How many people died from disasters in 2023?

More than usual, with most lives lost in devastating earthquakes.

If you don’t look at disaster statistics on a semi-frequent basis, it’s impossible to know how many people die in disasters each year.

Following the news closely doesn’t always help. Are more people dying from disasters, or are you just paying more attention?

Thankfully there is an invaluable project – EM-DAT – that builds a database of events across the world.

It recently published its annual summary of disasters in 2023.

I’ve been exploring the data to understand the toll of last year and thought you might like to follow along.

Earthquakes dominated disaster deaths in 2023

EM-DAT estimates that just over 86,000 people died in disasters in 2023.

More than 70% of these deaths happened in earthquakes. You can see the breakdown in the chart below.

The massive earthquake that hit Turkey killed more than 50,000. Earthquakes in Syria, Morocco, and Afghanistan killed another 10,000 combined.

The other major event was Storm Daniel, which caused torrential rains and collapsed two dams in Libya. More than 12,000 people died (the exact death toll is still uncertain).

I think the total death toll could rise to over 100,000 when more complete estimates of heatwaves are reported – you’ll see that I’ve marked them as “incomplete” on the chart. More on this later.

EM-DAT provides a useful list of the 10 most fatal events in 2023.

If there’s one key insight from this year’s data, it’s that the world is still extremely vulnerable to earthquakes. As we’ll soon see – almost any year with an extremely large death toll – has at least one major earthquake.

We’re not completely helpless to earthquake activity, but it does require large investments in seismic-proof infrastructure and strong governance to make sure that building codes are upheld.

Last year I wrote an article in the Washington Post looking at data on earthquake fatalities in Turkey, Japan, and Chile. The main point was that Turkey could have saved many thousands of lives if it had upheld its quake-proof building codes. Failure to do so made last year’s disaster far more devastating than it needed to be.

What percentage of global deaths were caused by disasters?

Around 58 million people die every year (here I’m using data for 2019 – death tolls in 2020 and 2021 were higher due to Covid-19). 86,000 is around 0.2% of 58 million.

So, disasters are responsible for around 0.2% of all deaths. Note that this is a crude way of comparing these numbers: a 90-year-old dying from heart disease is not the same as a child – with 80 or more years ahead of them – dying in an earthquake.

The fact that its share is small shouldn’t underplay the tragedy or importance of these deaths. The main point of my Washington Post article on Turkey is that many of these deaths could have been prevented. Thousands of people were let down and deserved better.

The same is true in Libya: the dams in Derna were not maintained, and leaders had been warned that there was a high risk of failure during periods of heavy rain.

2023 was the most fatal year in a relatively safe decade

How did 2023 compare to previous years?

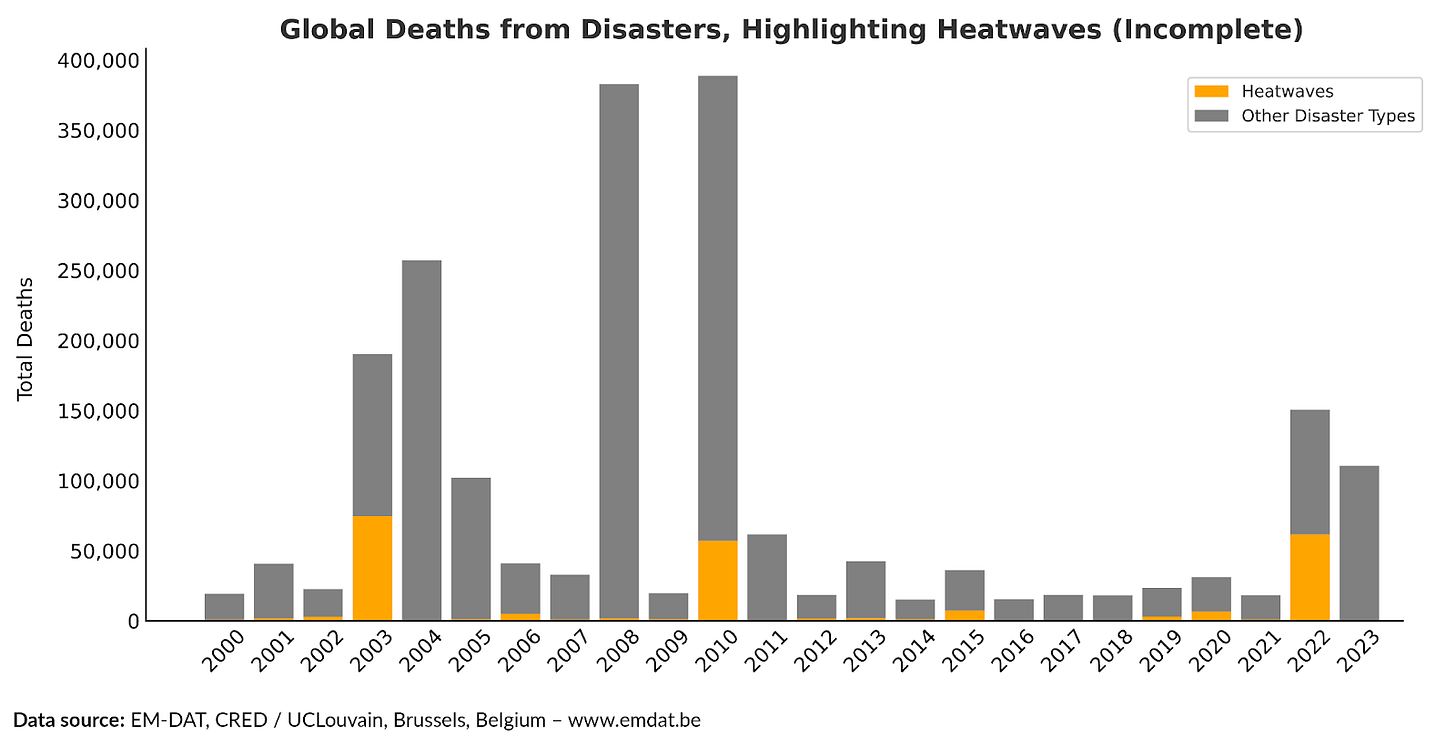

I’ve plotted the annual total since 2000 in the chart below.1 Here is an interactive chart if you want to explore the data.

You can see that the decade prior to 2022 and 2023 was a relatively “safe” one. In most years, the death toll was between 10,000 and 20,000. This is still far too many, but is low by historical standards.

You will notice that the multi-decade trend is interrupted by large spikes in mortality. This is almost entirely the result of large earthquakes. In the chart below, I’ve highlighted deaths from earthquakes in red.

In 2004, there was the Boxing Day tsunami that hit Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and several other countries in the region. In 2005, a large earthquake hit Pakistan. In 2008, a quake hit Sichuan in China, killing almost 90,000. Haiti was struck in 2010. And in 2011, there was the Fukushima-Daiichi earthquake and tsunami off the coast of Japan.

Earthquakes had been relatively quiet for the next decade.

To see how deaths from other disasters have changed, let’s remove earthquakes completely. The new trend is below.

What explains the other big jumps?

The massive event in 2008 was Cyclone Nargis, which hit Myanmar and killed almost 140,000.

The other outlier years – 2003, 2010 and 2022 – all had severe heatwaves in Europe. That brings us to the topic of heat deaths, which is a bit more complicated.

Incomplete data on heatwaves and temperature-related deaths

The chart below highlights reported heatwave deaths in the dataset.

The figures for heatwave deaths in 2023 are not final. The latest estimate from EM-DAT is just over 400, but this is too low. EM-DAT notes this too, and expects that the toll will rise as more data comes in.

Heat-related deaths are harder to estimate than deaths in an earthquake or a wildfire. That’s because most people who die from extreme heat don’t pass out and die from heat stroke, as we might imagine. Instead, exposure to sub-optimal temperatures puts our body under stress and increases our likelihood of dying early from conditions such as cardiovascular or kidney disease, respiratory infections, or diabetes.2

Researchers need to estimate these deaths afterwards using a range of statistical methods. They can, for example, look at excess deaths – how many more people died in a given month or year versus what we would expect in a “normal” year. Or a method called the “Minimum Mortality Temperature” (MMT), where they build statistical models of how mortality rates change with temperature.

That’s all to say that it takes time to calculate these estimates, so there is often a lag. We are still waiting for comprehensive reviews from organisations like the European Mortality Monitoring (EuroMOMO) portal.

EM-DAT notes that for 2022, it recorded 16,000 heatwave deaths in Europe based on preliminary data, but subsequent revisions later in the year pushed this figure up to 61,000. I expect that the same will happen this year: once complete estimates have been established for 2023, the heatwave death toll will increase a lot from 400 to tens of thousands.

But, the lag in these estimates is not the only problem.

First, most countries don’t report heatwave deaths at all. The EM-DAT database almost exclusively records estimates from Europe. I think a handful of other countries – such as the United States – are included, but often have low mortality because most households in America have some form of air-conditioning.

But are we really saying that no one in South America, Africa, and Asia dies from extreme heat? Seems unlikely. Yet, most countries in these regions are completely missing.

To be clear, this is not EM-DAT’s fault. They can only report statistics that are available.

Second, there is no universal standard for how to estimate heat-related deaths. There can be large differences in the final estimates depending on which methodology is used. This makes country-to-country consistency hard but also makes it hard to track deaths over time. Our registration systems and statistical methods have surely improved since 2000, which affects comparability over time.

Third – and this often sparks a lot of controversy – these datasets don’t include deaths from cold temperatures. This matters. In many countries, more people die from cold than from heat.

Research groups that try to estimate the total mortality impact of ‘sub-optimal’ temperatures find that hot and cold conditions cause between 1.7 to 5 million premature deaths a year.3 Again, this is usually not equivalent to a 10-year-old dying in an earthquake; it’s usually older people dying months to years earlier than they would have otherwise. But this matters.

What’s consistent among these studies is that “cold” kills more than “heat” in every country. What’s important is that most people are often not dying from extreme cold. They die prematurely from exposure to “moderate cold” which in many countries is not that cold at all: in the UK, this could be around 10°C, for example.

If we zoom into the UK, we can find this result from the government. With growing (and very valid) concern about the increased health risks of heatwaves, its Office for National Statistics uses optimal temperature models to estimate deaths on the coldest and hottest days. In all parts of the country, at least twice as many people died from cold as from heat.

Again, this is not to undersell the huge health impacts of heatwaves – which will only increase with climate change – but it makes it adds complexity to disaster statistics that only include deaths from heatwaves (and inconsistently across the world).

To take these risks seriously, we need consistent and harmonised ways of quantifying these deaths, and we need to make sure that they’re being reported across all countries, not just the richest.

The preliminary estimate of disaster deaths in 2023 from EM-DAT is 86,000. But I expect that later in the year, this figure will be pushed higher once improved estimates of heatwave deaths are reported. A figure over 100,000 is not implausible.

EM-DAT suggests that data from 2000 onwards has enough coverage to make it relatively comparable. Some events are missing pre-2000, so figures in the 20th century are probably underestimated.

https://doc.emdat.be/docs/

Benmarhnia, T., Deguen, S., Kaufman, J. S., & Smargiassi, A. (2015). Vulnerability to heat-related mortality: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiology.

Burkart, K. G., Brauer, M., Aravkin, A. Y., Godwin, W. W., Hay, S. I., He, J., ... & Stanaway, J. D. (2021). Estimating the cause-specific relative risks of non-optimal temperature on daily mortality: a two-part modelling approach applied to the Global Burden of Disease Study. The Lancet.

Zhao, Q., Guo, Y., Ye, T., Gasparrini, A., Tong, S., Overcenco, A., ... & Li, S. (2021). Global, regional, and national burden of mortality associated with non-optimal ambient temperatures from 2000 to 2019: a three-stage modelling study. The Lancet Planetary Health.

Wu, Y., Li, S., Zhao, Q., Wen, B., Gasparrini, A., Tong, S., ... & Guo, Y. (2022). Global, regional, and national burden of mortality associated with short-term temperature variability from 2000–19: a three-stage modelling study. The Lancet Planetary Health.

Most global studies estimate that ~9 times more people die from extreme cold than extreme heat. It follows that warming will reduce deaths from extreme temperatures.

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(23)00023-2/fulltext

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(21)00081-4/fulltext

Indeed this has been reported for the UK for the period 2001-2021, during which 500,000 lives were saved by warming!!!

https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/articles/climaterelatedmortalityandhospitaladmissionsenglandandwales/1988to2022

There was a furious reaction to the initial report and the ONS were forced to revise it to disguise this inconvenient fact. It can be seen if you look at the data but was erased from the summary section.

What these data show is that we should focus more on preventing deaths from extreme cold as well as extreme heat. This involves better housing and accessible and affordable energy, especially electricity.

Any measures that decrease economic growth and/or decrease the affordability/availability/reliability of electricity will increase deaths from extreme temperatures.

We need to bear this in mind when we reduce emissions!!!

I think the flaw in this is looking at deaths from shocks rather than suffering from stressors. At the moment the latter is the far more serious consequence of climate change and has significant geopolitical consequences (if the human suffering alone is not a good enough reasons to be deeply alarmed). What really matters is numbers of people displaced, on the move, livelihoods destroyed etc etc etc