If the UK has lots of renewables, why do electricity prices follow gas prices?

Electricity prices are set by the most expensive source that needs to be ‘turned on’ at any given time – that’s usually gas.

When gas prices hiked up last year, electricity prices in many countries did the same. It’s obvious why the gas for heating in your home got more expensive, but why did electricity?

After all, the UK and many countries across Europe now have a good amount of renewables on the grid. Once a wind or solar farm is built, the operating costs are very low. Why were they not pulling a strong lever on the electricity market, instead of gas?

For those that are a bit confused, I want to give a very simple overview of what’s going on.

It’s the wholesale costs of electricity – not green taxes – that are driving the price hike

First, a quick clarification on what has driven the increase in energy bills in the last few years.

It has, almost entirely, been down to an increase in wholesale energy prices – the generation costs. In the chart below we see the breakdown of the capped price offered in the UK. You can see that the massive increase in 2022 is wholesale costs (shown in blue).

Green levies are now a small percentage of consumer bills. So are supplier profits.

While some people – including the UK’s former prime minister, Liz Truss – proposed solutions such as ‘getting rid of green levies’, this would not make much of a difference to consumer bills. It’s the wholesale price of electricity that’s responsible for high prices. Let’s look at why.

In many electricity markets, the price is set by the most expensive source that has to be “turned on”

Countries can price their electricity markets in a range of different ways. What I’m going to describe here is what’s called ‘marginal pricing’ or ‘marginal sourcing’. It’s a common pricing model, and the one that’s used in the UK. Here, when I mention the UK I’m technically talking about Great Britain: Northern Ireland has a different system.

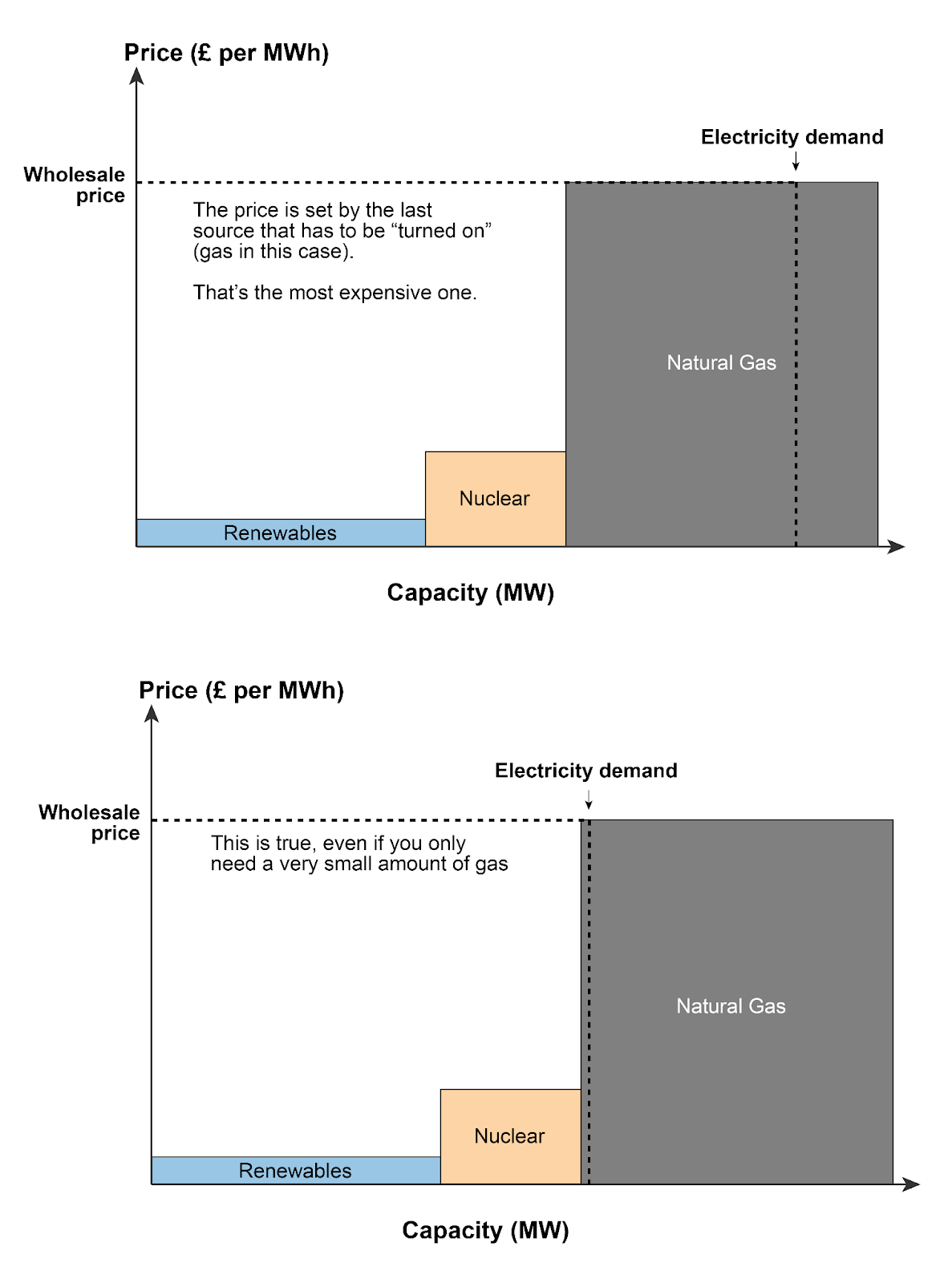

Let’s say we have three sources of electricity on our grid: renewables (solar and wind), nuclear, and natural gas. We’ll lay them out side-by-side, from the cheapest on the left to the most expensive on the right. This is shown in the diagram below.

The width of each box is how much of that source we have. And the height is the price it takes to generate one unit of electricity.

It costs very little to produce solar and wind, whereas coal or natural gas can be expensive because you have to buy the fuel to keep the plant running.

Note that this is a very simplistic diagram of the electricity mix – in reality, there will be different prices within each box. The price of generating gas will vary by power plant due to factors such as age, efficiency, and technology type. Each box is more like a staircase, rather than a rectangle.

Here we’re focusing on wholesale or electricity generation costs, not final consumer costs which include other things such as transmission costs and taxes.

The day before the market ‘opens’, producers will say how much it’ll cost them to produce a unit of electricity. The way it works is that the cheapest producers go to the front of the queue; so renewables come on first. Then the next cheapest, and so on.

But the final electricity price on the market is set by the most expensive source that has to be “turned on” to meet demand. This is called the ‘marginal price’ since it’s the marginal source of electricity that sets the price.

So, let’s add a line to our chart that shows how much electricity the country needs (our demand).

In the situation below, there aren’t enough renewables and nuclear to meet our demand. So, natural gas has to be turned on. This means the price of electricity is set at the generation cost of gas. This is still true – as shown in the bottom diagram – if you only need a small amount of gas. It’s the marginal source, so it sets the price. In this situation, the price of renewables and nuclear is irrelevant.

Now, the width of the boxes, and the demand line will change over the course of a day. You might get more solar during the middle of the day; or a windy few hours. And you will get peaks in demand in the morning and early evening when people start to use more electricity. So this trading – and price-setting – happens every half hour.

Let’s think about what happened when the price of gas shot up in 2021/22. Imagine we had the same sources, and the same demand as above. The cost of generating gas for producers increased because they had to buy more expensive gas on the market.

This means the ‘marginal cost’ of electricity in our grid increased too because it set the wholesale price.

The UK nearly always has some gas in its electricity mix

The problem for the UK is that it nearly always has natural gas in its mix. This is sometimes not much – occasionally reaching as little as 10%. But, as we know, even a little gas means it sets the price. You can see what sources as being used in the UK on an hourly basis here.

This paper – The Role of Natural Gas in Electricity Prices in Europe – looked at what sources were setting the price across various European countries.1 This is shown in the chart below from 2015 to 2021.

You can find the UK in the bottom-right corner. The researchers estimated that gas (in orange) was the ‘marginal’ source, determining the price 98% of the time in 2021. This was despite the fact it only produced 40% of its electricity across the year.

Lower demand, or more renewables and nuclear would have lowered prices

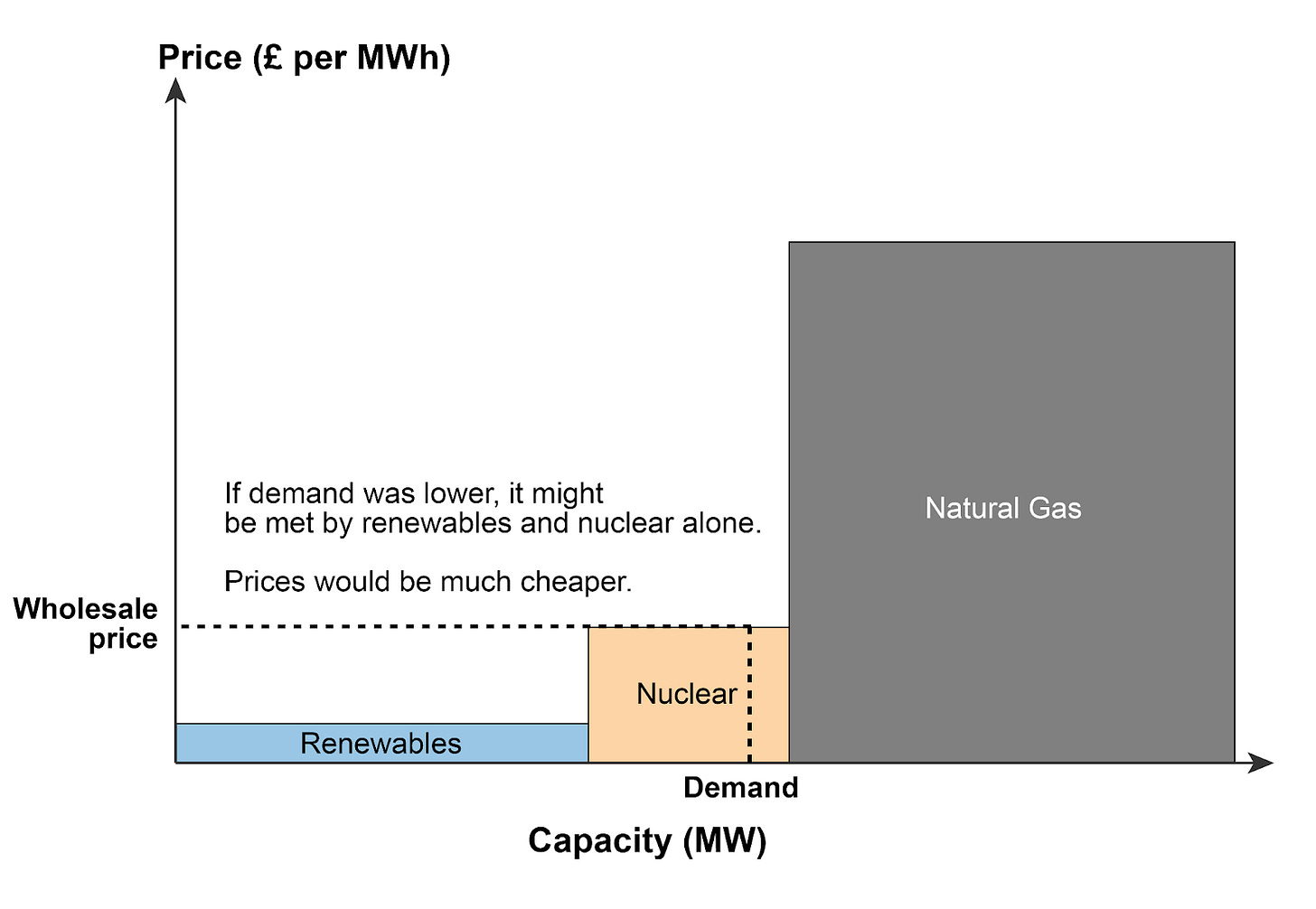

To have low prices in these examples, we need to avoid turning gas on. How do we do that?

If demand was lower, renewables and nuclear might be able to meet it on their own. This is shown below.

Or we could increase the supply of renewables and nuclear. If we had more renewables they might be able to cover demand for more hours of the day, and we’d rarely have to turn our gas plants on. This is shown below.

The problem, of course, is that renewables often need some backup to balance out the times when they’re not generating e.g. if you have a low or no-wind day. So even if you had lots of wind power, there might be times when generation is low and you still have to turn the gas on. That’s why having other forms of energy storage is important.

This pricing structure is not unique to electricity markets

You might think that this is a stupid way of pricing electricity. But there’s nothing unique about this system: it’s how most commodity markets work. It’s just a simple demand-supply curve from Economic 101.

The market dynamic is the same across many products: wheat, oil, nickel, cotton etc.

While this setup might not produce the outcomes that we want or need, it is working in the way that it was intended to.

There are some obvious problems with this pricing system, which I’ll come on to. But it does have some benefits.

The first plus point is that it is ‘efficient’. The cheapest sources of electricity come online first, and the most expensive go to the back of the queue. It also means that our low-carbon energy sources – renewables, then nuclear – are used first, and fossil fuel plants are used as little as possible; only when they’re needed.

The second is that low-carbon electricity producers can often start to recover their up-front costs, and make further investments in renewable energy projects. In the examples above, solar and wind producers are generating electricity at very little cost, then they’re selling it on the market at the much higher price of gas. These profits can then be used to recover the up-front costs of installing the plant. This is partly impacted by a scheme called ‘Contracts for Difference’ in the UK – I’ve provided details of this in the footnote if you’re interested.2

The downsides to marginal pricing systems

There are some obvious challenges.

First, electricity prices are essentially ‘coupled’ with natural gas prices. This means countries – and their consumers – are at the whims of international fossil fuel markets. It’s hard to shield people from volatile changes in prices.

Second, the cost benefits of renewables are not properly passed on to consumers. This is not only important from a monetary perspective, but also an optic one. It makes little sense to people that electricity prices are so high when governments tout how much cheap renewables they’re adding. Some people think that it’s renewables that are pushing prices up (which is not the case with the rise over the last few years).

Third, ‘electrify everything’ lies at the heart of decarbonising our economies. We want transport to go electric. We want to move from gas boilers to heat pumps (powered by low-carbon electricity). To make this move attractive and viable, we cannot have high electricity prices. It reduces the economic benefits of moving to electric cars or installing a heat pump. High gas prices should incentivise people to move from gas boilers to low-carbon heat pumps, but this is not the case (if anything, the opposite is probably true).

There are other reasons why electricity prices are so much more expensive than gas prices. This is mostly down to the fact that most taxes and levies are placed on electricity rather than gas and petrol. But that’s a discussion for another time.

The main point is that as long as electricity prices are coupled with gas, they will be volatile (and often high). This erodes a lot of the economic benefits for consumers of ditching their petrol cars and gas boilers for electric equivalents.

The UK has said that it will review its electricity market system – if and when another model might be adopted is still not clear.

In a future post, I might look at what the alternative options might be.

Zakeri, Behnam and Staffell, Iain and Dodds, Paul and Grubb, Michael and Ekins, Paul and Jääskeläinen, Jaakko and Cross, Samuel and Helin, Kristo and Castagneto-Gissey, Giorgio, Energy Transitions in Europe – Role of Natural Gas in Electricity Prices (July 23, 2022). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4170906

You might have heard of the scheme ‘Contracts for Difference’ (CfD) in the UK. It has been the UK’s main program to incentivise investments in low-carbon electricity and is built on a similar premise.

It works by agreeing on a ‘minimum’ price (the ‘strike price’) that a renewable energy producer will be paid for the electricity on the market. The point of it is to give investors the security that electricity prices will not go too low for them to recover their initial up-front costs.

So, imagine that to break even over its lifetime, a wind farm would need to be able to sell its electricity for £50 per MWh. If electricity markets are volatile, and prices drop below £50, then the wind farm is in trouble. CfD ensures that the wind farm will not get paid less than £50 per MWh; if prices drop below this level then producers will be given a top-up payment. This money comes from a levy placed on all electricity suppliers. The opposite is also true: if the market price is higher than the strike price, then the producer pays the surplus back.

During this period of high prices, some of the payments ‘made back’ to suppliers from renewable generators on CfD contracts have been fed back to consumers.

This article could lead readers to conclude that we can decrease electricity prices by installing more wind and solar. This would be the opposite of the truth. In ALL countries where intermittent renewables have been installed electricity prices INCREASE. This increase is exponential rather than linear.

The reason for this is the very high cost of dealing with intermittency. Essentially one either needs to operate two electricity generating systems with the dispatchable one on permanent standby, or one has to have high capacity electricity storage systems, which are extremely expensive.

This is only part of the story. Your second footnote starts to explain the rest, but is not complete. Most of the offshore wind CfDs prices are far higher than £50/MWh. Some are over £200 in today's terms. Today's price on Trading Economics is £105/MWh. And of course they are index linked so go up each year with inflation. So even though the wind farm gets paid £105, we pay over £200 in our bills. I have solar panels on my roof from 2010 and now get paid over £600/MWh generated. This partly explains why electricity prices have not fallen very much even though gas prices are down over 80% from their peak.

Plus, you missed out the eye-watering grid balancing costs for renewables that amounted to over £4bn last year, compared to £500m in 2011. Index linked CfDs for renewables and rising grid balancing costs drove the increase in electricity prices in the decade to 2021. Gas prices were pretty stable.

More here:

https://davidturver.substack.com/p/lies-damned-lies-wind-power-lobbyists

And here:

https://davidturver.substack.com/p/exposing-the-hidden-costs-of-renewables