Electric cars are the new solar: people will underestimate how quickly they will take off

Electric car sales are rising much more quickly than people – and industry analysts – expected.

Want to know how much solar power the world will be producing next year, or five years from now? Anyone that has followed solar’s evolution will know the golden rule: look at the International Energy Agency’s projection and assume it will be much more.

Year after year, the International Energy Agency (IEA) underestimated how quickly solar PV would grow.

You might have seen the infamous chart below (or a variation of it) comparing the IEA’s projections to reality. There are many versions and updates of this chart; this one is from the energy researcher, Auke Hoekstra.

It was reasonable that the IEA would get its projections wrong the first few times: that was to be expected for an emerging technology. What was odd was its failure to self-correct: despite being fiercely criticised for falling into the same trap, it did the same thing over and over.

It’s easy to criticise the IEA, but it’s not alone. Most of us underestimated how quickly solar would scale over the past decade.

Electric cars are becoming the new solar. They’re growing rapidly and will scale faster than most people expect, including the IEA.

Let’s take a look at the evidence.

Sales of electric cars are smashing all of the IEA’s previous projections

A few weeks ago the IEA published its 2023 Electric Vehicle Outlook report. It publishes this every year with the latest sales data, analysis, and projections for 2025 and 2030.

Global EV sales have grown rapidly in just a few years. In 2022, they were 14% of new car sales.1 In 2023, it expects this to be 18% – almost one-in-five – of new cars.

You might think these numbers sound small (after all, that would mean four-fifth of new cars are still gasoline). But here we’re focusing on the growth of these sales. In 2021, they were just 9%; in 2020, just 4%. EVs have gone from almost nothing to significant in only a few years.

The IEA expects EVs to be 23% of new car sales in 2025, and more than one-in-three (35%) by 2030.2

But what’s interesting is to look at how these numbers compare to the IEA’s previous projections. In the chart, I’ve plotted this.

In red we see the numbers from its most recent (2023) Outlook report. This shows the historic data, and what it expects in 2025 and 2030.

In the grey bars, I’ve shown the projections for 2025 and 2030 in its previous Outlook reports from 2019 to 2022 (going from left to right).

You can see that these projections were much lower. In fact, the jump from its 2022 to 2023 projection is enormous. Just last year it projected that in 2025, EVs would account for 15% of new car sales. It now thinks they will be around 23%.3

Last year, it thought EVs would be 21% by 2030; its updated figure is 35%.

This is such a dramatic change in EV’s prospects in the space of just one year.

[Download the underlying data from this chart here].We can also compare EV sales rates today to what previous outlooks were projecting years from now.

To make this clearer, in the chart below I’ve zoomed into the right half of the previous chart so we’re only looking at 2023 data and projections for 2025 and 2030.

Based on preliminary sales and policy data, the IEA expects that 18% of new cars sold this year will be electric. This is already higher than all of its previous projections for 2025, and it’s comparable to what was previously expected for 2030.

In other words: electric cars are years ahead of where many analysts expected them to be, as recently as last year.

China, the US and Europe have all upped their policies in the last year

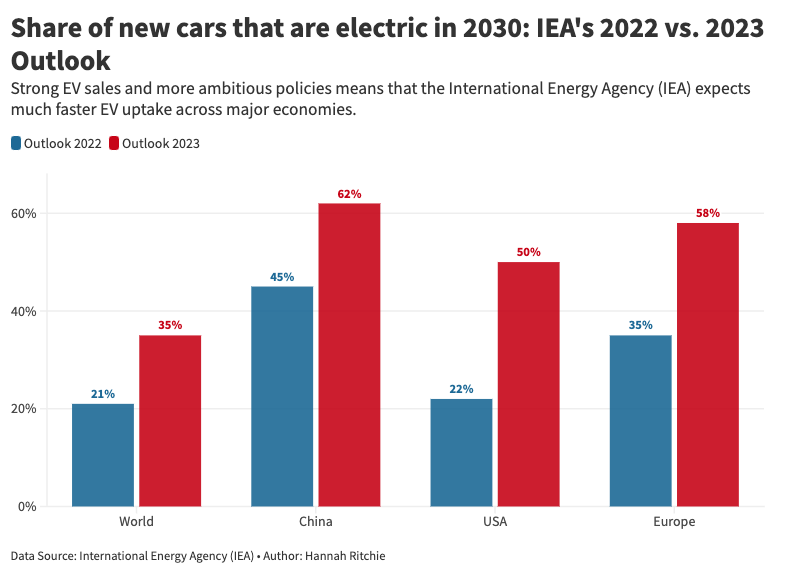

This jump in the IEA’s expectations from last year comes from a combination of stronger market sales and more supportive EV policies across major economies.

In the chart, we can see that the expectations for 2030 have increased a lot across China, the US, and Europe. These projections are largely based on the policies that countries have actually put in place (not the ambitions that they have announced).

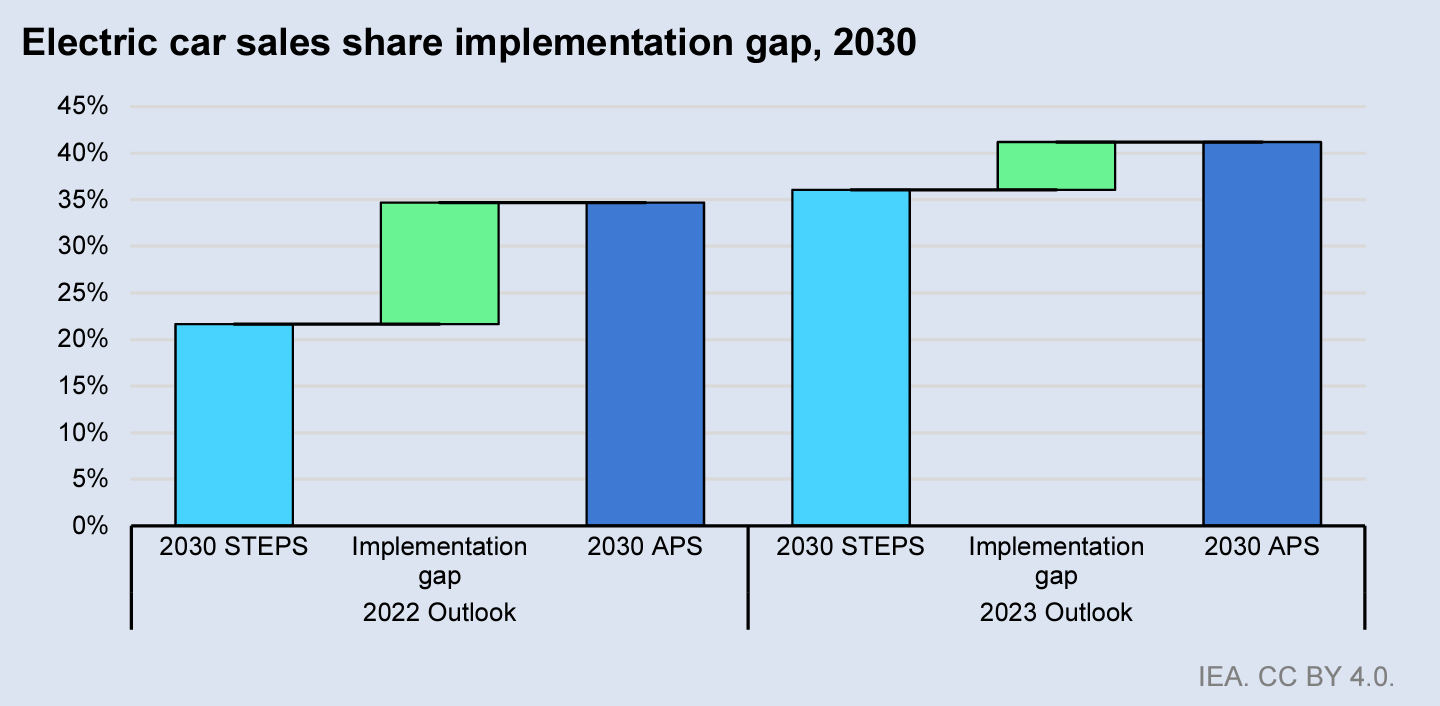

Over the last year, these countries have increased their ambitions but also closed the gap between their ambitions and the policies they need to make them a reality. The IEA shows this ‘closing gap’ in its 2023 Outlook report.

Here, ‘STEPS’ stands for the ‘Stated Policies Scenario’ that countries have put into practice. ‘APS’ stands for ‘Announced Policies Scenario’. This is what they’ve said they will do, even if they haven’t got the policies in place to make it happen.

You can see that in the 2023 Outlook, both STEPS and APS increased. But the gap between them also reduced. There were a couple of key policies that closed this gap, such as the US’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), and the European Union’s new CO2 standards for cars.

People often debate how important technology and economics are compared to politics. It’s obvious that both matter, and they often work together. Governments can only put ambitious policies in place if they have faith that the technologies will be available and cheap enough. They would not commit to large EV sales in 2030 if the technologies were poor and would make their populations bankrupt.

Game-changing technologies in a supportive policy environment can grow quickly. That’s exactly what we’re seeing with electric cars. And I expect that this is just the start: in the years ahead, EVs will continue to beat records and defy expectations.

This includes plug-in hybrids and battery-electric cars. Globally, more than 70% of new EV sales are battery-electric.

Note that the IEA does not give a precise figure in its 2023 Outlook for EV sales in 2025. It says it will be “over 20%”; from some extrapolation and basic reading of trends, I expect this to be 22% - 24% based on its 2030 projection. A figure of less than 22% would suggest that the IEA expects growth to be slow between 2023 and 2025.

See footnote two.

Great piece Hannah. I’ve found the IEA’s forecasting (and particularly their inability to learn from their mistakes) particularly amusing over the years. We humans really struggle with non-linearity don’t we?

All we need is more reliable and affordable electricity production and we will be on our way. The main barrier to that is that we have no cheap scalable way of dealing with intermittency that does not involve fossil fuels. This is where nuclear is essential, as only with nuclear do we know we can have zero emission reliable and cheap electricity, which is obviously essential for electrifying transport and heating.

Without nuclear we will have to pray for revolutions in storage and/or carbon capture.