The world is not going to pass its 1.5°C warming target in the next few years, but it's a signal of what's to come

What a temporary rise above 1.5°C means for our climate targets.

In the last week, you might have read one of the following headlines:

Global warming set to break key 1.5C limit for first time – BBC

World likely to breach 1.5C climate threshold by 2027, scientists warn – The Guardian

Global warming likely to exceed 1.5C within five years, says weather agency – Financial Times

Global temperatures likely to rise beyond 1.5C limit within next five years – The Independent

Many will read these headlines and think we’re about to pass our 1.5°C target in the Paris Agreement. But that isn’t true.

None of these headlines really capture what this finding means. And if they do explain it, it’s buried more than halfway through the article.

In this post, I wanted to clarify what these numbers mean, because they can easily get confused or misrepresented.

Now, I’ll say it before you do. I’m not here to ‘downplay’ the severity of climate change. I’m not here to say that because we haven’t passed 1.5°C, climate change is not serious. Or that we won’t eventually pass 1.5°C (because we will). I’m not trying to dampen the urgency to act.

I’m trying to help people understand what these numbers mean. That’s important for several reasons that I’ll come to later.

Where did this estimate come from?

These numbers come from the latest report from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). The WMO is a great and trusted organisation, and publishes an update of warming projections every year.

The report states the following:

“The chance of global near-surface temperature exceeding 1.5°C above preindustrial levels for at least one year between 2023 and 2027 is more likely than not (66%).”

What this means is that between now and 2027, it’s more likely than not that for one or two years the average temperature will go past 1.5°C. Now, this is not guaranteed: there’s around a two-thirds chance it does, but also a one-third chance that it doesn’t. So “more likely than not” is a reasonable summary.

In the same report, the WMO notes that scientists think it’s unlikely that the five-year mean temperature will rise above 1.5°C.1

In other words, the WMO thinks it’s likely that by 2027 there will be a temporary rise above 1.5°C for a year or two, but that this will not be a permanent change.

Why would temperatures go above 1.5°C temporarily?

There are two reasons why we’d expect temperatures to temporarily go above 1.5°C in the next five years. The first obvious one is that the world is still warming: total CO2 emissions are as high as ever, and that means more warming.

But that alone wouldn’t cause us to go above 1.5°C in the next few years. We’re also heading into what’s called an ‘El Niño’ phase. You might have heard of something called ‘ENSO’. It’s short for ‘El Niño Southern-Oscillation’ This is a meteorological cycle that happens on a timescale ranging from a few to 7 years, and has a warm (El Niño) and cold (La Niña) phase, with a ‘neutral’ phase in-between [I’ve provided more technical details in the footnote if you’re interested].2

We shouldn’t confuse these ENSO phases for the global warming that we’re seeing today. Climate change is being driven by a persistent push of global temperatures upwards. El Niño and La Niña phases are just smaller fluctuations that sit on top of it. Even though La Niña phases are supposed to be ‘cool’: the temperatures in these ‘cold’ years are still much higher than the ‘warm’ El Niño phases from decades ago.

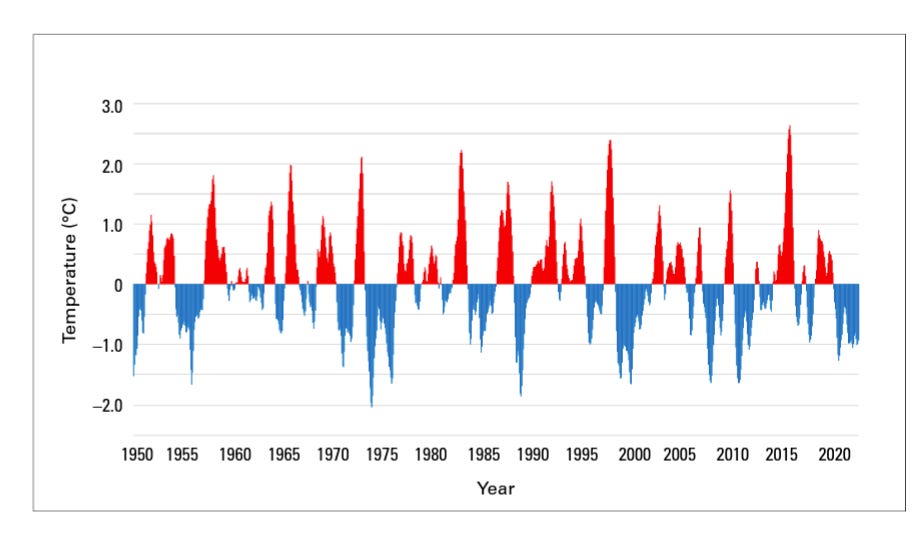

In the chart below you can see the timing of these different phases from the NOAA’s Oceanic Niño Index. These are temperature anomalies in the central tropical Pacific Ocean – they are not changes in the global average temperature. That’s why they’re higher than we might expect.

As seen in blue, the world has been in a cool La Niña phase. We expect that in the next few years we will ‘flip’ into a red El Niño one. That will cause a temporary ‘spike’ in global temperatures, and scientists think that this ‘spike’ could go above 1.5°C. As they put it, it’s “more likely than not”. Temperatures will drop a bit again once we move out of the El Niño phase, so it’s unlikely that we’ll stay above 1.5°C for long.

A temporary rise above 1.5°C does not mean we have passed the Paris Agreement target

So, what’s wrong or misleading about the headlines above?

The first is that some refer to our climate targets as thresholds. This is a bad framing of the climate problem. When you refer to 1.5°C as a threshold, you tell people that something dramatic and substantial changes. People imagine it’s a tipping point into oblivion. In reality, there is nothing particularly special about ‘1.5’. It’s not that as soon as we move from 1.49°C to 1.5°C, we immediately set off a bunch of tipping points. Climate risks increase with warming (and increase more once we get into the world of 1.5°C, 2°C or more). But 1.5°C is not a threshold or a tipping point.

This framing is even worse when you tell people that we’re going to break this ‘threshold’ in the next few years. You tell them that the world is a few years from catastrophe, which is not true.

The second problem with these headlines is that they either state or insinuate that in a few years we’ll pass the 1.5°C target (or ‘limit’ as they put it) in the Paris Agreement. Again, this is false.

In fact, the WMO says this clearly in their press release. And some articles note it at least halfway through, for the rare few that make it that far.

“This report does not mean that we will permanently exceed the 1.5C level specified in the Paris Agreement which refers to long-term warming over many years," said WMO Secretary-General Prof. Petteri Taalas.

The Paris Agreement was not about limiting the temperature increase in any given year to 1.5°C. That’s ‘weather’, not climate. And this confusion (or deliberate miscommunication) of weather and climate is what we criticise deniers for (they use one cold snap to claim that global warming is a hoax).

To say that the Paris Agreement target had been passed, the climate – which is averaged over several decades – would be to be above 1.5°C. To say for sure, this would mean the average over 20 years.3

Some would argue that 20 years is too long. Instead, we might use the five-year smoothed average trend (similar to the smooth line you see on charts like the one below). Once that’s above 1.5°C, we might say that we’ve crossed that level of warming (even if it wouldn’t yet be passed our Paris target).

It’s unlikely that the world will pass an average warming level of 1.5°C until the 2030s. Certainly not in the next five years.

This distinction between long-term warming and single-year temperature changes is important. Many climate impacts tend to happen through the build-up of energy and temperature over time. Most are not caused by a sudden, single-year spike in temperatures. The negative climate impacts that scientists project are therefore based on long-term temperatures being above 1.5°C.

In fact, the world has already gone above 1.5°C for brief period of time. Certainly on the timescale of days, but there have also been months that have broken this line. Below you can see the temperature anomalies for the month of March in every year since 1850. This data and chart is from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA).

Notice that in March 2016, the temperature anomaly was up at 1.35°C. Now, that’s the temperature change relative to the average between 1901 and 2000. But as you can see for the early data in the chart, pre-industrial temperatures were 0.2 to 0.3°C lower than this baseline. That would mean the total temperature anomaly in March 2016 was probably more than 1.5°C – close to 1.55 or 1.6°C.

If the Paris Agreement target was based on us passing 1.5°C temporarily, we’d have failed just three or four months after signing the agreement. But that’s not what the Paris Agreement is based on.

Why is this a problem? Doesn’t it just spark urgency?

My contention above might seem pedantic to some. Okay, maybe the headlines are not technically correct but they tell us that the world is warming quickly, and that is an important message. Does a small misunderstanding like this matter? Maybe it gives people the urgency they need to get moving?

We should never miscommunicate or exaggerate on these issues to drive action. There is really no need: the truth is bad enough. And these misconceptions could actually lead to less action, not more.

First, there is the impact on peoples’ mental health. Many people (wrongly) believe that 1.5°C is a catastrophic boundary: that once we cross it, the fight is over. To tell people that this is coming in a few years is to tell them that the end is near.

Second, it’s important for the integrity and trust of scientists. Scientists did not previously project that we’d pass the 1.5°C target in the next few years (because we won’t). But when it’s framed as if we will, it seems like this has been a complete blind spot for them. Either something has changed in the last year that scientists did not foresee, or their previous estimates were way off. In either case, it makes them seem incompetent.

Third, it gives ammunition to climate deniers. There are a range of negative impacts that are projected to happen in the 1.5 - 2°C range. Many won’t happen after just one or two years at 1.5°C. But skeptics will use this to their advantage. “See, they said that X was going to happen at 1.5°C. We’ve reached that point, and it hasn’t happened. Scientists have been lying.”

Fourth, to stop us spiralling into a state of panic. Now, some of you will argue that we should be in a state of panic. But there’s a difference between that and being in a state of urgency. Urgency pushes us to work quickly and effectively. Panic leads us to poor and divisive decisions. Urgency tells us we need to really step up our efforts and decarbonise much more quickly; panic tells us we need to dismantle our systems and decarbonise in the space of a few years. The former is what we need; the latter would be a disaster.

Finally, it can stall rather than accelerate climate action. Telling people that we’re only a few years from our Paris Agreement target is like telling them that our time is up. There’s nothing to be done. Any action is hopeless. This couldn’t be further from the truth: while temperatures continue to rise, decarbonisation is happening and we are making progress (just not fast enough).

A final summary

To conclude, what seems likely to happen in the next five years?

The current warmest year on record is 2016 (this was during a very strong El Niño event). It’s very likely that we will break that.

Global temperatures averaged over the next five years will be higher than the average for the previous five.

It’s more likely than not (but not a certainty) that global temperatures will go above 1.5°C for at least one year. This is likely to be a temporary rise above 1.5°C, a ‘spike’ caused by El Niño.

It’s unlikely that the five-year average temperature will be above 1.5°C. Temperatures will rise during El Niño then fall back a little.

A temporary rise above 1.5°C does not mean we have passed the 1.5°C temperature target in the Paris Agreement. That target is based on long-term warming. To pass this target, the global temperature averaged over 20 years would need to be above 1.5°C.

Most importantly, we need to peak and reduce carbon emissions quickly – this is true regardless of whether we’re at 1.3°C, 1.5°C, or 2°C of warming.

It states that “It is unlikely (32%) that the five-year mean will exceed this threshold.” That means the probability of the five-year average going above 1.5°C is the opposite of what it expects for one year (a one-third likelihood that this does happen; a two-thirds chance it doesn’t).

The El Niño Southern-Oscillation (ENSO) is a meteorological cycle across the tropics and sub-tropics, mostly notably in the tropical Pacific. The move between the warm (El Niño) and cool (La Niña) phase is determined by changes in the wind pattern and sea surface temperature.

During ‘normal’ or ‘neutral’ conditions, there are easterly trade winds that move warm water away from the Western South American coast westward, towards Australia. Warm water at the surface moves away from Chile and Peru towards Australia, and this causes colder, nutrient-rich water to come up to the surface along the South American coast. This is usually a great time for fishing stocks.

During an El Niño phase, this westward movement of warm water either weakens, or reverses, which means there is less of a temperature gradient required for cold water to upwell from the depths of the ocean. That means the tropics and subtropics are warmer than normal, causing average global temperatures to be higher.

In the La Niña phase, this westward movement is stronger than normal, meaning the upwelling of cold water is even greater. That’s why it’s known as the “cool phase”.

In fact, the goal is to “limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C” by the end of this century. What this means, exactly, is up for debate. Some modelled mitigation scenarios exceed 1.5°C then draw temperatures back down below 1.5°C by 2100. These are called “overshoot” scenarios. Whether these scenarios are compatible with the Paris Agreement is contested. For more context on this, see this post by Dr Carl-Friedrich Schleussner and Gaurav Ganti in Carbon Brief.

Or, for the more technical version, see their paper:

Schleussner, C-F, et al. (2022) An emission pathway classification reflecting the Paris Agreement climate objectives, Communications Earth & Environment.

Hi Hanna, as always a great piece. However, the text in the Paris agreement is often misquoted and I feel like this could be a nice addition to the article as well.

The official agreement is

"Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C".

So even when the 1.5 mark is passed, the agreement still holds, in my interpretation at least.

Great article, thank you!

It is so good to have a voice of reason in an ever growing crowd of self-interested alarmists, and college-dropouts masquerading as "experts".