China is building more coal plants but might burn less coal

China is adding more coal capacity, but its plants are running less often.

If I got a pound (£) for every time someone said “if solar and wind are so cheap, why is China building so many coal plants?” I’d be able to fund the global energy transition myself.

It is a valid question though. China’s continued build-out of new coal plants doesn’t make much economic sense. Energy analysts see it as the symptom of poor planning; decisions that will lead to underused power plants and stranded assets.

Some analysts think that China’s coal emissions have already peaked – or will peak in the next few years.1 We’ll have to wait and see if they’re right. But the fact that they can even suggest that a peak in coal use is coming, while China is adding more coal plants, seems contradictory.

Both points can be true, though. China could build more plants while burning less coal. It just has to run them less often. Based on data over the last decade or two, that’s exactly what’s happening.

In this post I take a quick look at the data on coal trends in China, and what this might mean for its energy future.

China is still building more coal plants

China is opening new coal plants. It’s one of the few countries in the world that is at scale.

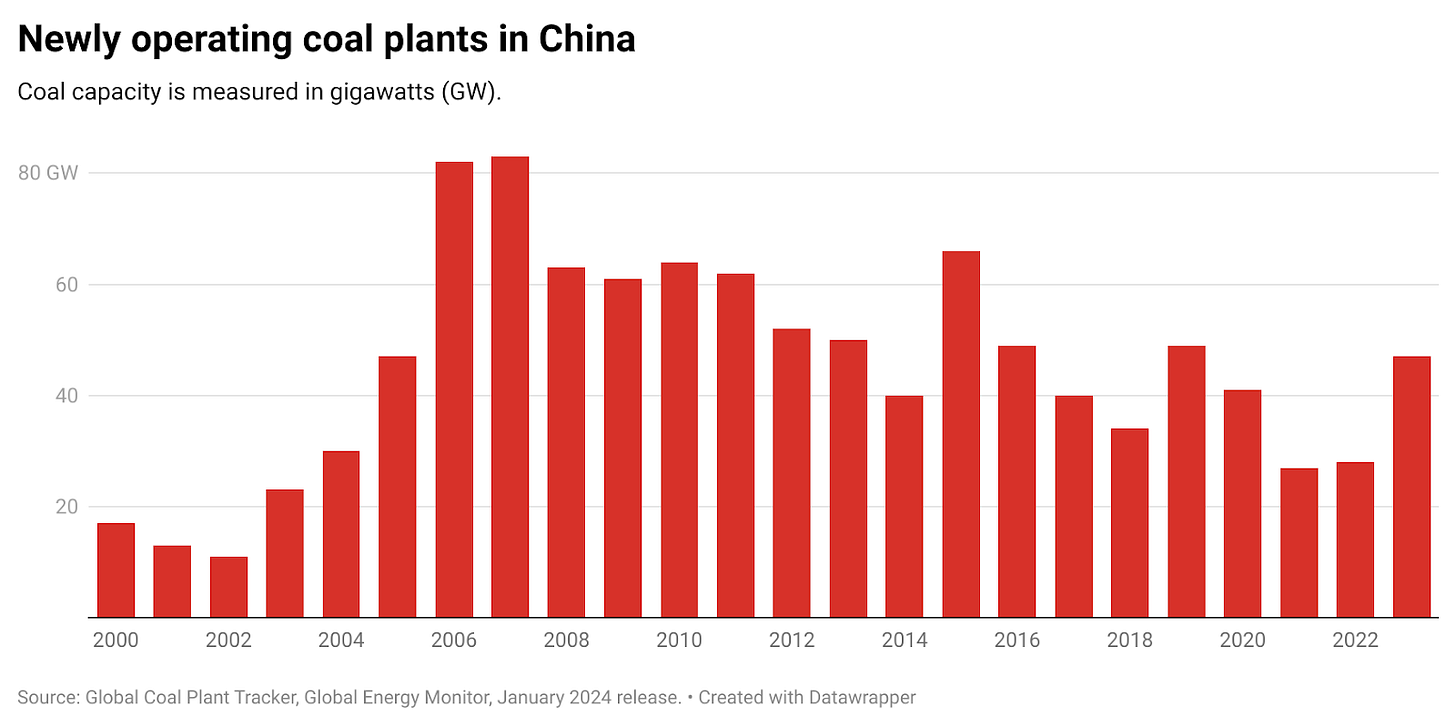

The chart below shows data from the Global Energy Monitor’s Global Coal Plant Tracker. It’s a great resource to track plant openings, retirements, plans, and cancellations across the world.

In 2023 it added almost 50 gigawatts (GW). That’s about the same as the installed capacity in Indonesia, Germany or Japan.

It retired only 4GW, so the net additions were over 40GW.

So yes, China keeps building out its total coal capacity every year.

China’s coal plants are running less often

Power plants usually aren’t running all the time. They’re turned on and off or ramped up and down when they’re needed.

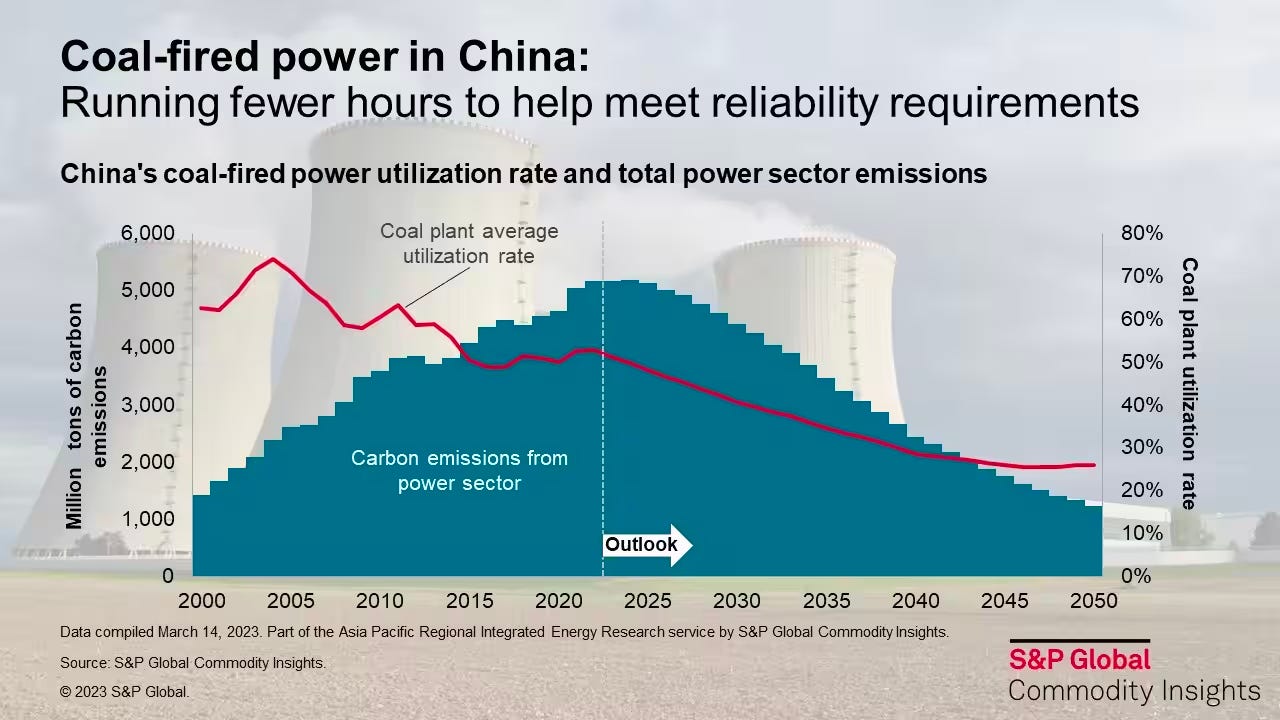

The ‘capacity factor’ of the plant tells us how often it’s running at maximum power. The capacity factor of China’s coal plants has been dropping over the last 15 years. See the chart below from S&P Global Commodity Insights.

In the first decade of the 2000s, plants were running around 70% of the time. They’re now running around 50%. We can also see this in operating hours data from the National Energy Administration (NEA) of China.

If utilisation rates continue to drop, China’s coal use could fall despite it adding more capacity.

Take an analogy. A CEO could hire lots of new people for their company. But if everyone is forced to switch from full-time to part-time contracts, the total hours worked by the company might be lower despite adding a bunch of new recruits.

As the chart shows, analysts do expect coal’s capacity factors to continue to drop. We’ll look at more evidence for this soon.

Many of China’s coal plants are losing money

High coal prices mean that most coal plants in China are operating at a loss. In 2018, almost 50% had a net financial loss.2 Things have only gotten worse: data from the China Electricity Council suggests that more than half of its large coal firms made a loss in the first half of 2022.

The economics of coal plants are only set to get harder. China is building huge quantities of solar and wind, which are essentially free to run once they’re installed. As renewables push down the cost of energy, coal will become less and less profitable.

China is offering ‘capacity payments’ to power plants to keep them online. This provides plants with a source of income even when they’re not being used. Some project that by the end of the decade many coal plants will be making more money from not running than actually producing power. This seems credible if we look at the tumbling capacity factors expected from S&P over the next few decades.

Coal will take on the role of ‘peaker plants’

As low-carbon energy sources continue to grow, they’ll take priority spot in the electricity mix. Coal power will start to take on the role of ‘peaker plants’.

Most of the world is used to gas playing that role. But China has never embraced gas: it doesn’t want another geopolitical burden when it has coal resources at home. So, coal is the ‘flexible’ or ‘peaker’ fuel of choice.

Another nod towards this shifting role of coal is that the Chinese government now has a program mandating “flexibility retrofits” on coal plants so that they can ramp up and down more effectively. If coal was going to maintain its role as the bulk baseload of the energy system, it wouldn’t need to do this.

Why is China overbuilding coal plants?

That still doesn’t answer the question of why China is over-building coal plants.

The first argument is that energy security and steady supplies are its top priority. That might lead them to overbuild ‘just in case’. Last year China’s hydropower output saw a big drop due to devastating droughts. It was mostly coal power that was used to cover the shortfall.

But even if China wants to be conservative, it’s still building far more than it will ever need.

One reason seems to be the devolution of power plant approvals to the provincial level. Plants used to be centrally approved until 2014, when those decisions were passed down to each province. The problem is that each province operates as if it’s in a bubble – it wants to secure consistent and reliable supplies on its own, without relying on its neighbours for any shortfall. That’s an incredibly inefficient way to plan large-scale energy systems, and it means every province becomes overly conservative about its demands.

Provincial leaders are also judged on the economic growth figures within their administration. Approving and building coal plants – regardless of whether they’re needed – can lead to economic activity which looks good on their short-term scorecard but leads to chronic oversupply in the long term.

In an article from the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), analysts present a model of approval rates for coal plants in two scenarios: one where the decision is centralised, and another where it’s decentralised to the local level. They found that approval rates were around three times higher when the decisions were decentralised.

That might not be the only explanation for why China is still building so many plants, but it’s a big one.

Improving grid flexibility and transmissions between provinces will be crucial to stopping or slowing the coal-building spree.

China could burn less coal despite having more plants

We don’t yet know for sure whether China’s coal use is on the brink of a peak. The trends are pointing in that direction. If it continues to build low-carbon energy as quickly as it has over the last few years, it seems likely that solar and wind will cover all of its new demand.

Of course, there could be some curve balls. Perhaps it will try to stimulate a big surge in industrial output and ramp up its coal plants. Seems unlikely, but not impossible.

But it’s still technically and economically possible for China’s coal use to go down while its installed capacity goes up. That’s a paradox that I think most people aren’t aware of. They see China building new plants and assume that its emissions will keep rising.

That’s not a given. What is guaranteed is that China’s evolving energy system will be a gripping watch over the next decade. One that will tip the world’s climate trajectory on to or away from a better path.

Recommended reading/following

Here are a few recommended readings if you want to dig into this topic further.

Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA): China’s Climate Transition: Outlook 2023

Lauri Myllyvirta in Carbon Brief: Analysis: China’s emissions set to fall in 2024 after record growth in clean energy

Lauri Myllyvirta is my go-to source on what’s happening in China’s energy sector.

Global Energy Monitor’s Global Coal Plant Tracker

Here's a list of just a few:

https://www.rystadenergy.com/news/coal-power-peak-solar-wind-emissions

https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-chinas-emissions-set-to-fall-in-2024-after-record-growth-in-clean-energy/

https://ember-climate.org/insights/in-brief/world-close-to-peak-emissions-in-the-power-sector/

Ji, X (2018), “China Reform Institute: Half of thermal power companies face loss, need to increase subsidies imperatively” (original title: 中改院:火电企业亏损近半,需加紧输血造血), Chinareform.org.cn, 4 September.

China is building coal because you can’t replace reliable generating capacity with solar and wind.

The notion that you can has been disproven repeatedly. One day there may be a form of affordable storage which makes this feasible. Meanwhile they have to build dispatchable power. They are building nuclear and coal and gas. Ultimately nuclear will probably replace coal as the stations last much longer.

Would it make sense to build a significant overcapacity of power stations if you were concerned that at some point in the not too distant future you might be involved in a conflict that could result in some power stations being destroyed?