Deforestation in the Amazon peaked decades ago. Can we get it to zero?

The new Brazilian president, Lula da Silva, has committed to ending deforestation by 2030. How achievable is this?

The Amazon is the largest rainforest in the world, and home to some of its most diverse ecosystems. We need to protect it, which means ending deforestation as soon as we can.

Today – on the 1st of January 2023 – the new Brazilian president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (known as ‘Lula’) takes office. He has committed to ending deforestation by 2030 and protecting indigenous rights.

This would be one of the world’s most important environmental successes to date.

How realistic is this goal? How far away is Brazil from it?

Deforestation in the Amazon is already well past the peak

Let’s start by getting some grounding on where we are today.

With a constant stream of headlines about the burning Amazon burning, it’s hard to get a sense of how bad things are. You might imagine that we are at the height of deforestation.

Thankfully we are well past the peak.

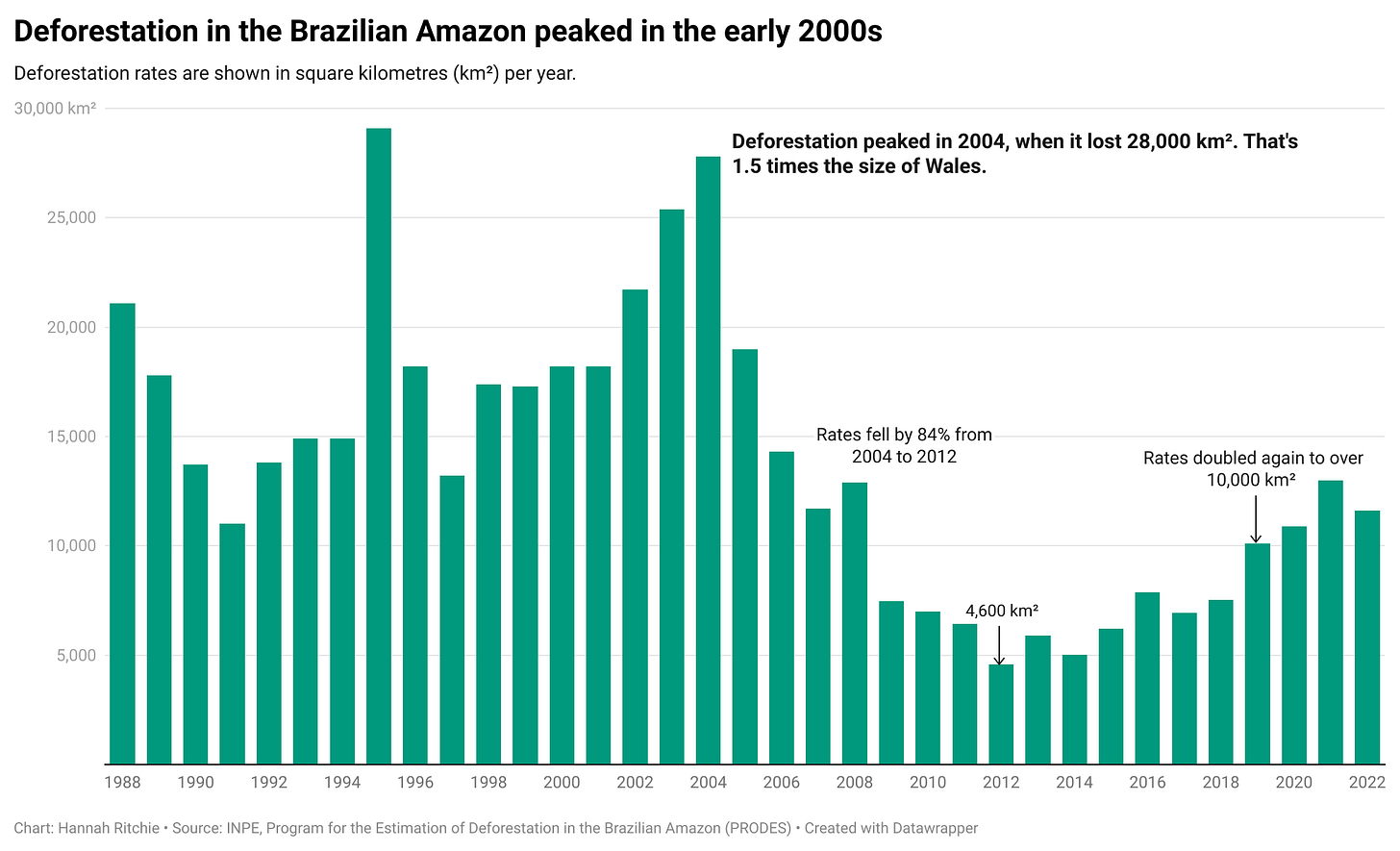

Deforestation rates peaked in the early 2000s when Brazil was losing around 28,000 km² per year. This is almost 1.5 times the size of Wales (every area measurement needs to be compared to the size of Wales).

In the chart, you can see how deforestation rates have changed since 1988.

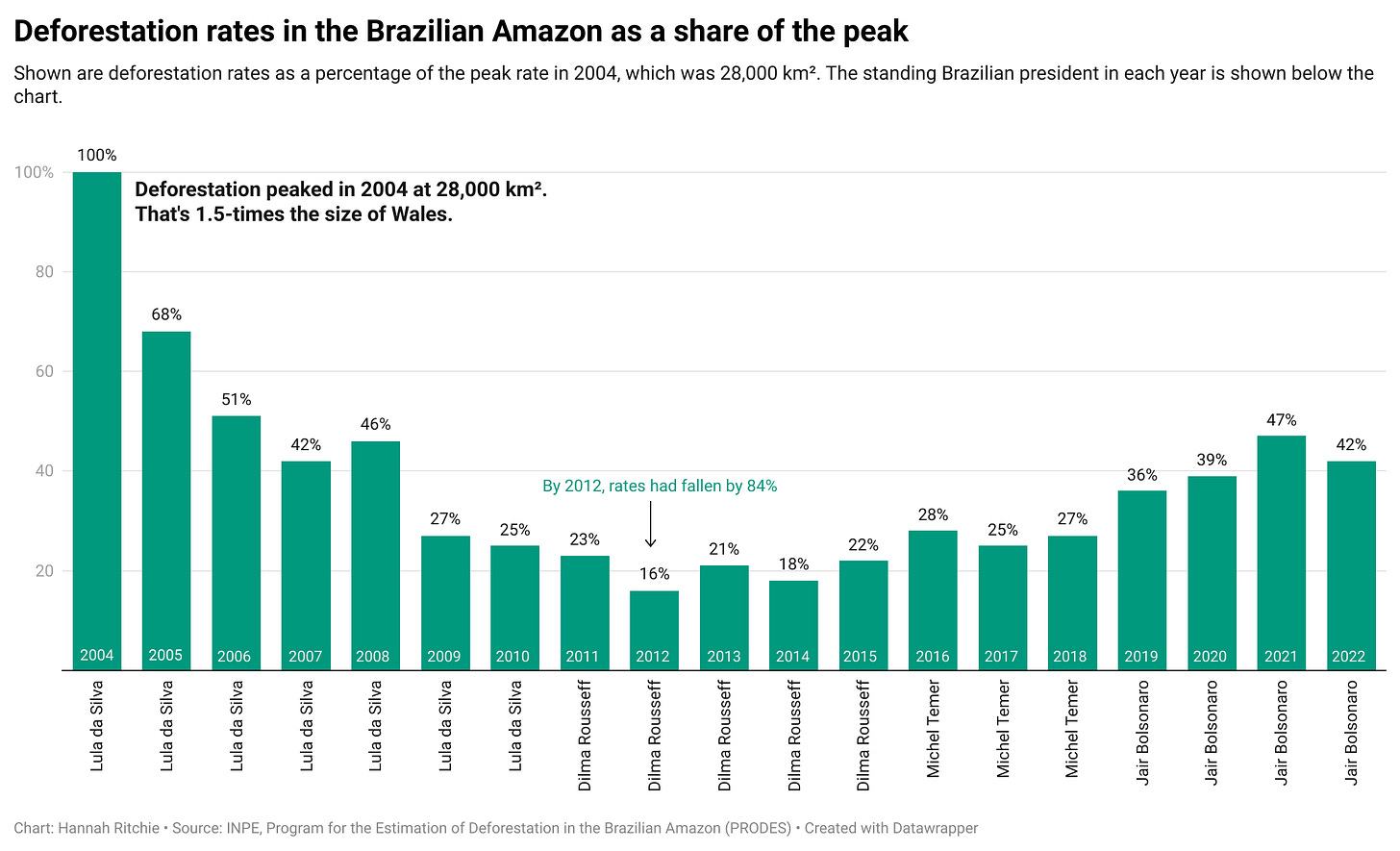

They plummeted in the first decade of the 2000s after Lula took office, falling by 84% between 2004 and 2012. At this low point, Brazil was losing around 5,000 km² per year: a quarter the size of Wales.

They stayed low for several years, before doubling again under Jair Bolsonaro’s presidency. This was a terrible step backward, but we should keep this in perspective: recent rates are still two to three times lower than the peak in the early 2000s.

Deforestation fell by 75% under Lula da Silva’s presidency

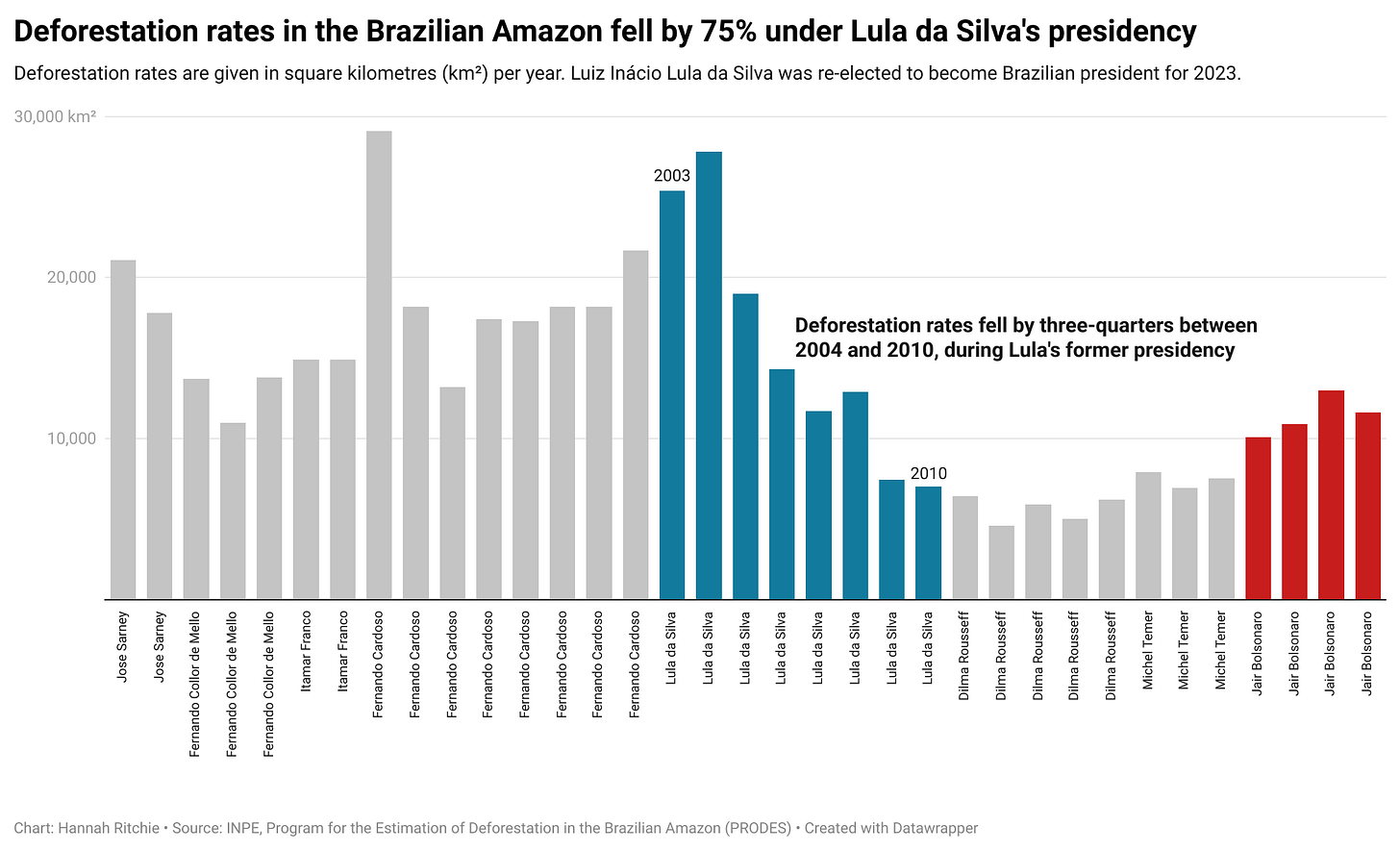

In his former presidency, Lula was very successful in reducing deforestation.

Rates fell by three-quarters between peak deforestation in 2004, and the end of his presidency in 2010.

Deforestation rates stayed low under his successor – Dilma Rouseff, a fellow Workers’ Party politician. By 2012, rates had fallen by 84%.

This is shown in the chart, with Lula’s presidency shown in blue. At the bottom of the chart, you can see the Brazilian president in office each year. The uptick in deforestation under Jair Bolsonaro is shown in red.

Again, this was a damaging reversal of progress but nowhere close to Brazil’s period of peak deforestation.

Could Brazil actually reach zero deforestation?

Lula’s track record on deforestation suggests that if anyone has a good shot of achieving this, it’s him.

It’s going to be a tough task though. Especially as there could be residual impacts of the policies and expectations that Bolsonaro put in place. These will take some time to undo.

But, it’s not totally unfeasible. Analysis conducted for Carbon Brief estimated that Lula could reduce deforestation rates by 90%. How did they estimate this?

Researchers1 modelled what would happen to deforestation under two scenarios:

If Lula took office and implemented the ‘Forest Code’.

If Bolsonaro had stayed in office, with a continuation of current policies.

The ‘Forest Code’ – which dates back to 1965 – is Brazil’s mainstay policy to reduce deforestation. Under the Forest Code, landowners in the Brazilian Amazon have to leave a certain proportion of their land as forest and restore previously deforested land. When it was first proposed, this share was 50% of the land. Since then, it has increased to 80%. But, the legislation has never been put into practice fully.

If Bolsonaro had stayed in office, and the Forest Code was not implemented, deforestation rates would remain high – close to their current levels of around 10,000 km² per year.

In a scenario where Lula implemented it properly, and this was continued through to 2030, researchers estimate that deforestation rates could fall by 90%. Not quite zero, but close.

What else could Lula do to get there?

His first promise is to improve the surveillance and governance of deforestation. Many companies have committed to zero deforestation in their supply chains, but this is hard to enforce without proper monitoring systems.

Next, he can implement a ‘Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) system.2 This was previously approved, but hasn’t been properly put into practice. The PES system provides financial rewards to landowners for the protection of ecosystems, including rainforests.

Finally, he plans to push back against resistance from Brazil’s agricultural lobby. This plays an important role in government and has opposed many of the proposed policies to reduce deforestation. Agriculture – mostly cattle farming, and soy (most of which is fed to animals) – is the leading driver of deforestation.3

Rich countries need to do their part in ending deforestation

Ending global deforestation would be one of our greatest environmental achievements. From slowing biodiversity loss to reducing carbon emissions, the benefits are huge.

Many rich countries have been guilty of pointing the finger and blaming lower-income countries for cutting down their forests. This is hypocritical.

There is a short-term economic cost to halting deforestation. Farmers could make money from growing crops or raising cattle on deforested land. By leaving trees standing, they’re forgoing this income.

Rich countries cut down most of their forests centuries ago, giving them lots of space for agricultural land, and other resources.

If they want others to stop deforestation, they can contribute financially: supporting them with the foregone opportunity costs of using this forested land for something else.

They can also contribute via the private sector by incentivising companies to set zero-deforestation targets, and ensuring that they implement them properly.

Finally, they can monitor the foods that they import, to understand if any of them could be linked to deforestation. The French government is already doing this: it recently worked with the organisation – Trase – to build a dashboard that showed its soy imports, and how much could be linked to deforestation.

There is a real possibility that we could stop deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon this decade. This will be Brazil’s victory, but it’s one that the rest of the world can support.

The Amazon rainforest by numbers

🌳 The Amazon basin covers 7 million km².

🌳 The Amazon rainforest is 5.5 million km².

🌳 60% of the Amazon is in Brazil.

🌳 The rest is spread across various South American countries, including Peru (13%), Colombia (10%), Bolivia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guyana, Suriname, and Venezuela.

🌳 The Amazon accounts for 14% of global forest.

🌳 The Brazilian Amazon is 8% of global forest.

🌳 In 1970, the Brazilian Amazon was 4.1 million km². It’s now 3.3 million km². That means 20% of the Brazilian Amazon has been lost.The analysis was led by Dr Aline Soterroni, alongside colleagues at the University of Oxford, the International Institute for Applied System Analysis, and National Institute for Space Research (INPE).

Ruggiero, P. G., Metzger, J. P., Tambosi, L. R., & Nichols, E. (2019). Payment for ecosystem services programs in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest: Effective but not enough. Land use policy, 82, 283-291.

Pendrill, F., Persson, U. M., Godar, J., Kastner, T., Moran, D., Schmidt, S., & Wood, R. (2019). Agricultural and forestry trade drives large share of tropical deforestation emissions. Global Environmental Change, 56, 1-10.

Geist, H. J., & Lambin, E. F. (2002). Proximate Causes and Underlying Driving Forces of Tropical Deforestation. BioScience, 52(2), 143-150.

Gibbs, H. K., Ruesch, A. S., Achard, F., Clayton, M. K., Holmgren, P., Ramankutty, N., & Foley, J. A. (2010). Tropical forests were the primary sources of new agricultural land in the 1980s and 1990s. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(38), 16732-16737.

Hosonuma, N., Herold, M., De Sy, V., De Fries, R. S., Brockhaus, M., Verchot, L., … & Romijn, E. (2012). An assessment of deforestation and forest degradation drivers in developing countries. Environmental Research Letters, 7(4), 044009.

First I agree with your point.

Why are they deforesting? Where is the needing more land pressure coming from?

I don’t think it’s as simple as throwing money at a problem or governments around the world creating laws. My guess is there are huge monetary incentives to even poor individuals involved. Are we asking them to sacrifice for the greater good?

Very hopeful signs, did not know the deforestation was this steadily decreasing, based on the Bolsonaro headlines I had indeed got the impression that it was as bad as it has ever been. Come to think of it, this was in part based on hearing that deforestation 'doubled', but I hadn't been aware that this was doubled from much lower rates..

What I think is needed from a Lula presidency, as well as subsequent presidents, is a steadfast commitment to implementing policies that in the long term can bring down deforestation, without expecting it to happen overnight. It goes without saying (but it should be said over and over again until it actually happens) that developed nations should be providing funds/expertise to achieve this, as it is something that benefits us all.