Is cobalt the 'blood diamond of electric cars'? What can be done about it?

Electric cars are now the biggest driver of cobalt demand. Most of this is mined from the DRC, where working conditions are incredibly poor.

If you’ve got electronics with a battery – a mobile phone, laptop, water, or electric car – then there is a reasonable chance that parts of it were mined through the gruelling work of miners in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Cobalt has been in the spotlight in recent years – often called the “blood diamond of batteries”. The surge in electric vehicle sales has driven increased demand for cobalt. And most of the world’s cobalt is produced in DRC, often by unregulated, artisanal miners working under terrible conditions. Child labour is common.

Here I want to dig into these claims. What’s happening with the world’s cobalt? What role do EVs play? And crucially, what can be done about it?

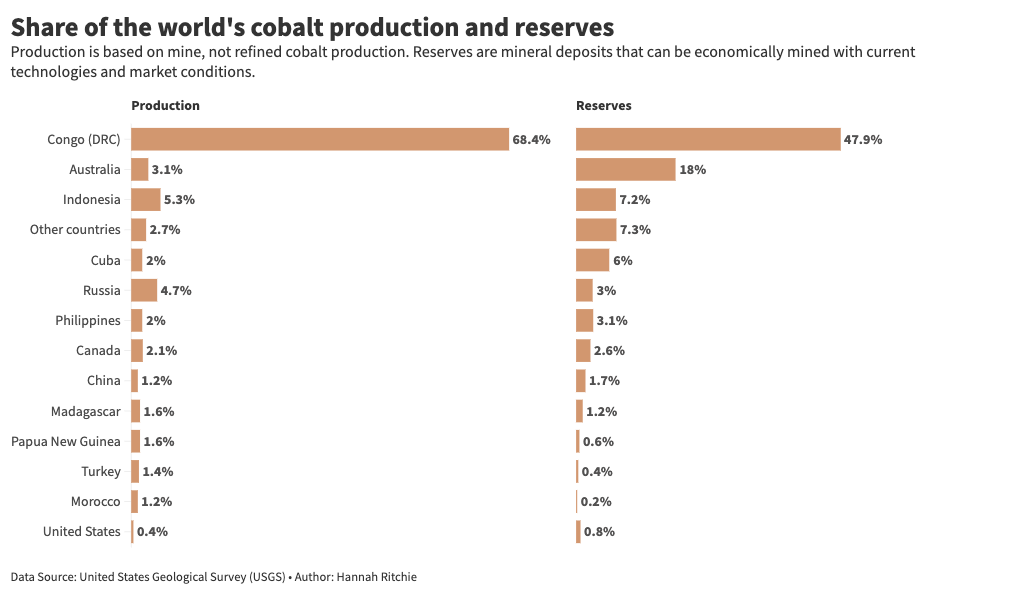

Global cobalt production and reserves by country

Almost 70% of the world’s cobalt came from the DRC (Congo) in 2022.1

In the chart below we see each country’s share of the world’s mined production, and reserves.2

DRC dominates, with 68% of production and 48% of the world’s reserves. Other notable producers include Australia, Indonesia, and Russia.

DRC doesn’t only have large amounts of reserves, they are also higher grade. Mineral ores tend to contain about 3% cobalt, compared to the global average of 0.6 to 0.8%.

How is global production changing over time? Are electric cars putting pressure on cobalt demand?

The short answer is yes: global production of cobalt has been increasing quickly and as we’ll soon see, most of this increased demand has come from batteries.

In the chart we see the change in global – and DRC – production since the late 1990s.

In the last decade, global production has doubled. Production rates have risen even faster in DRC. This means that DRC’s share of global production has increased. A decade ago it was mining half of the world’s cobalt; it now produces more than two-thirds.

In the chart below we see how the DRC’s share of global production has changed over time.

What is cobalt used for? Where does it go?

Cobalt is now in the spotlight for its use in electric cars. But cobalt was being used in various industries and products before the rise of EVs. It’s used in almost every lithium-ion battery, which means every mobile phone, laptop, tablet, bluetooth headphone, and electric toothbrush.

It’s not just batteries either. Cobalt is used for catalysts within the oil and gas industry, in car products such as airbags, paints, and various other chemical products. Cobalt is not just the “blood diamond of batteries”: it’s in the fossil fuel industry too.

The steep rise in cobalt production over the last few years has been driven by electric cars, though. In the chart, we see what the world’s cobalt was used for in 2021. EVs were the biggest user, consuming just over one-third. Batteries for other consumer products were not far behind at 31%.

But when we look at what has been driving growth in cobalt production in recent years, it’s nearly all batteries. 85% of cobalt growth from 2020 to 2021 was driven by lithium-ion batteries.

So, the data shows us two things. First, electric cars have driven much higher demand for cobalt. Second, most of this cobalt is mined in the DRC.

But is this a problem? What is life – and mining – like in the DRC?

Cobalt mining in DRC

The DRC is one of the world’s poorest countries. More than 60% live on less than $2 per day.3 80% do not have access to electricity, or safe drinking water.

Mining accounts for 90% of the country’s exports, and has vital source of income.

There are two forms of cobalt mining. Industrial mines are typically owned and run by international multi-corporations as formal operations. Working conditions are often poor, but are nonetheless run as legal operations with some safeguards in place.

Artisanal or small-scale mines (ASM) is when there is no formal employment in a mining company; individuals go out to mine minerals on their own.

It’s estimated that 10 to 20% of DRC’s cobalt is extracted from these artisanal mines. It could be as much as a quarter. In reality, the dividing line between industrial and artisanal mines is not clear-cut: you will often find artisanal miners digging close to industrial mines, sometimes feeding their cobalt into the ‘industrial chain’.

Nobody knows exactly how many people work in artisanal mining. Some estimate around 44,000. Others, up to 200,000. When we consider the family members that workers provide for, up to a million people could rely on it for their livelihoods.

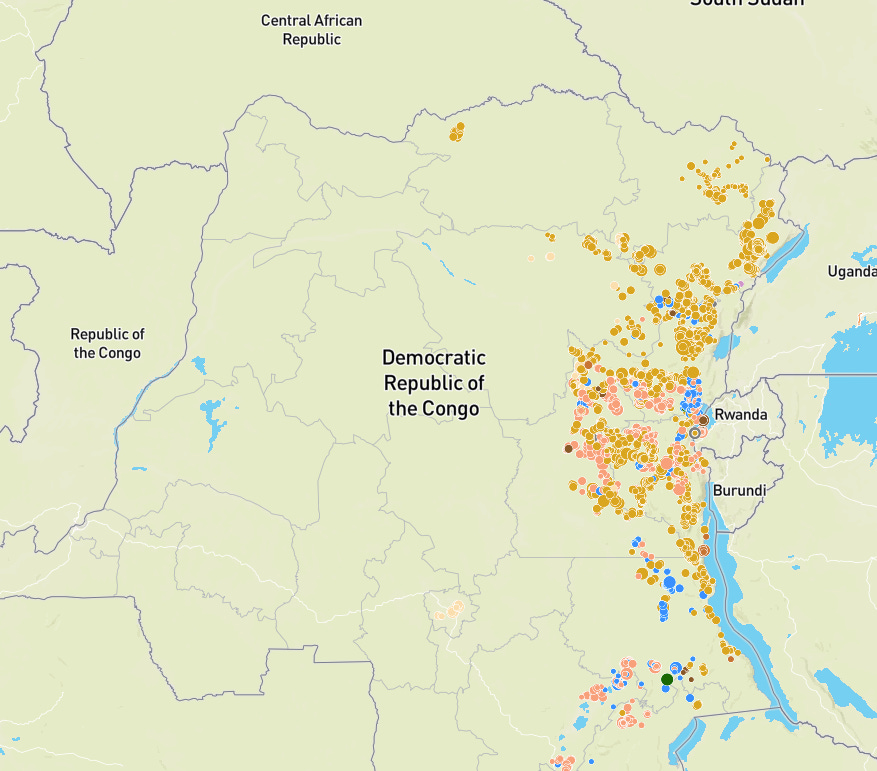

Cobalt is not the only form of artisanal mining in the DRC. The graphic below is from IPIS, which tries to map out where the country’s artisanal mines are [the interactive version is here]. Artisanal gold mining is much more common than cobalt.

But, the conditions of these two practices are not equal. Cobalt mining is more dangerous. Gold tends to be extracted from seams that are rarely more than one metre deep. Cobalt deposits can be 70 to 150 metres below the surface.4 It means moving entire blocks of rock at one time. There is always the risk of these deep mines collapsing. It’s not uncommon, and many Congolese workers have lost their lives.

As you might have guessed, the conditions of artisanal cobalt mining are awful. People do this back-breaking work for more than 12 hours a day. Injuries and fatalities from collapsing mines, or tumbling rocks are common. They’re exposed to chemical pollutants that lead to respiratory problems. Their eyes are often red or discoloured through exposure to toxic materials. In the following footnote, I will provide some first-hand accounts of what working in DRC mines is like.5

Child labour is common. Families often have to pay for schooling; inadequate public funding means that parents need to pay for the teachers themselves.6 Schooling can cost more than $5 per month. That might not sound like much, but it’s unaffordable for many families living in the depths of poverty. Not only is schooling expensive, children often need to work to bring in vital income.

The pay is extremely poor. A worker will typically earn a few dollars a day. Some earn $3 to $4 per day. For someone working 12 hours, that’s just 25 cents an hour.

Yet the harsh reality is that ASM is one of the best options people have. Remember that more than 60% live on less than $2 per day. Working in a cobalt mine could earn you more than most. That’s why so many people do it, despite the precarious working conditions.

Cobalt supply chain

If miners earn only a few dollars a day, what does the rest of the supply chain look like? How does cobalt go from the hands of a Congolese worker to the batteries in our phones or cars?

I’ve sketched the chain in the diagram below.

Artisanal miner: it starts with the miner who digs in the pits for a deposit called heterogenite, which is an ore of copper, cobalt, nickel.7

Negociant: artisanal miners usually then sell their sacks of ores onto a ‘negociant’. They are basically a middle-man between the miners and the depot that collects minerals collected across entire regions.

This results in a loss for the miners: they sell it to the negociant for a lower price than they’d get at the depot directly. Miners can’t take it directly because depots are too far away (and they have no form of transport) or they don’t want to buy a permit that’d needed to move ores across the country.Depot: the negociants transport sacks of ores, and sell them on to depots. These collect unprocessed ores across many different mining sites.

Processor / concentrator: Depots sell this to processors within the DRC. Since the ores are a mix of cobalt and other minerals, the cobalt needs to be extracted.

At this stage, artisanal ores are often mixed with cobalt from industrial mines.Commercial grade refiner: Cobalt is then exported to another country for refining. This transforms cobalt into a usable form for manufacturing. At this point, artisanal and industrial cobalt is mixed together: there is no way to differentiate where it came from.

Most of this cobalt goes to China. It processes three-quarters of the world’s cobalt. One Chinese company – Huayou Cobalt – produced 22% alone.

In his book, academic Siddharth Kara, asked officials why DRC didn’t refine cobalt itself. They said they didn’t have enough electricity to do so. As a result, DRC loses a lot of the potential value chain.Battery manufacturer: Cobalt is then combined with other metals to make batteries. The largest lithium-ion manufacturers are CATL and BYD in China; LG Energy, Samsung SDI, and SK Innovation in South Korea, and Panasonic in Japan.

These 6 companies made 86% of world’s lithium-ion batteries in 2021. CATL made one-third alone.Tech companies: Tesla, Apple, Microsoft, and other end use companies buy the batteries from manufacturers for their final products.

A few things become clear from this chain.

We start with many miners – all earning very little – and at each stage, the value becomes increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few companies.

Once cobalt is at the processing stage, there is no differentiation between artisanal and industrial cobalt. This is important for later: many companies claim that they do not use cobalt from artisanal mines, but this seems incredibly difficult to guarantee.

What have tech companies said about this? What are they doing?

In the last decade, big tech companies have been under pressure to address human rights issues within their cobalt supply chains.

Various companies made pledges to take artisanal mining out of their chains. Apple claimed it had done this in 2017. But, as we’ve just seen, this is incredibly hard to do. Artisanal and industrial cobalt is often mixed before it leaves DRC for refinement. Companies might do supply chain audits, but these only go so far. Indeed, a Wall Street Journal investigation in 2018 found holes in the assurance claims made by many tech companies. “Artisinal-free cobalt claims” turned out to be false.

This point was reiterated in a US lawsuit in 2019. The NGO, International Rights Advocates, launched a suit against Google, Apple, Tesla, Dell, and Microsoft, on behalf of Congolese families of children killed or hurt in the mines.

The companies did not face further action, because impacts in these mines could not be transparently linked back to them. As the judge put it:

“It might be true that if Apple, for example, stopped making products that use cobalt, it would have purchased less of the metal from Umicore, which might have purchased less from Glencore, which might have purchased less from CMKK, which might thus have instructed Ismail to stop purchasing cobalt from child artisanal miners, which might have led some of the plaintiffs to not have been mining when their injuries occurred.”“But this long chain of contingencies, in all its rippling glory, creates mere speculation, not a traceable harm.”

If it’s true in this direction – that harm could not be directly attributed to them – then the opposite is also true: there was insufficient evidence and transparency to fully absolve them of any harm.

Since then, some companies have taken action or made bold pledges to change.

Apple has pledged to only use recycled cobalt in its batteries by 2025. That would eliminate it from any new cobalt production.

And Tesla is no longer using cobalt in many of its new cars. In April 2022, it reported that around half of its new vehicles were using cobalt-free iron-phosphate (LFP) batteries.

What can be done? Ways to move away from DRC cobalt

We therefore have a problem. A low-carbon world is going to need more cobalt. A lot of that cobalt is coming from people (sometimes children) working under awful conditions.

What can we do about it?

Cobalt-free batteries

One option is to get rid of cobalt in our batteries entirely. Tesla has already made a move to cobalt-free batteries. How feasible is it for others to do the same?

It might not be too far off. Cobalt-free iron-phosphate (LFP) batteries are actually cheaper than conventional lithium-ion batteries. The biggest problem is that they have a lower energy density, which can have an impact on a car’s range. You either need to accept a smaller range, or a bigger and heavier battery. But, with the range of many EVs now going far beyond what any driver would need, small hits to a car’s range might not be a massive deal.

Sodium-ion batteries – which are cobalt-free – are also entering the race. These innovations have been spearheaded by Chinese manufacturers, but they’re already making their way into European markets: German automakers have already put their order in.Recycled cobalt

Apple’s approach to the problem is to simply recycle the cobalt from old phone and laptop batteries. If we could close the loop by recycling cobalt we’ve already extracted, then perhaps there would be no need for anyone to enter a cobalt mine again.

This might work for companies such as Apple, that have produced billions of phones and laptops. People are often replacing old products, rather than buying them for the first time.

This is not the case for electric cars, and larger batteries for energy storage. Most of the demand is coming from first-time buyers. The world is not close to being able to simply reuse cobalt from old EV batteries for new ones.

I have no doubt that cobalt recycling could play a large role in the future. But it will not solve the immediate problem for low-carbon tech. If we stick with lithium-ion batteries, the world will need a lot more cobalt than is available today.

Recycling is a future development that will make a difference, but it doesn’t address the immediate problem of Congolese children digging cobalt out of collapsing mines.

Source cobalt from other countries

The world needs cobalt, but maybe it doesn’t need to get it from the DRC.

As we saw earlier, there are various other countries, including Australia, Indonesia, Cuba, Russia, the Philippines, and Canada with reasonable-sized reserves.

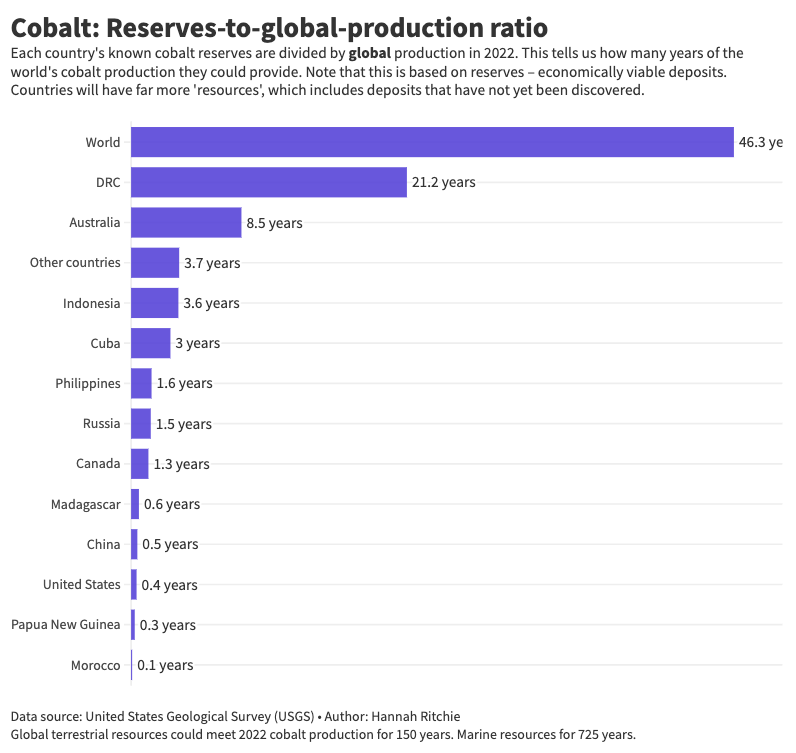

In the chart below I’ve shown the ratio of their reserves to global production in 2021. This tells us how many years of production they could meet with their current reserves.

One point to make clear: the world will not run out of cobalt. The world has about 46 years’ worth of known reserves. Those are deposits that are economically feasible with current technologies and markets. But when we take the world’s resources – that’s how much cobalt is there in total – we have more than 150 years on land, and 725 years on the ocean floor. Even then, those estimates will be conservative because we will probably discover more deposits as demand increases.

The same is true at the country level. Many countries will have known or unknown resources that they’ll find, or will become economically favourable later.

Still, looking just at known reserves, we can see that the DRC has the most by far – several decades’ worth. This is followed by Australia with around a decade, Cuba and Indonesia with 3 to 4 years, and the Phillippines and Russia with a few years.

It’s not out of the question that other countries try to ramp up their cobalt production. Maybe this will make some dent in global demand. But it seems much more likely that companies would switch to non-cobalt alternatives than source most of their cobalt from elsewhere.

The damage of moving away from DRC-sourced cobalt

I can see why many companies would want to move away from cobalt completely. They have (rightly) come under fire for their involvement in human rights’ abuses. Every time EVs are mentioned, someone raises the criticism of child labour and human exploitation.

It is probably easier to take cobalt out of their supply chains than to track and reform all of their sourcing strategies. Even if they could transparently trace all of their cobalt back to the source, they’d still have the association that “cobalt = exploitation” attached to their name.

The solution seems simple. Cobalt mining is bad, so stop cobalt mining.

But, the overall problem is a bit more complex. If the world was to turn its back on DRC cobalt completely, it would have negative consequences for the country. Mining – whether industrial or artisanal – is a vital source of income for many.

There’s no denying that the working conditions are terrible, and the pay is incredibly low. But the harsh reality is that those working in cobalt mining earn more than most in the DRC. Remember, more than 60% of the population lives on less than $2 per day. Artisanal miners usually earn a few dollars more. If these industries were to disappear, more people would be pushed below the international poverty line. Child labour could increase as poorer households can no longer afford to send them to school.

Most NGOs and researchers in this area strongly recommend that companies do not simply move away from DRC cobalt. Amnesty International – which did some of the initial investigations into the human rights’ abuses in cobalt supply chains – states clearly that the solution is not for companies to stop using DRC cobalt, or to ban artisanal mines.

Instead, it calls for much more pressure on suppliers and refiners to track and disclose the sources of their cobalt. Without this information, manufacturers and companies further downstream cannot properly audit their supply.

This will not be a simple or easy process, hence why many companies will prefer to move away from cobalt entirely.

But it would be a shame if the DRC could not turn its cobalt stocks into economic benefits for some of the world’s poorest people.

If you want to read more about the cobalt industry in the Democratic Republic of Congo, I highly recommend Siddharth Kara’s book: Cobalt Red.

This data comes from the United States Geological Survey (USGS): https://www.usgs.gov/centers/national-minerals-information-center/cobalt-statistics-and-information

Reserves are mineral deposits that can be extracted using current technologies and are economically viable under current market conditions.

This is not the same as 'resources', which also include known and unknown deposits that are not currently viable but could be in the future.

This is measured using the International Poverty Line, which was recently adjusted from $1.90 to $2.10 per day.

Crundwell, F. K. et al (2011). Production of cobalt from the copper–cobalt ores of the central african copperbelt. Extractive metallurgy of nickel, cobalt and platinum group metals, 377-391.

Miner 1:

“The danger is always the wall. You never know when rocks will fall or the mine will collapse. So far my team has been lucky, but I don’t know how long that luck will last. I have nightmares when I sleep about that wall trapping me, crushing me.” Community Respondent 29 noted that he always “felt sick and scared of accidents. One of my diggers was in a hole, and a stone fell and crushed him. He lost both his legs.”

Miner 2:

“I know of many friends involved in accidents. We have avoided them on our team but not because we are better or worse, we are more or less careful, have better or worse equipment. We have just been lucky, that is all, and some day our luck may change.”

Expert 1:

"Proximity is the problem. People migrate and settle literally on top of the mine. When landslides happen, homes and walls crack and fall apart, people are injured by projectiles."

From this study: Sovacool, B. K. (2019). The precarious political economy of cobalt: Balancing prosperity, poverty, and brutality in artisanal and industrial mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Extractive Industries and Society, 6(3), 915-939.

This is documented in Siddharth Kara’s book, Cobalt Red.

Only around 2% of the world's cobalt is from direct cobalt mining. Most cobalt is a byproduct of mining for nickel and copper too.

I think it's worth mentioning what one European company is doing: Fairphone.

They have joined the Fair Cobalt Alliance to improve the cobalt supply chain, especially in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)

https://www.fairphone.com/en/2020/08/24/be-part-of-the-change-join-the-fair-cobalt-alliance/

Website of the Fair Cobalt Alliance with their steering committee members (with a representative of Tesla too): https://www.faircobaltalliance.org/about-us/governance/

If you asked the miners in the DRC what we should do about conditions in the cobalt industry, I don’t think they would say “please boycott our country and put us out of a job”. It would be great to improve conditions in the DRC but it seems like to do that, we should help their economy, rather than boycotting it.