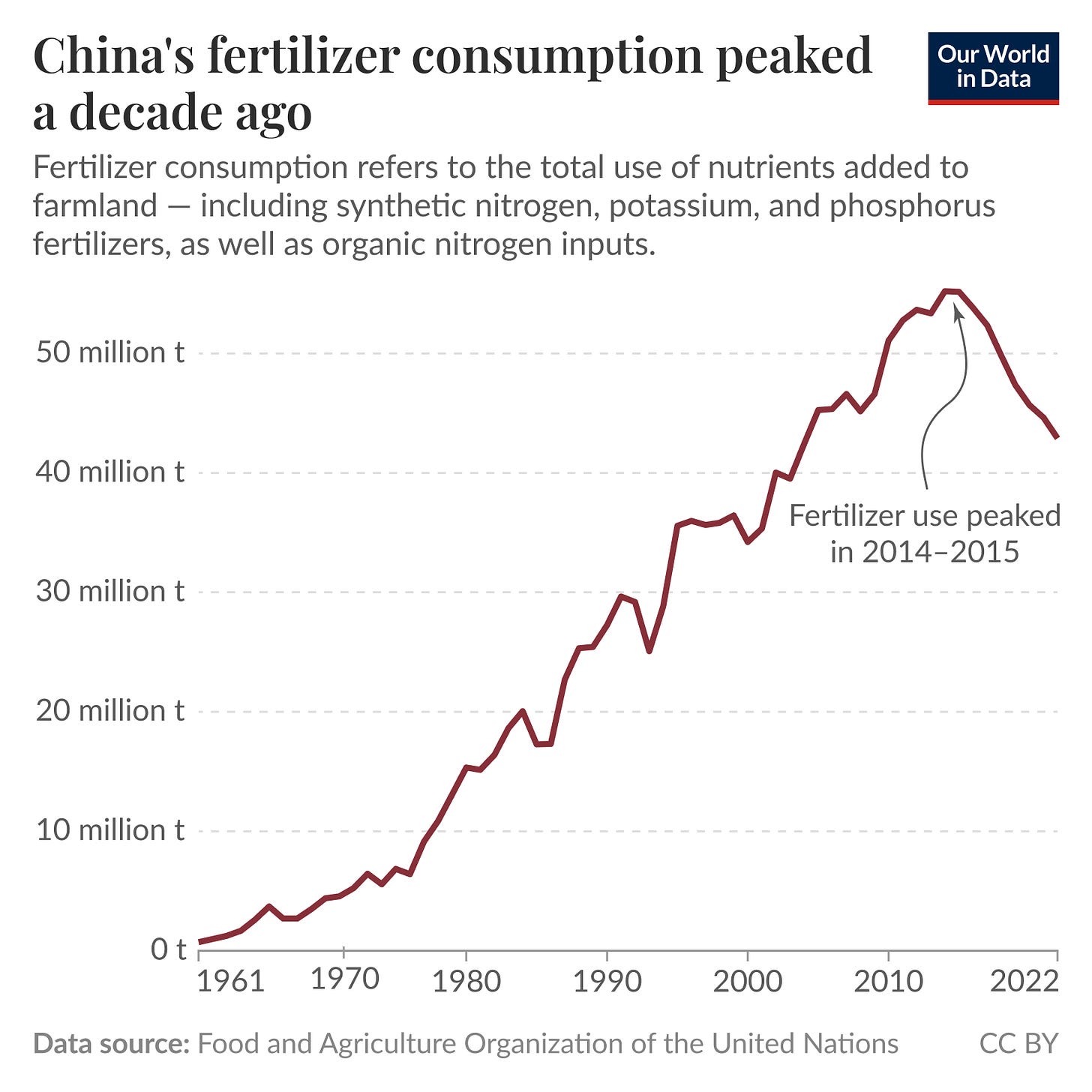

Coming from an environmental background, I would have said the same. Look at any series of graphs on environmental pressure, and it’s not hard to see why people would frame it as a new problem. Plot global curves of carbon dioxide emissions, land use, air pollution, global temperatures, or fertiliser use, and they all rise sharply in the last century. It creates the impression that things were fine, but now they’re really not. It’s these curves that often make people — especially young people — feel fatalistic about the future. I was certainly one of them.

By this definition of environmental pressure, it is true that the world has become much less sustainable in modern history. But that only captures half of the story.

To me, sustainability means more than that. Yes, I care deeply about the environment: to protect opportunities for future human generations that come after us, but also to preserve a liveable world for other species and ecosystems. But I also care about the billions of people who are alive today. I want them to be able to live a good life; healthy, well-fed, poverty-free, content, and with opportunities to flourish in whatever way they wish.

That means our “sustainability equation” has two halves1:

By this broader definition, humans have never been truly sustainable. Yes, many generations of our ancestors had a lower environmental impact than we do today. But by many basic metrics of human wellbeing, life was not good.

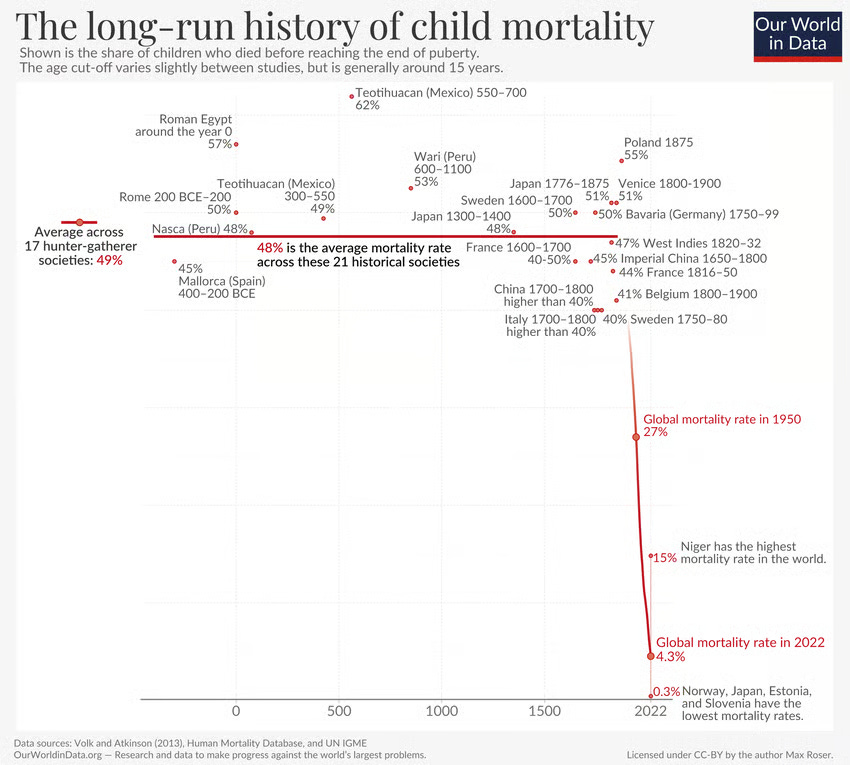

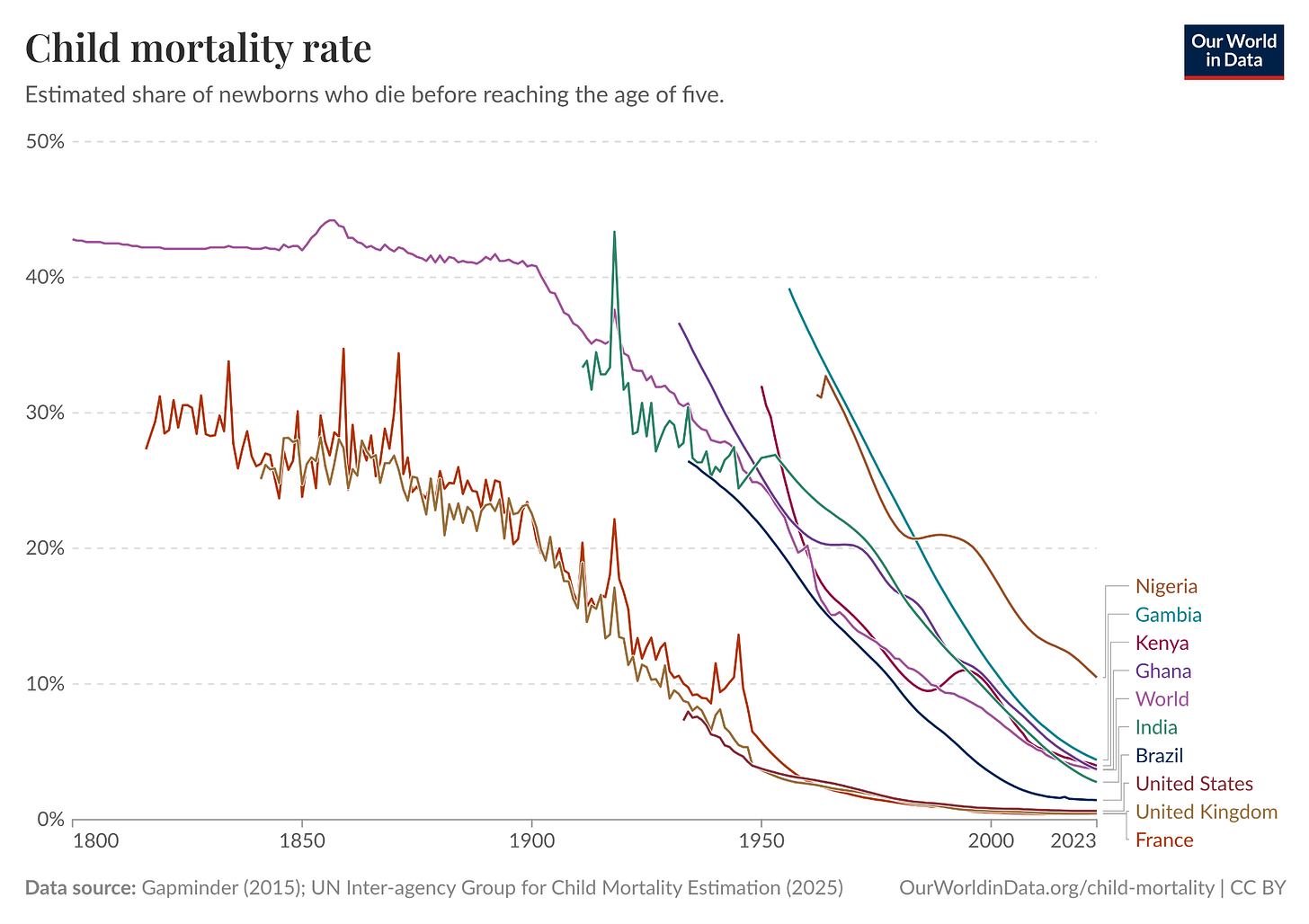

The most stark is child mortality. For most of human history, a newborn’s odds of surviving to puberty were a coin toss. Half of children died. If a family had six children, they might have to bury three of them. This was true across many time periods and locations: from Roman Egypt and Ancient Rome, to Imperial China and Medieval Japan.2 Data is more scarce for historical hunter-gatherer societies, so most of these estimates come from modern-day ones. The study did have evidence from one Palaeolithic society at the famous Indian Knoll archaeological site, dating back to around 2,500 BCE.3 In both modern and ancient hunter-gatherer societies, the rate was also close to 50%.

But over the last few centuries, humans have achieved the seemingly impossible: we’ve reduced these rates dramatically. As you can see in the chart, the deadlock breaks, and rates have since plummeted to 4%.

As I’ll come to, the world today is still tragically unequal. But it’s not true that this progress has only happened in some rich countries. Falling child mortality has happened everywhere. Take a look at the chart below [here’s the interactive data]. A baby born in Nigeria is more than 20-times more likely to die in childhood than one born in Britain. It is among the countries with the highest child mortality rates. Nonetheless, rates have fallen from over one-third to 10% within decades. In Gambia, rates have fallen dramatically from 40% to 5%. In post-colonial India, from 30% to 3%.

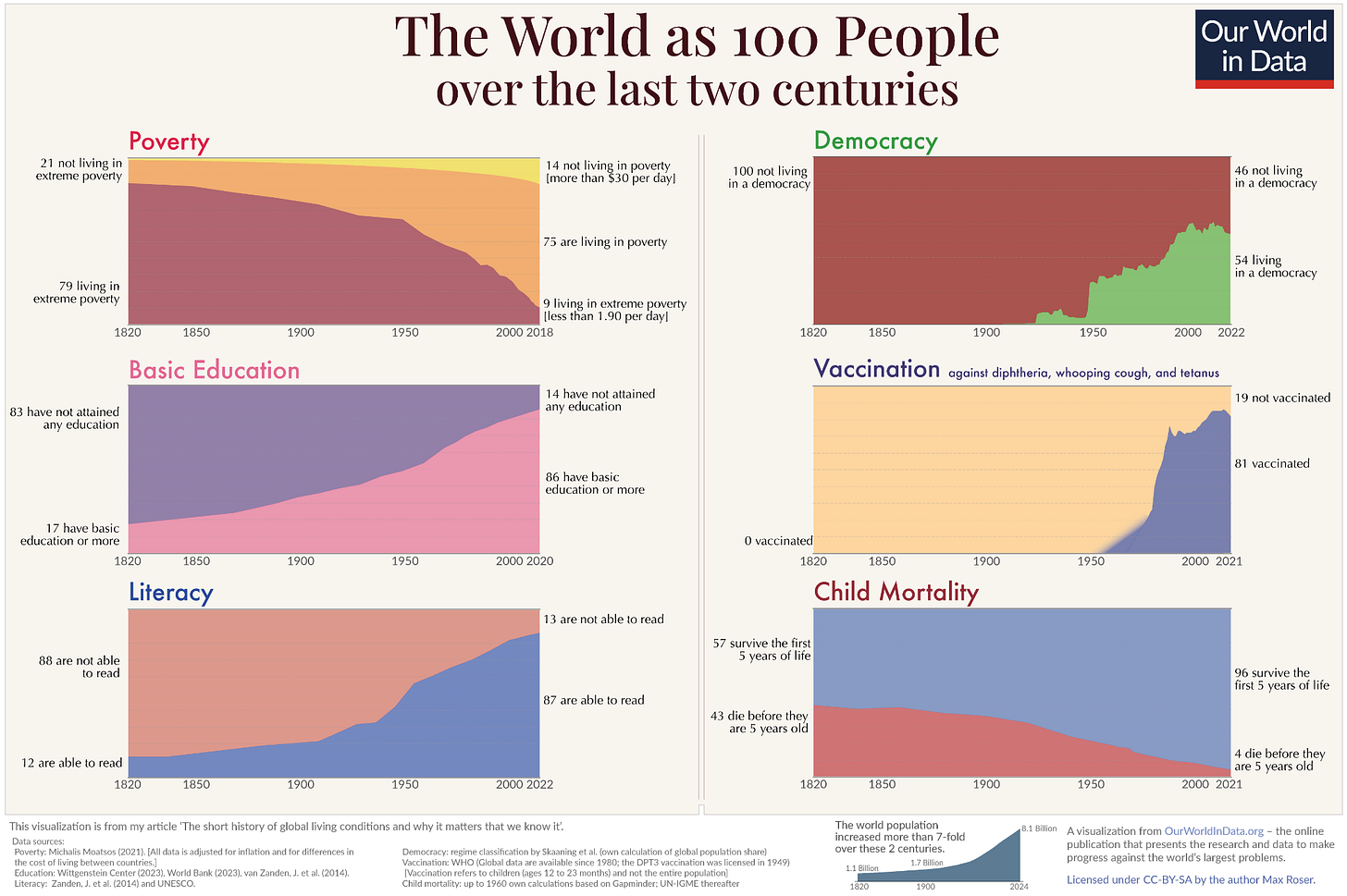

What’s true for child mortality is true for most other human development metrics. The odds that a woman dies in childbirth have plummeted. Global maternal mortality rates have more than halved since 1980. So, too, have the total number of women dying in childbirth. Some of the most dramatic declines have been in the world’s poorest countries; rates in Sierra Leone, for example, have fallen by more than 75% since 2000. Extreme poverty rates — defined by an extremely low poverty line of just $3 per day — have fallen from 75% to 10%. This is also true for those living under higher poverty lines. Across the world, most children get vaccinated against terrible diseases. Most have the opportunity to go to school and get an education. People are living longer than ever. Life satisfaction and happiness have increased (and tend to be higher in richer countries). The list goes on.

Even deaths from disasters have declined over the last century despite climate change, thanks to improvements in weather forecasting; early warning systems; earthquake- and flood-proof infrastructure; emergency response; and other developments that have made societies more resilient.

What I hope people take away from this article is that humans are capable of solving problems. Really big ones that would have seemed unsolvable to those who came before us. We are a flawed species that makes mistakes, but we are not hopeless.

A lot of this human progress was achieved at the cost of the environment

To get back to my earlier equation of sustainability: humans made a lot of progress on the first half (improving current living standards) but at the cost of the second half (preserving the environment for future generations, and other species).

Energy lay at the heart of much of this human progress. That energy mostly came from fossil fuels. Of course, that comes at the cost of more greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution.

The world made huge strides in global food production, which outpaced rapid population growth, despite many people’s fears that the world was on the brink of widespread famine. But this came at a huge cost for biodiversity and ecosystems. Half of the world’s habitable land is now used for farming. It’s the leading driver of deforestation (and always has been), biodiversity loss, freshwater use, and water pollution.

Follow the many curves of environmental impact, and they closely follow the curves of human development. The historical trade-off is clear.

While it’s broadly true that human societies in the more distant past had a much lower environmental impact — and therefore did far better on the second half of the equation — their impacts weren’t zero.

Air pollution is a problem that predates the Industrial Revolution. We generate pollution whenever we burn stuff, and without fossil fuels, people burn wood and biomass. Billions living on lower incomes still rely on biomass (killing millions each year, as a result). This was incredibly bad for people’s health. Researchers have found damaged tissue in the lungs of Egyptian Mummies and hunter-gatherers; evidence that they were breathing in polluted air.4 Pollution is not just a post-industrial problem.

Biodiversity loss is not a modern problem either. Rates have certainly accelerated in the last few centuries, but human impacts on animal populations and extinctions are not new. Around 50,000 to 10,000 years ago, many of the world’s largest mammal species went extinct. This is known as the “Quaternary Megafauna Extinction”. While the exact causes are still debated, it seems likely that humans played a key role in driving these extinctions. Look at when humans arrived on different continents, and you’ll find a wave of mammal extinctions not far behind. That’s despite the fact that there were probably only 5 to 10 million people in the world at the time.

Still, I think it’s fair to say that, overall, our ancestors had a lower environmental impact than we’ve had in recent history. At least in aggregate. But again, this failed to meet the definition of sustainability that I’m using. Environmental impacts might have been low, but child died in huge numbers, as did their mothers; life expectancy was low, and food supplies often fraught.

We are in a unique position to improve human wellbeing while reducing our environmental impact at the same time

If sustainability were measured by a set of scales, for a long time they were tilted in one direction, and in the last few centuries they’ve dramatically tipped in the other. There were inherent trade-offs between human development and environmental degradation.

The question is whether we can break this. I think we can, and that is why I say we have the opportunity to become one of the first “sustainable” generations. We can improve human standards of living while reducing our environmental impacts.

There are already signs that this is happening. That’s largely because we’ve developed alternative technologies that have a much lower impact.5

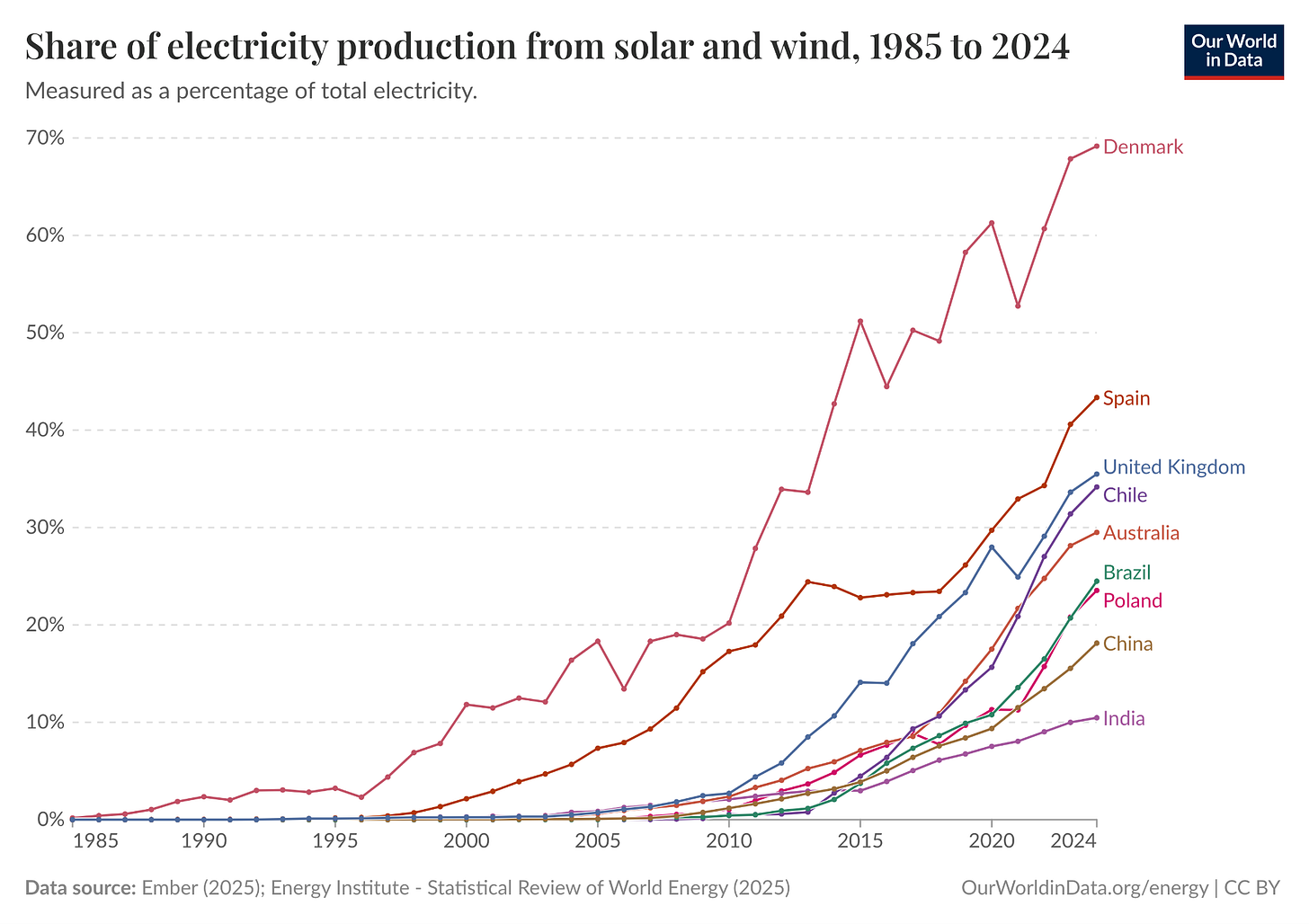

Energy services have been — and still are — a key driver of human development. But historically, they almost always come from burning stuff: either biomass or fossil fuels. There were really no affordable or scalable alternatives until very recently. First, with nuclear and hydropower, and in just the last five to ten years, with cheap solar and wind.

Again, if these alternatives were much more expensive than fossil fuels, then that trade-off would still exist: countries would need to choose between the short-term goals of lifting people out of energy poverty and maintaining high standards of living, and medium-to-long-term goals of tackling climate change and air pollution. The rapid drop in renewable energy costs in the last decade (alongside huge improvements in battery technologies) has started to break this deadlock. Affordable energy can now also be clean.6

As you can see below, solar and wind technologies are being rapidly deployed. And, increasingly, some of the world’s poorest countries, where energy poverty rates are still extremely high.7

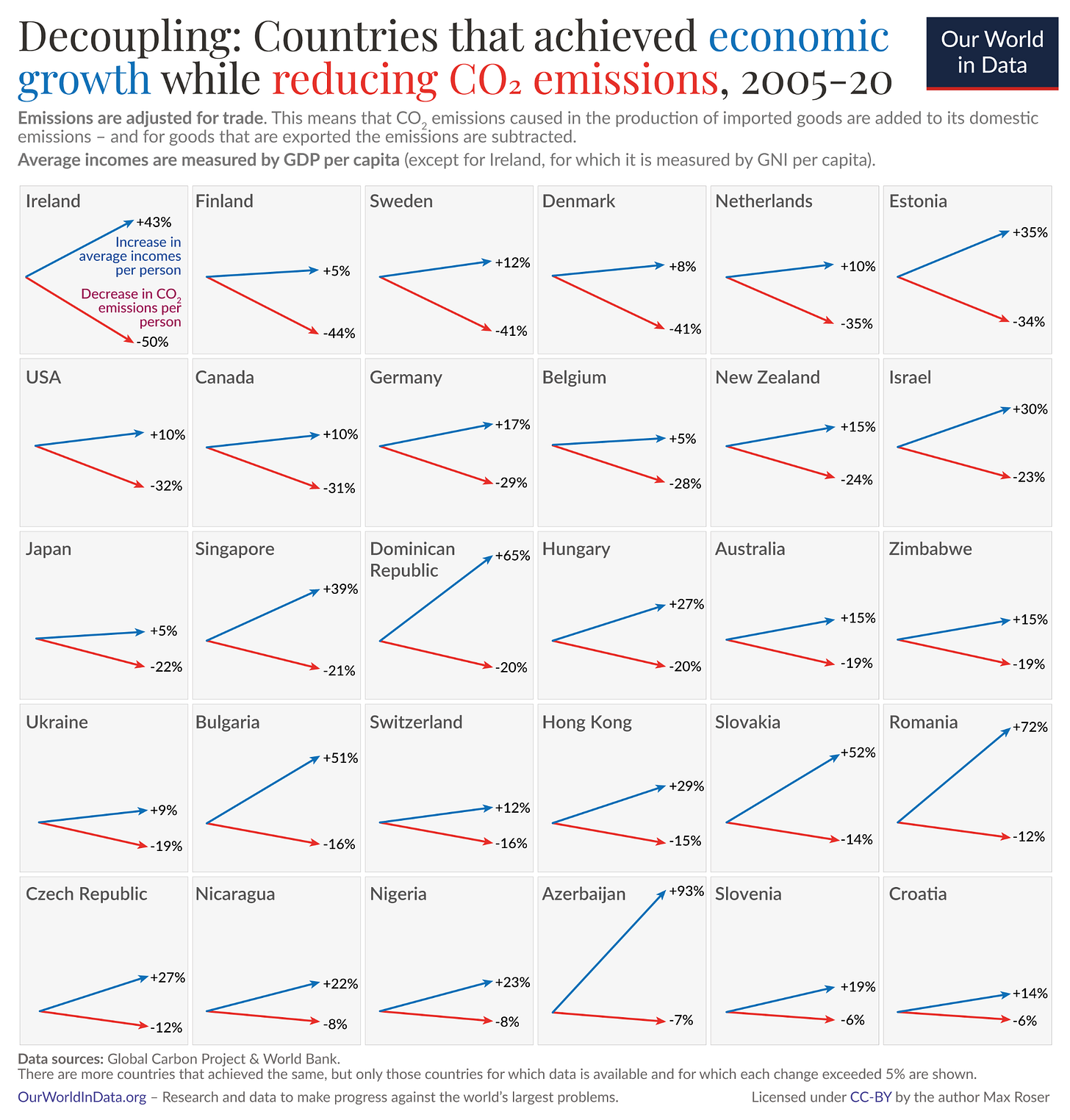

As a result, many countries have managed to grow their economies, while reducing their emissions.

Remember the big hole we made in the ozone layer? We’ve basically fixed that. Or acid rain across Europe and North America? We don’t hear much about that anymore either.

Local air pollution is still a huge problem globally, with millions dying prematurely every year because of it. But the world has now passed “peak air pollution”, and in many countries, people are breathing the cleanest air in a long time. If you want to see how quickly this can happen, look at China: its levels of air pollution dropped by two-thirds within a decade. That’s estimated to have added several years of life expectancy to people living in cities like Beijing.

Agricultural innovation and improvements in crop yields mean we can grow more food on less land. A lot of these gains had been driven by the use (and often, overuse) of fertilisers and pesticides, which create their own environmental problems. But, again, the data shows us that this trade-off can weaken. Global fertiliser use has been levelling off in recent years, and many countries have managed to increase yields while using fewer agrichemical inputs. This has been more prominent in the European Union, particularly through its “Farm to Fork” and pollution strategies. China’s policies have also put it past the peak of fertiliser and pesticide use. Our ability to use inputs more effectively will only increase with precision technologies that can work out where nutrients are needed, and where they will be wasted.

The other big driver of environmental degradation has been the world’s growing appetite for animal products. These tend to use more land, generate more greenhouse gases, use more water, and generate more water pollution than plant-based foods. The diversification of diets — which includes higher consumption of meat and dairy — is often associated with improvements in nutrition. People transition from a monotonous diet of staple crops to one that is more varied, higher in protein, and with a broader range of micronutrients. For people, that is a good thing. For the environment, it’s often not. For farm animals, it’s definitely not.

Again, we’re now in a much better position to provide people with a complete and nutritious diet that does not rely on high levels of meat and dairy consumption. Many people now have access to — and can afford — a wide range of plant-based foods.8 The right combination of cereals, peas, beans, and fruit and vegetables can be nutritionally complete (as long as someone also buys vitamin B12 supplements or eats foods with them already added), but it does require some knowledge of what a good balance of foods looks like.9 It’s easier for someone to get all of their nutrients in without paying much attention to their diet if they include some meat and dairy. But it’s definitely not impossible to do so without them. It just takes more effort.

We’re also getting much better at creating meat-like products without the animal. This is the most viable way for people to eat less meat, as it offers people a direct substitute. It’s replacing a plant-based burger for a beef one; a plant-based mince in a bolognese; meat-free “chicken” pieces for chicken strips in a fajita bowl. Some might find that prospect depressing, but to me, it looks like the most realistic path to a world that eats less animals.10

There are other examples of where the trade-off between human prosperity and environmental impact can be broken. In some cases, it has been. There is the opportunity to move away from a zero-sum world. Here, I always emphasise that it is an opportunity, not an inevitability. There’s no law that says this will happen. It’ll only happen if we (I say as a collective “we”) make the right choices: invest in the right solutions, direct policies and structure incentives in the direction we want to go, and allocate resources to where they are needed the most.

Fail to do this, and we risk sliding backwards, with human living standards stagnating in much of the world, and environmental pressures starting to bite us back.

But by doing so, we can envision a world in 2050 that is better than it is today. For the then nine billion people alive, and the generations that come after us.

The world is still awful, but the data shows that it can be much better

One final thing.

These positive developments — whether in human development or environmental progress — do not mean the world today is good, or that we should be happy with where we are. 10% of the world still lives in extreme poverty. 300,000 women die in childbirth every year. People still die from diseases we can prevent. Hundreds of millions go hungry.

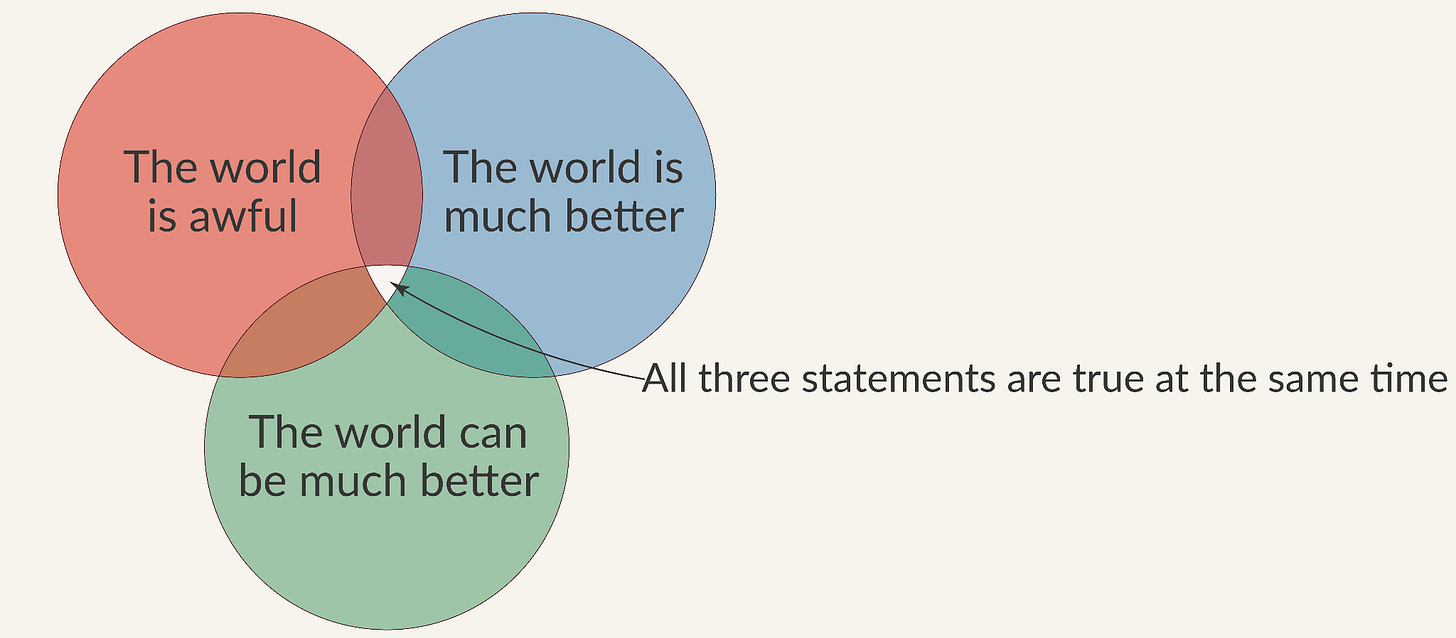

One of our key frameworks at Our World in Data — where we focus on the global data on these huge problems — and coined by Max Roser, is that three statements are almost always true at the same time:

The world is awful

The world is much better

The world can be much better

Take the metric we looked at earlier: child mortality. Five million children still die every year, mostly of causes that are preventable. This is awful, and I wish that we put more resources behind tackling this.11 But we are also doing better than our ancestors: rates have fallen from 50% to 4%. In the past few decades, the number of children dying each year has halved. Finally, we know the world can be much better. As I said, many children are dying from causes and diseases that are preventable. Many countries have rates well below the global average, showing us that more can be done.

Holding these three statements in our heads is hard. It also makes public discussions difficult. If someone says we’ve made progress on child mortality [or climate change, or air pollution, or any other issue], the instinctual pushback is that the person is saying that these problems are solved, or don’t matter. But both statements can be true at the same time. In fact, that’s nearly always the case.

This isn’t really different from the Brundtland definition of sustainable development:

“development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”

This data comes from the paper by Anthony Volk and Jeremy Atkinson.

Volk, A. A., & Atkinson, J. A. (2013). Infant and child death in the human environment of evolutionary adaptation. Evolution and Human Behavior, 34(3), 182-192.

F.E. Johnston, C.E. Snow (1961) – The reassessment of the age and sex of the Indian Knoll skeletal population: Demographic and methodological aspects. In American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 19, pp. 237-244.

Ran Barkai, Jordi Rosell, Ruth Blasco, and Avi Gopher (2017) – Fire for a Reason: Barbecue at Middle Pleistocene Qesem Cave, Israel. In Current Anthropology; Volume 58, Number S16, August 2017, Fire and the Genus Homo.

Owen Jarus – Egyptian Mummies Hold Clues of Ancient Air Pollution. In LiveScience.

Whenever I mention “technologies”, people assume that I’m saying technological change alone has achieved this. Of course, the political backing of these solutions, investment, and socioeconomic systems that enabled them are all crucial inputs into how they came to be.

Here, people will argue that renewable energy technologies are not free from environmental impacts at all. I agree. No energy source has zero impacts. But they do have much lower impacts, and can be integrated into a much more sustainable system of recycling and reuse, rather than continuous extraction. I’ve covered quite a lot of questions on the mining and waste impacts of technologies like solar and wind on this Substack (and in my new book Clearing the Air). The point is that they are not mining or waste-free, but even on those measures, they are less impactful than fossil fuels. And, there are things we can do to improve them.

Note that I don’t think or expect that the world’s poorest countries are going to alleviate poverty and go through a development pathway that uses zero fossil fuels. It is unfair to expect or demand that. But I do think that with the rise of cheaper low-carbon technologies, they can go through a much cleaner development pathway than today’s rich countries did.

Granted, it’s still the case that billions of people cannot afford a “healthy diet” that meets nutritional guidelines, with or without animal products.

There are possibly exceptions to this: young children, pregnant women, and people with particular health conditions are more susceptible to deficiencies.

To be clear: while I am a vegan, I’m not saying we should switch to zero meat and dairy tomorrow. That’s also not realistic, and such a dramatic shift would have negative impacts on human nutrition. My point is that improvements in agricultural productivity and shifts towards more plant-based diets, if done thoughtfully, could dramatically reduce our environmental impact without sacrificing nutrition.

If you want to help the world make progress, one way you can contribute is by donating to highly effective charities. Givewell.org is a charity evaluator that works hard to analyse the performance of programs and make recommendations on where to donate. I’ve signed the “Giving What We Can” pledge, where I donate 10% of my income to effective charities. I give most of it to those working on underrated problems in global health. When I make ad-hoc donations, I usually give to the Against Malaria Foundation (and people often do this as a birthday gift).

Thank you! The best and most balanced summary on this complex discussion I've seen! Keep going Hannah.

This was a fantastic read, Hannah. Your work is always amazing. Please keep sharing these insights and information. You have a wonderful way of making issues relatable and understandable. It's inspiring. Thank you!