Eating wild animals might be sustainable for the few, but not for the many

Some back-of-the-envelope calculations on how many it could feed.

I’ve written a lot about the environmental impacts of our food systems. People often underestimate the impact of what we eat on everything from climate change to land use, biodiversity loss, water use, and pollution. For most people: if you want to reduce the environmental impact of your diet then eating less meat and dairy is the best place to start. That’s where you’ll have the largest impact.

Our livestock systems today are big. Not just in terms of land use, but the number of animals we slaughter every year. It’s over 80 billion animals (or hundreds of millions a day) and that’s just for those on land. Include fish and shrimp, and the total is in the trillions. Most of those animals are factory-farmed, living pretty miserable — and often painful — lives.

Some of those who are concerned about the environmental and welfare impacts of their diet either reduce how much meat and dairy they’re eating, or cut it out completely. I did the former then progressed to the latter.

But another alternative that I get asked about a lot, and goes through popularity waves in the media, is consuming wild meat instead.

“I’ve heard that wild meat is much more sustainable, is it better for me to eat that?”

Usually when I speak to people about this, they start getting bogged down in metrics about carbon footprints. But I think that these standard environmental footprint metrics are often missing the point when it comes to the sustainability of wild meat. Or, at least, it’s not the climate impact that’s the biggest “problem”: it’s the fact that we eat a lot of meat, and there’s not that much wild meat out there. The biggest limitation is not molecules of carbon dioxide, but the risk that we quickly run out.

To test this, I wanted to run some quick numbers on how supply of wild meat might stack up against demand. How long could wild meat keep us going for?

Note that some readers will think that we shouldn’t eat wild animals either, for ethical reasons.1 That’s fine and valid. But this article is not about the morality of eating meat, which is a whole separate discussion. It’s purely trying to get a sense of how current levels of meat consumption compare to how much meat is available from wild sources.

How many deer could the UK eat?

Let’s take the UK as an example. Overpopulation of deer, which can negatively impact landscapes and other wildlife, is seen as a problem. Wild venison, then, is sometimes promoted as a sustainable food choice.

Now, this can make sense for some people. But is it good general i.e. population-wide advice?

Some back-of-the-envelope calculations.

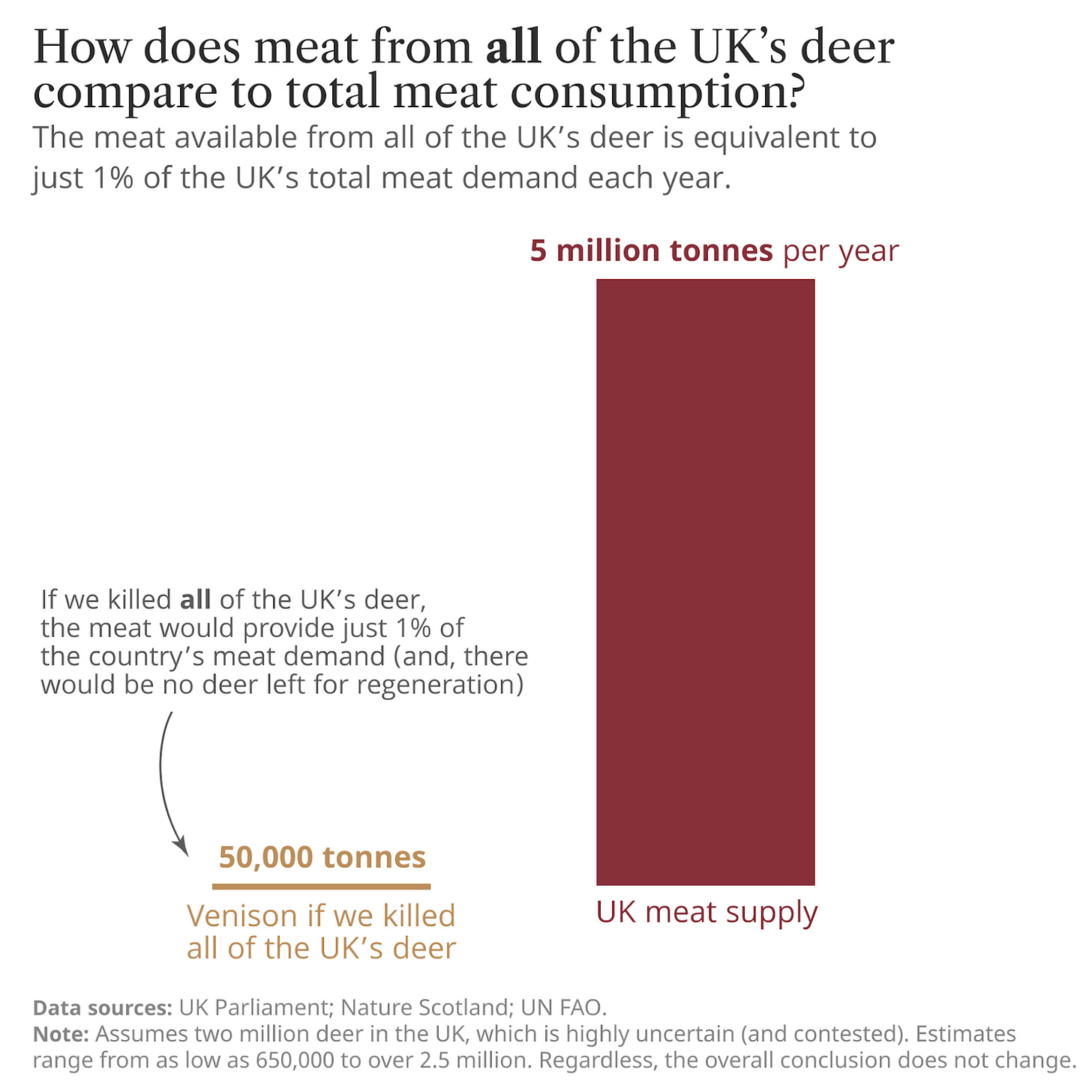

Here, I’m going to assume there are around 2 million deer in the UK. Now, this is a particularly contentious figure (I didn’t know how controversial it was in some groups until I started trying to find a reasonable estimate). It appears to be a headline number that is quoted a lot, and too confidently given the uncertainty. The reality is that no one really knows this figure with high accuracy.2 Estimates range from as low as 650,000 to 2.5 million. I’ve seen others claim that it’s even higher.

I am using this 2 million number, knowing it is not perfect and will make some people angry, but as we’ll see, the choice of figure won’t change the overall conclusion. If the truth is closer to 650,000, then my point is even more obvious. If there are actually, say, 4 million deer, we can just double the final result.

You might get 25 to 30 kilograms of meat from one deer.3 That’s around 50 million kilograms (or 50,000 tonnes) of deer meat for the entire UK.

Sounds like a lot.

But how much meat do Brits eat? Around 75 kilograms per person per year, which comes to around 5 billion kilograms for the country as a whole.

If we killed every deer in the UK, it could maybe supply 1% of our meat consumption — or three days’ worth of meat. Of course, there would be no deer left, so after three days, our entire “wild meat” transition would be over.

Realistically, we would never kill all our deer at once. I’ve heard people recommend a “sustainable” cull rate of around 20% of the population (again, this is a very contentious figure and depends on population dynamics). So we need to divide our 1% of meat supply by five, giving just 0.2%. That’s around half a day of the country’s meat.

The only way this works as general dietary advice is if:

Everyone eats a lot less meat than they currently do. Even then, it’s still going to be a pretty small share of total meat supply.

It’s very clear that people can only eat wild venison very rarely. And by that, I mean one meal a year or something.

Most of the population are resistant to eating venison, or it’s too expensive, so they would never take this advice anyway (this doesn’t seem that implausible to me).

Again, this can work as advice for some people. I’m not saying that your cut of venison is unsustainable. On many metrics, it’s better than farmed livestock. Clearly, 20% of the UK’s deer would provide quite a bit of meat for some consumers. But it does not scale to the population as a whole, and I therefore think it’s not great general advice to dish out.

As I said above, the exact number of deer in the UK is highly uncertain. If there were only 650,000 deer, the percentages would be even smaller. If there were as many as 4 million (which I’m using as a very high estimate), it’s still just 0.4% of the country’s meat.

How much can the world rely on wild meat?

Maybe Brits just eat a lot of meat, and live on a small island without many animals. How do the numbers stack up globally?

Not much better.

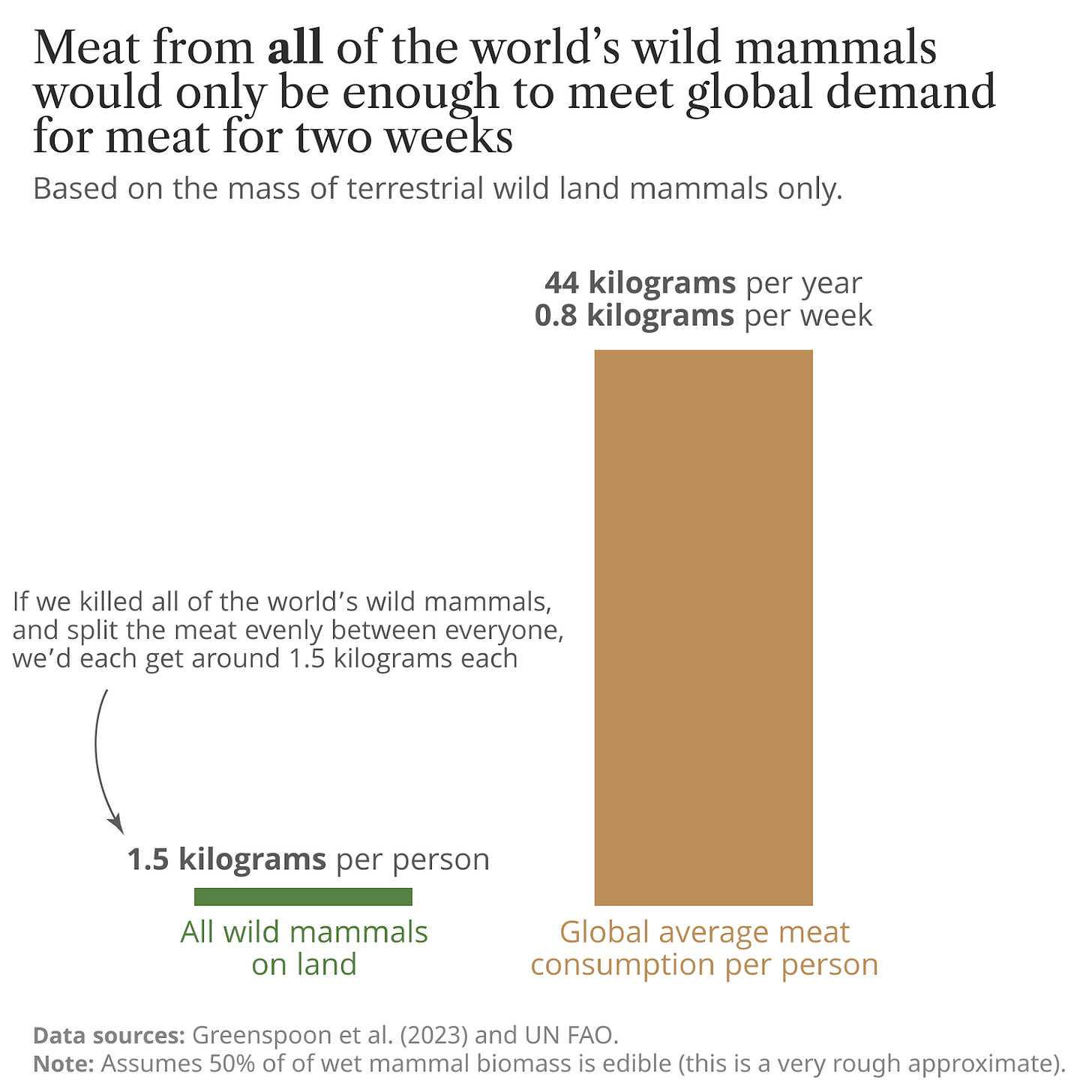

Let’s be “generous” and say that we don’t just restrict it to deer. All of the world’s wild mammals are available, from elephants and rhinos to mice. How we’re going to catch them all is beyond me, but let’s not ruin the hypothetical.4

Wild mammals on land weigh around 20 million tonnes, equivalent to 3 kilograms per person on Earth.5 Not all of that mass is going to be edible, so let’s take a very rough estimate of a 50% “cut”. That would be 1.5 kilograms per person.

Globally, meat supply is around 44 kilograms per person per year (this doesn’t include fish).6

This means that all of the world’s wild mammals in the world would meet just two weeks of our demand for meat. Within a fortnight, they’d all be gone, and their populations would not rebuild.

If we were to also include mammals in the ocean (mostly whales), we’d still only have enough for just over one month.7

Let me be clear: some populations do rely heavily on wild meat (but in smaller quantities than people eat in many high and middle-income countries today). Many of our ancestors ate wild game, too. For some, it’s an essential source of nutrition and is not necessarily unsustainable.

My point is not that this is “wrong”. It’s that this simply doesn’t scale for 8 billion people. Especially not with our current levels of meat consumption (which, globally, are still increasing). It might work for thousands, or even millions, but not for billions. If we were to all eat in this way, animal populations would quickly disappear (and we’d be left without any wild animals or any meat).

I have lots of nutritious alternatives, and I’m happy with my meat-free diet, so I wouldn’t eat wild animals either.

Scotland's Nature Agency says the following:

"There is no definitive figure for the size of the overall population of deer. The most recent estimates suggest that there are up to 400,000 red deer on open ground and up to 105,000 in woodlands, as well as up to 300,000 roe deer, 25,000 sika and at least 8,000 fallow deer.

However, because deer are highly mobile, living on extensive open hill ground and/or in woodland, getting a more exact estimate of populations and their trends across Scotland is complex and costly. Across the uplands, deer are typically counted from the air using helicopters and from the ground by people on foot. NatureScot is currently exploring alternative methods of counting such as using drone and fixed wing aircraft equipped with sophisticated camera technology. Estimating woodland deer numbers can be more challenging but dung counting, thermal imagery and drones can be used.

NatureScot is currently also carrying out further work to model deer populations to provide more accurate estimates of numbers and densities."

I didn't anticipate spending time on hunting forums for research, but here we are...

Of course, this also hinges on the assumption that people would happily eat a whole host of mammals they probably wouldn’t.

Greenspoon, L., Krieger, E., Sender, R., Rosenberg, Y., Bar-On, Y. M., Moran, U., ... & Milo, R. (2023). The global biomass of wild mammals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(10), e2204892120.

This is based on data from the UN FAO, which reports food available for consumption in shops, restaurants etc. We don’t know exactly how much people put into their mouths. So this figure is the total amount we eat, plus wastage.

The biomass of marine mammals is estimated at around 50% more than land mammals. Hence the two combined is probably around 5 weeks’ worth of meat supply.

Bar-On, Y. M., Phillips, R., & Milo, R. (2018). The biomass distribution on Earth. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(25), 6506-6511.

“Morality”? Instead of mortality?

Is the next logical step to write an article on cannibalism? ;-)