The end of range anxiety: how has the range of electric cars changed over time?

The average range of electric cars has more than tripled since 2011.

If you’re looking for an electric vehicle today, you have a menu to choose from.

From small, two-seater convertibles to large four-wheel drives. From small-battery city drives to long-range country-wide rides.

This is a dramatic transformation from the market a decade ago. Then, there were just a handful of car models, and small-battery city drives were your only option. Going further than 50 miles was a precarious mission to map out the charging points along the way. And those chargers were few and far between.

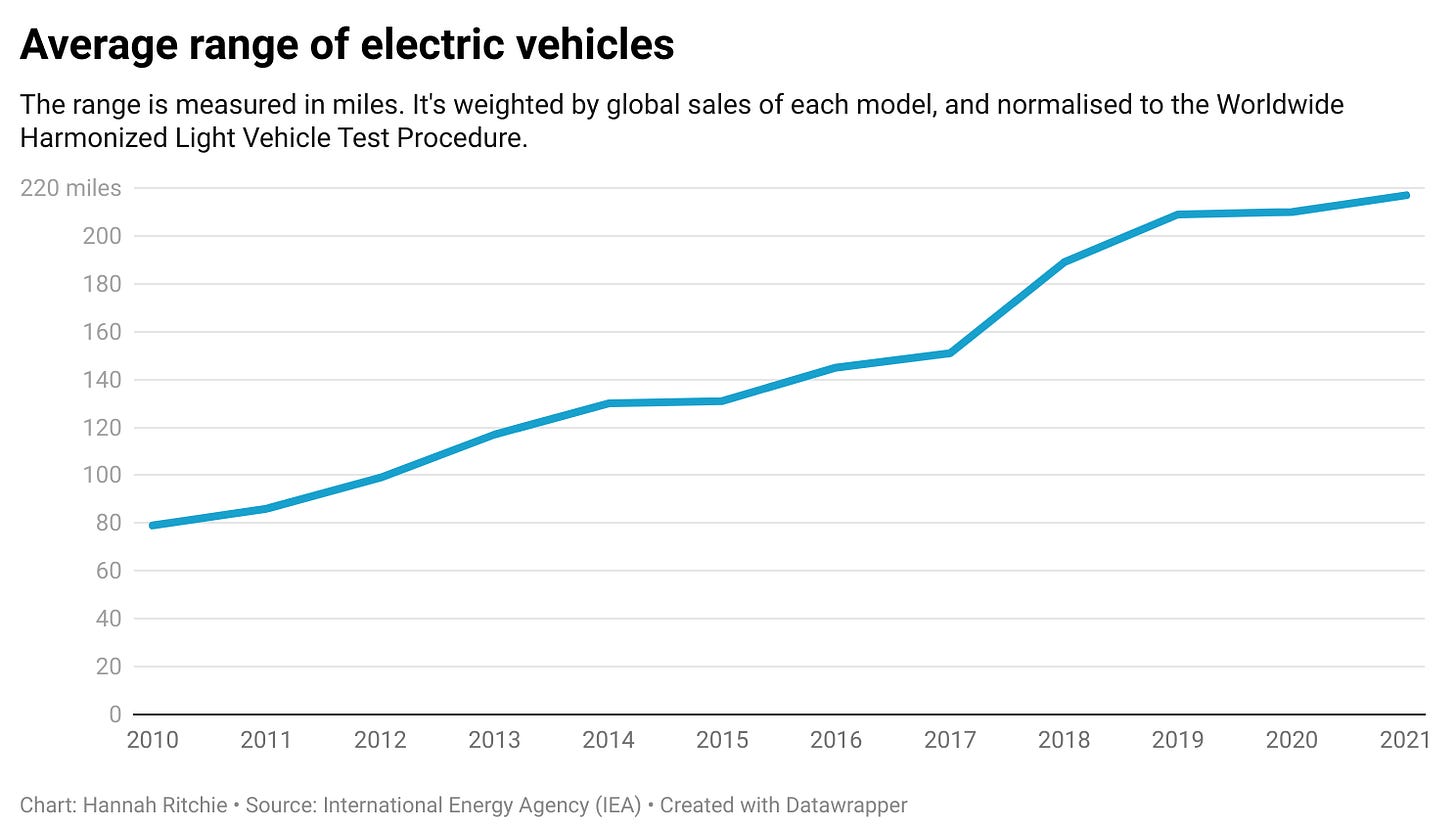

We can see how the electric vehicle market has changed from a simple line chart of their average range. This data comes from the International Energy Agency (IEA): each car is weighted by its global sales, so a top-selling car’s range is better reflected in the average.1 We can see that the average range has almost tripled. In 2010, it was just under 80 miles. By 2021, it was hitting 220 miles.

This is much further than the average car drives on most days. In the UK, drivers cover around 20 miles per day (this is even less if a family owns a second car).2 Most people’s range anxiety isn’t about day-to-day driving: it’s about those rare long trips for a holiday or special occasion.

The evolution of the average range of EVs misses lots of information about how the electric car industry has changed. It doesn’t show us the distribution of cars on the market – from the lowest to maximum range – or the number of them.

Let’s take a closer look now.

Electric cars can travel much further, and companies want a piece of the market

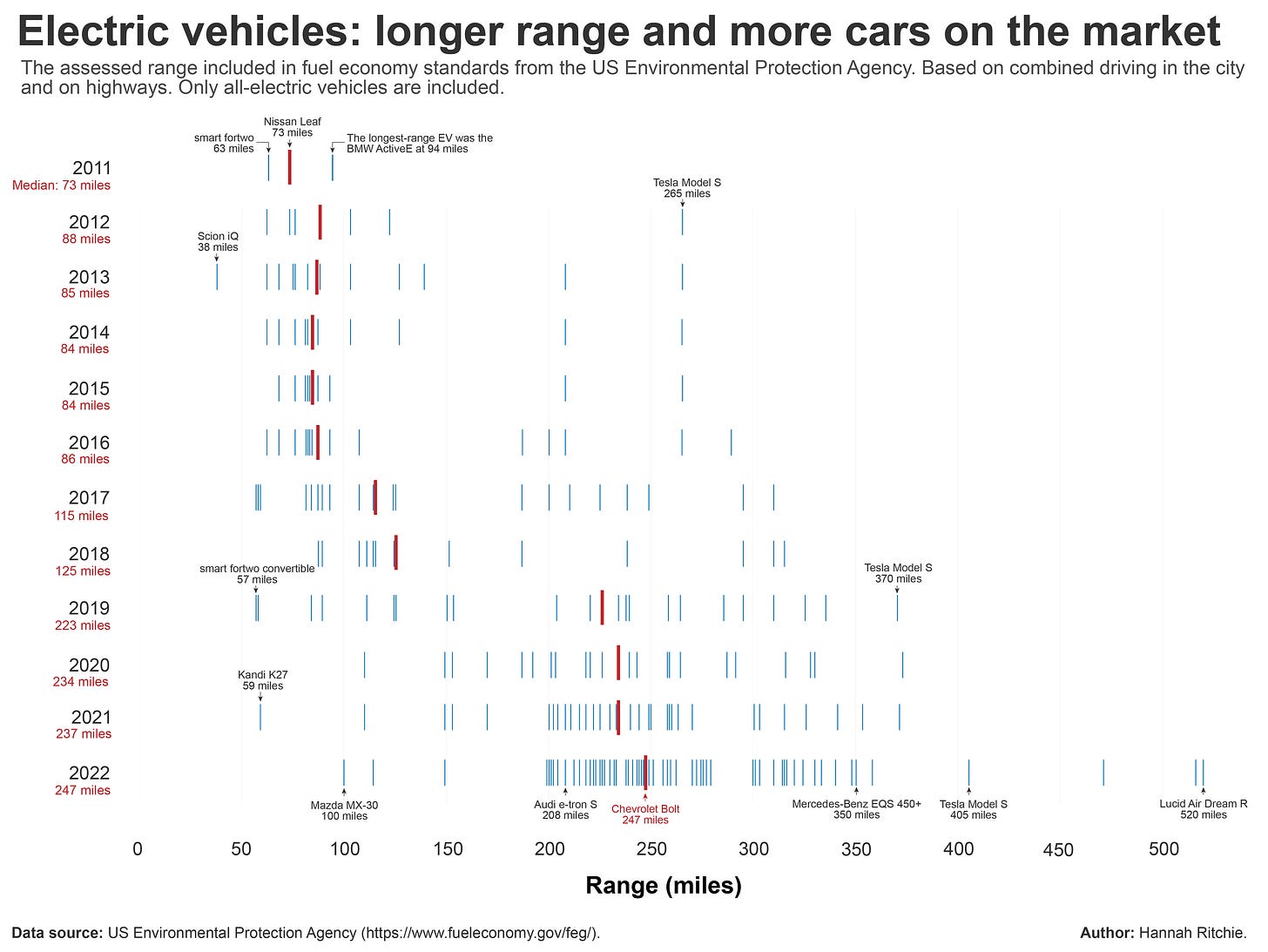

Rather than looking at the average range, I’ve plotted the entire distribution of electric cars on the market. This is shown in the chart below.3 I’ve only included all-electric vehicles, so hybrids are not included.

Each year has a series of lines – shown in a barcode format – where each line represents one car model. Their position on the x-axis is their assessed range (measured in miles): cars further to the right can travel further on a single charge. This range is the combined rating for city and highway driving; you can usually get in some more miles if you’re only driving in the city.

This lets us see the full span of vehicles on the market, from the shortest to the longest range. It also lets us see the number of different models that are available.

The median range is shown in red. This will not be the same as the IEA average numbers that we saw before, because these are not weighted by sales.

There are a few things that jump out.

The median range of EVs has increased 3.5-fold since 2011. You can see the median increasing as the red line shifts further to the right. The mid-range car in 2011 was the Nissan Leaf, where you could get 73 miles on a single charge. In 2022 this was the Chevrolet Bolt, at 247 miles.

Your options were really limited in 2011. There were just three cars in the EPA reports: the smart fortwo, the Nissan Leaf, and the BMW ActiveE. Today there are more than 70 models. The EV database, which has current and upcoming cars, now has more than 187.

It’s not just the average that has increased a lot: the whole distribution has shifted to the right, and the maximum range we can get from EVs is more than five times what it was. For years Tesla has taken the top spot for the longest-range cars. But in 2022, it was knocked off by the luxury Lucid Air Dream R.

That has been an important development overall: for years, EVs were a gimmicky niche. They didn’t look cool and they were more expensive than petrol or diesel.

The EV market has evolved to cater to all tastes. There are cheaper, smaller EVs designed for city driving alongside long-range, luxury cars for the rich.

All of these developments have happened while their prices have tumbled. As I wrote about previously, the battery in a Tesla alone would have cost up to $1 million in the 1990s. Now, they are competing with petrol and diesel on cost (and will soon overtake them).

These factors combined are why I predict the transition to electric cars will happen much faster than people expect.

Methodological notes

The ratings are given as the combined range for city and highway driving. You tend to get more miles in city-only driving. If you’re mostly driving on highways, the range will be a bit less than these figures.

The specific range you’ll get depends on other conditions such as temperature, weather and the efficiency of driving style. The economy of a battery (just like with gas cars) tends to be poorer in colder weather.

Here I’ve used all-electric cars on the market in the US. It may be missing models sold in other countries.

I've converted it from kilometres to miles so it's in the same units we'll use later on.

The average distance travelled per year is around 7,000 miles. This works out at around 20 miles per day.

Of course, this does not mean that people travel 20 miles every day.

Here I'm using data from the US Environmental Protection Agency's Fuel Economy Standards reports.

Each year it publishes a report detailing the characteristics and standards of every car on the market; for all types of vehicles, not just electric ones.

I’ve read recently that the cost of removing CO2 from the air is about $600 per ton and that this cost is projected to go down significantly, perhaps to $100 per ton. So I asked myself what is the trade between an EV and an ICE with equally clean air. At 7,000 miles per year as assumed in this article I think an ICE produces about 3 tons of CO2 per year. An EV produces about 5 tons more CO2 to manufacture than an ICE and costs more, say $20,000 for arguments sake. If I’ve got this right then the break-even cost for equally clean air takes about 12 or 13 years at current CO2 clean up costs.

Acquiring and improving clean up technologies could help with other sources of CO2 such as a rocket launch which produces as much CO2 as 395 transatlantic flights.

Saw YouTube video of cold performance and how much Tesla trip planner really alleviates this concern. I have a 2014 PHEV with tiny battery and lack of triplanner is noticeable as it is too much mental effort to try and keep battery charged when running errands (current 10 mile range with over 100,000 miles on the car) It is amazing to me that some cities charging infrastructure is getting so good and range is so good even someone who has an apartment could realistically have an EV without much inconvenience.