There are many reasons to invest in women's education. Reducing CO₂ emissions isn't one of them.

Reducing fertility rates in low income countries will hardly make a dent in global CO₂ emissions.

“Women’s empowerment is one of the most effective ways to stop climate change”. I’ve heard this claim a lot, and it’s not true.

There are lots of reasons to invest in women’s education, access to contraception, working opportunities, and rights. But climate change is very low on the list.

When people say this, what they’re saying is: there are too many people, and we should reduce the number of children that women have. Specifically, we should reduce the number in low-income countries, because that’s where women have many children.

Women in high and middle-income countries already have less than two children – most are well below the ‘replacement’ level to keep the population stable. Women in low-income countries have 4 to 5 children. In some, the average is 6 or 7.

So when people make this argument, they’re often aiming it at the world’s poorest countries.

What’s true is that with economic development and increased opportunities, women tend to have fewer children. This is a trend that almost every country has followed. Even countries with high fertility rates today have seen some reduction as they got richer.

But will reducing fertility rates in low-income countries have much impact on CO₂ emissions? No. Let me show you why.

The emissions of poor countries are tiny

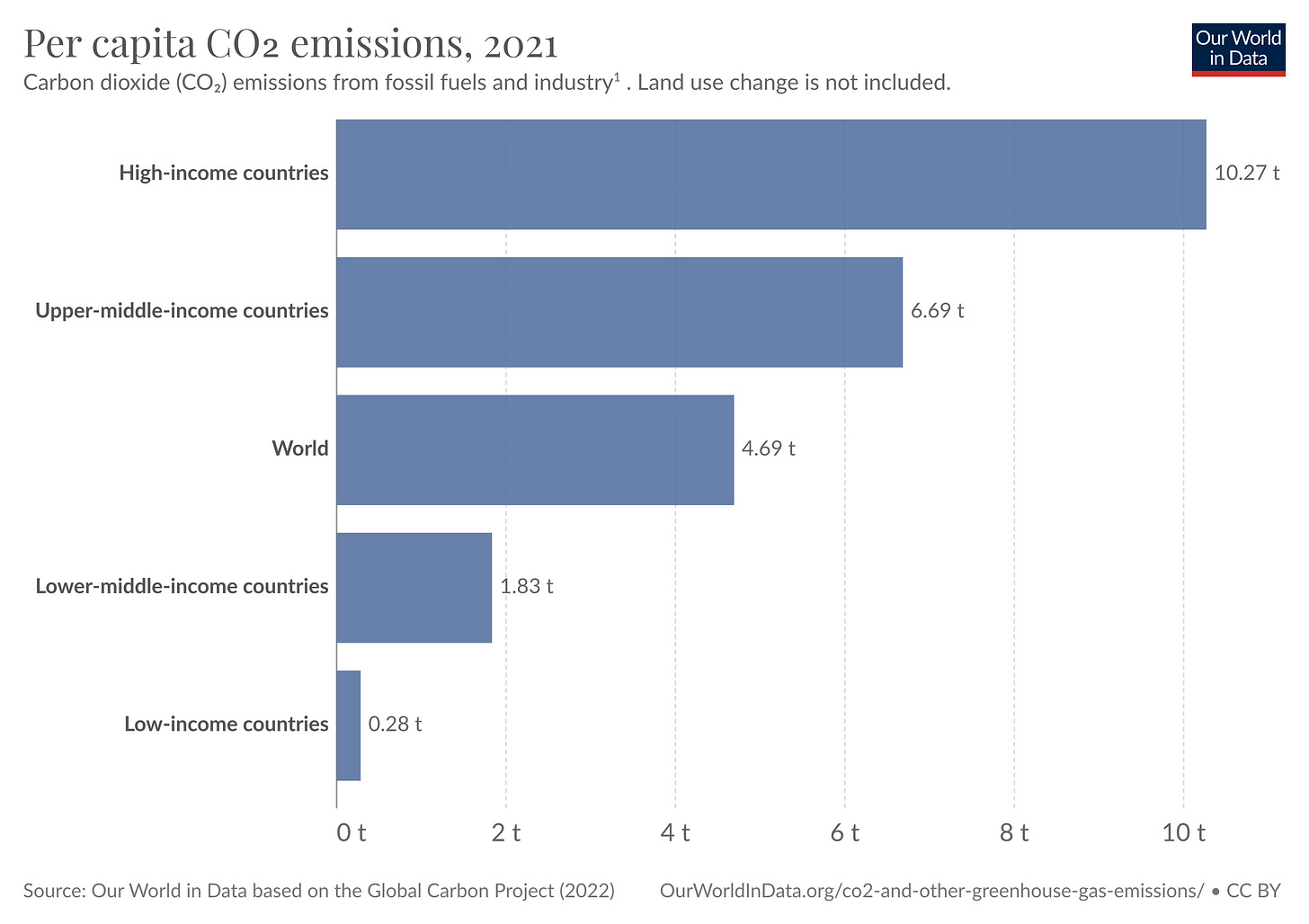

First, let’s look at the world’s CO₂ emissions broken down by income group.1 I’ve shown each group’s share of the global population and CO₂ emissions in 2021 in the chart.

You can see how ‘underrepresented’ the low-income, and lower-middle income groups are. Low-income countries account for 9% of the world population, but just 0.5% of emissions. They’re ‘underrepresented’ by a factor of 18.

Lower-middle income countries are home to 43% of the world, but contribute just 17% of emissions. 2.5-times less.

Another way to look at this is per capita emissions (that’s just total emissions divided by the population). The average person in the world emits 4.7 tonnes of CO₂ per year. In low-income countries, this is just 0.3 tonnes. That’s how much the average American emits every week.2

The point is that the emissions of people with low incomes are tiny. It barely registers on the global thermometer.

Low-income countries could add billions of people, and the impact on global emissions would be minimal

Time for some thought experiments and number-crunching.

Rather than looking at the impact of a decline in fertility, we can look at how high fertility rates – adding lots of people to the world – might affect global emissions.

First, we’re going to assume that fertility rates in low-income countries skyrocket. We’re going to immediately add one billion people, then another, and another.

Important note: here I’m using thought experiments to test the impact on global CO₂ emissions. I’m not looking at problems such as food or freshwater availability. Obviously adding billions of people would have a massive impact on these things in low-income countries.

In 2021, global CO₂ emissions were 37 billion tonnes. Let’s add a billion people to the low-income group. We’d be at 37.3 billion tonnes. That would be like adding an additional France to the world.3 Barely a difference after adding a billion people.

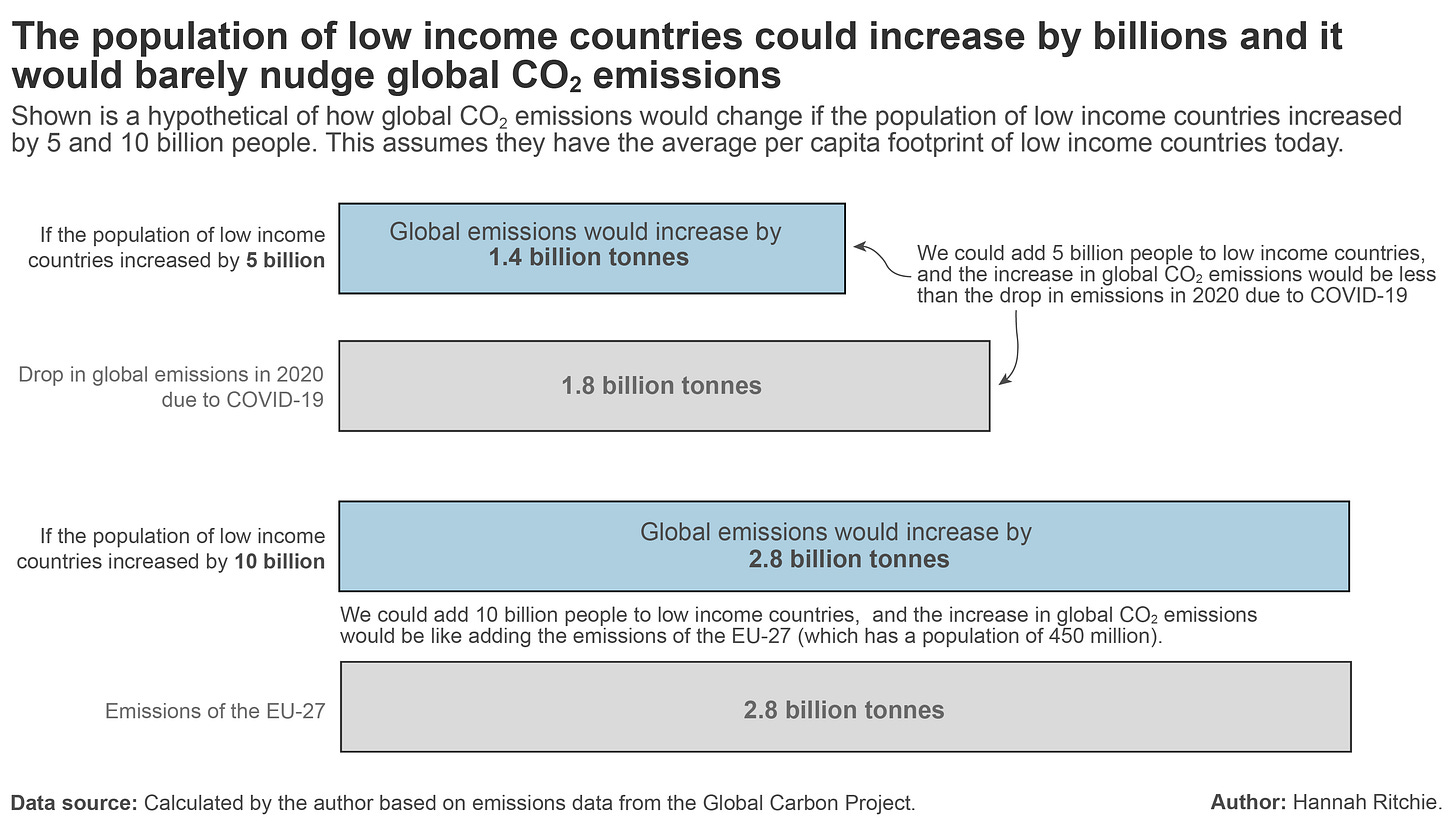

Okay, let’s just keep adding billions. I’ve done this in the chart.

Adding 5 billion people with low incomes would increase emissions from 37 to 38.4 billion tonnes. An increase of 1.4 billion tonnes. That’s less than the drop in emissions in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic (which was 1.8 billion tonnes).

Add ten billion and we’d emit 40 billion tonnes. It would be like adding the emissions of the EU-27.

People in low-income countries emit very little. They could have massive populations, and it would hardly make a dent in global emissions. The notion that fertility rates matter much in this context is wrong.

Adding billions to lower-middle income countries makes a bit of a difference, but not much

So far we’ve focused on the poorest countries in the world. What about lower-middle income countries? Fertility rates there are surprisingly low, but often still above replacement levels.

Let’s see how its population numbers affect global emissions.

We’ll do the same again: add one billion people after another.

An additional billion would take us from 37 to 38.8 billion tonnes of CO₂.

We could add three billion people and emissions would increase to 42 billion tonnes. That increase would be like adding one more US (with a population of 330 million) to the world.

Poor people will hopefully get richer: how would that affect emissions?

We obviously don’t want the world’s poor to stay there. It’s crucial that they make progress in moving out of poverty.

“Population size might not matter much when they’re at low incomes. But it’ll make a big difference if their incomes rise” is a common argument.

Let’s see how this affects global emissions.

We’re going to move countries at low incomes – where fertility rates are high – up an income group. It would be great if they could achieve more growth than this. But on the timescales we’re thinking about – the next few decades – this rate of growth would be a stretch.

Hopefully, further in the future, incomes will increase even more. But on these timescales, the rest of the world will need to have decarbonised economies to tackle climate change anyway. By the time these countries reached high incomes, low-carbon technologies will be abundant, and the footprint of a person will be small.

We’ll do the same as our previous thought experiments, except we’re going to bump up the lives of the poorest in the world. They’re going to have the per capita emissions of lower-middle income countries (and we’ll assume that those emissions are a proxy for the lifestyle at that income).

By simply moving this group to lower-middle income, emissions increase from 37 to 38 billion tonnes. That change alone would make a massive difference to global poverty, and the climate cost is small. If we keep adding billions this rises to 39.3, then 41.3, then 43 billion tonnes.

It makes a bit of a difference, but not when we frame it as lifting tens or hundreds of millions out of extreme poverty and adding billions of people to the world.

Let's invest in opportunities for women, but not because of climate change

Every girl should have the opportunity to go to school. Women should have the right to work and build a career. They deserve access to contraceptives and to have autonomy over their healthcare decisions.

My point is not that these things are not important. They are. It’s just that they are important enough in their own right. Girls should go to school because they deserve the right to go to school. Not so that they will have fewer children that will emit small amounts of CO₂ later in life.

There are so many reasons to invest in these things. But climate change is so low on the list (and that’s coming from an environmentalist). I cannot fathom going into a meeting with the prime minister of a country with high fertility rates and suggesting they should invest in these things because of the impact on global emissions. I hope I’d be laughed out of the room.

If climate-population activists really want to reduce fertility rates they’d be much more effective with arguments that don’t involve the climate at all. There are many things – like poverty reduction and improved population health – that are much higher on the priority list for country leaders.

I've based these calculations on two sources:

Carbon emission figures come from the Global Carbon Project. These estimates include emissions from fossil fuels and industrial processes. Emissions from land use change – which are much more uncertain – are not included.

Population figures come from the UN World Population Division.

Countries are grouped based on the World Bank's Income Groups, which you can explore here.

Emissions and populations are grouped based on the average income of the country. That means it does not adjust for within-country income differences.

In 2021, the average footprint in the US was 14.86 tonnes per person.

Divide this by 0.28 tonnes, which is the average of low-income countries, and we get 53.

That means the average American emits about the same in a week as the average person in a low-income country does in an entire year.

France's emissions in 2021 were around 300 million tonnes (0.3 billion tonnes).

Great analysis, as always. I am convinced.

Hi Hannah, thanks for a great article. Do you know why Project Drawdown still has Family Planning as a top solution to reducing greenhouse gasses? https://drawdown.org/solutions/family-planning-and-education