How big is the generational divide on climate change?

The generational divide on belief and concern about climate change is small; there are slightly bigger gaps in what to do about it.

Most people underestimate how many people “believe” in human-driven climate change and care about tackling it. This is true in almost every country. I’ve written about this before.

This matters because our perceptions about levels of support for climate action can affect our willingness to make changes as individuals, but also influence the decisions of businesses and policymakers. After all, politicians need to speak to what the public cares about. Companies do, too.

But this misperception also applies to specific demographics. There is a notion that young people care and are terrified about climate change, while older people care much less (if at all). And I think this mischaracterisation goes both ways: young people are framed as unreasonable and self-righteous, while older people are ignorant and selfish.

When I was much younger I definitely went through an angry “older generations have screwed us over, and few of them care about it” period. That’s not my perspective anymore, but it’s a feeling that I think many people still hold. Regardless of what you think about the first half of that statement, data suggests that the second half is incorrect. The generational divide in belief and concern about climate change does exist, but it’s much smaller than people imagine. Almost too small to matter.

There are, however, some differences in what older and younger generations think we should do about it.

Two disclaimers before I start. First, this post contains generalisations: I’m using average population-wide data, and matching that with personal reflections. It doesn’t apply to everyone.

Second, I’ll be looking at survey data, which is always notoriously messy. The framing of questions can affect the answer, and people are fickle, so what they say on a Tuesday isn’t always what they’d say if you asked them on a Friday. I’ll do my best to provide some overarching messages that seem to be fairly consistent, but the conclusions are not always perfect.

The generational differences in “belief” about climate change are smaller than many people think

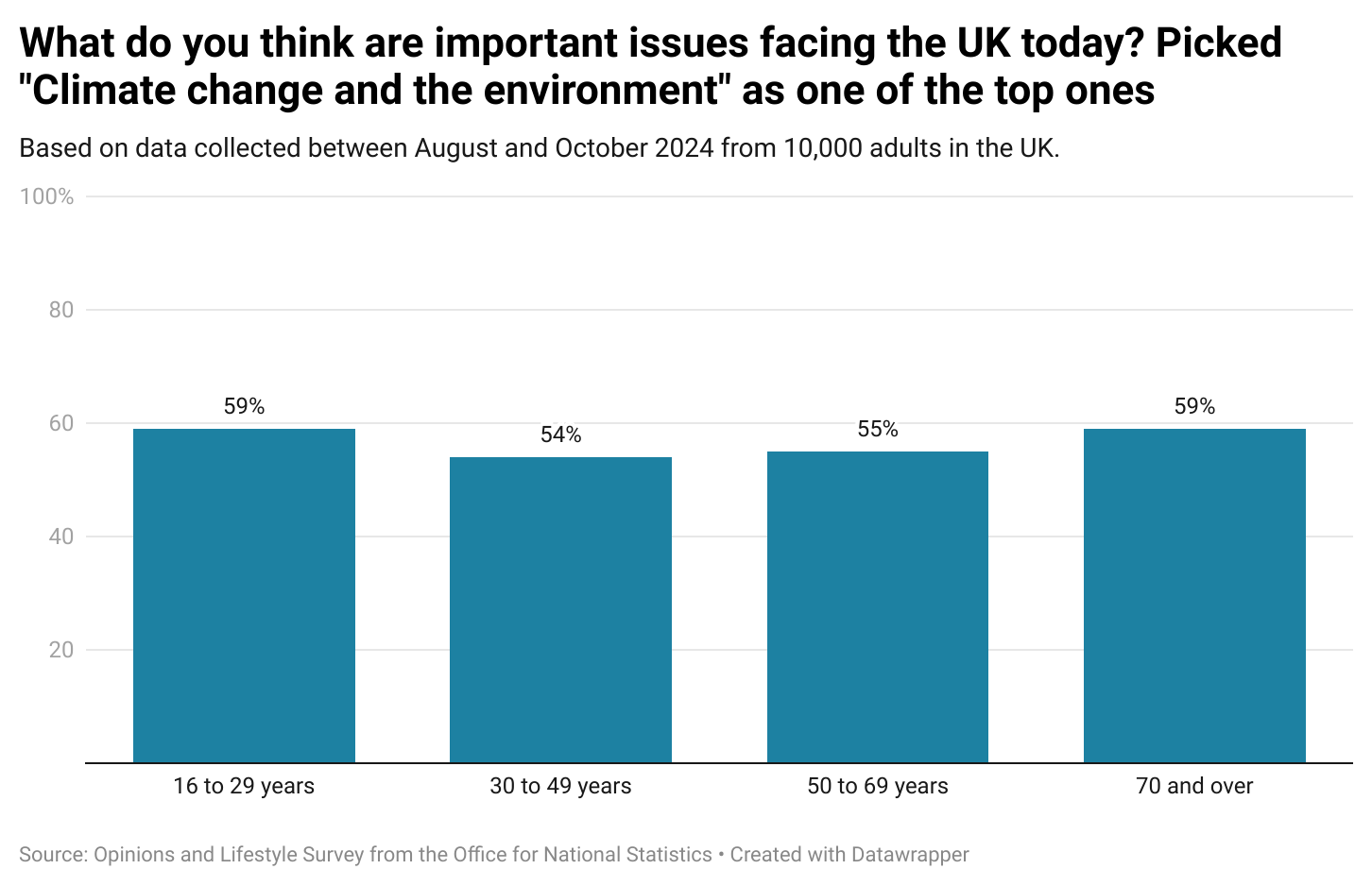

The UK government runs pretty extensive surveys on the public’s attitudes to climate change. In the chart below, you can see the share of different age groups that selected “climate change and the environment” as one of the top issues facing the country. This was based on data from 10,000 adults in 2024.

Note this has a higher bar than simply thinking climate change “exists” or is a problem. It’s the share that thinks it’s among the most important issues.

There is little difference between generations, and the oldest think it’s just as important as the youngest.

This scientific paper — published in Nature Communications — found similar results based on UK data across multiple years.1 There was very little difference in beliefs about climate change, or the cause between generations. “Baby Boomers” were just as likely to say that climate change was happening, humans are causing it, and it’s an urgent problem as Millennials or Gen Zers.

Interestingly, older generations were more likely to say that they (or we) were already feeling the impacts. This would make sense: they have over 60 years’ worth of “real-life” data on how weather, temperature and seasons have changed. Often it’s the more subtle changes that people notice: planting or blossom timings, or the frequency of winter snow. Older generations have been there and lived through it.

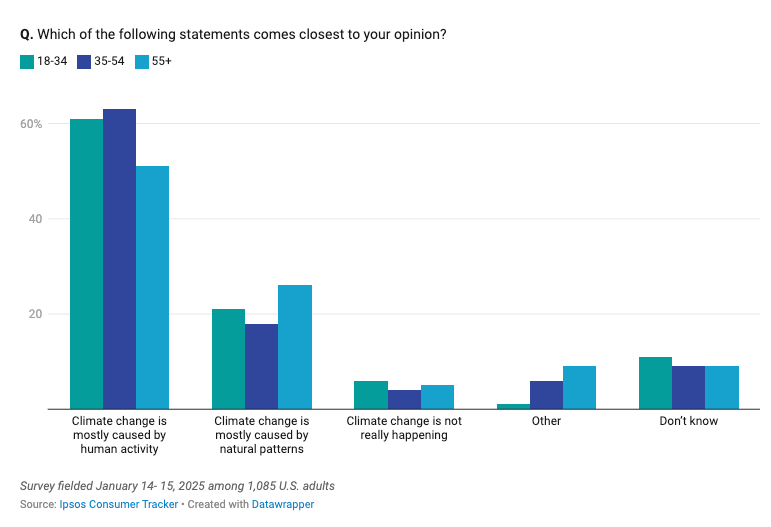

The overall polarisation on climate change in the UK is — by global standards — relatively small. In the US, things are a bit more contentious. Let’s look at some data from there.

In the chart below, you can see early 2025 survey results from Ipsos. There is more division on whether humans or natural patterns are causing recent climate change; older generations are a bit more likely to say the latter. But the gaps are still not huge. The majority of older people still think climate change is a human-caused problem.

Interestingly, there is no generational gap among Democrats. It’s among Republicans where younger generations are more likely to diagnose and recognise climate change as a human-driven problem.

Australia and New Zealand are two other countries where generational gaps exist. However, research from the latter suggests that the change or increase in climate change beliefs has increased at the same rate across the generations; the reason for the generational gap is simply that older people started from a slightly lower base.2

Older generations report lower emotional responses to climate change

Before we get on to actions to tackle climate change, the earlier study from the UK did identify generational gaps in emotional response.

The gaps on “worry” were not huge. But, younger people were more likely to say that they felt fear, guilt and outrage. I don’t think anyone would be particularly surprised by this result. Nor do I think that this is an irrational emotive response.

Younger generations will have to contend with the worst consequences of climate change for most of their lives. Older generations, to be blunt, won’t. It reflects the poster that you often see young people holding at at youth protests: “You’ll die of old age, I’ll die of climate change”.

Maybe this difference is why many people think there is a huge generational gap. Often, survey questions ask whether someone is fearful, worried, angry, anxious, [insert emotion here] about climate change. Older people might be more likely to say no. But that does not necessarily mean they don’t think it exists, or isn’t a problem.

Older people are more likely to focus on individual lifestyle changes; young people on systemic change

Beliefs about what to do have wider generational gaps.

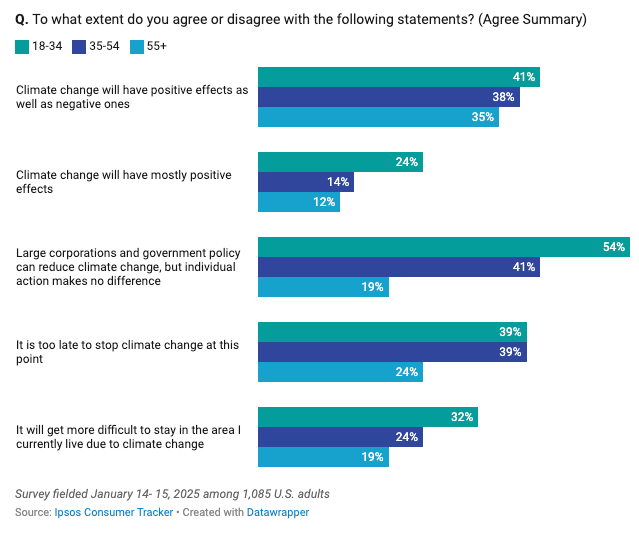

Back to the results from the US Ipsos study again. The focus here is not on the first two questions in the chart below (although the results are interesting; younger people seem to be more likely to report some positive effects of climate), so you can skip over those.3

When asked about whether “individual action makes no difference” more than half of 18 to 34-year-olds said yes. In other words, it’s large corporations and governments that need to fix this, not the public. The share among those over 55 years old was just 19%.

I’ve written before about why I think the systemic change versus individual change question is a false dichotomy. No, individual behaviour change won’t solve this, but we can’t all stick with our petrol cars and gas boilers and expect the problem to disappear. Public acceptance of change needs to be combined with higher-level changes from governments, industry and business.

Before seeing these results, I would have guessed that older generations are more likely to focus on individual responsibility, and younger generations on systemic change. I often see it in the topics that people bring up when I do interviews or events. I am generalising here, but older generations will often bring up population growth; to tackle this problem, individuals need to have fewer kids (if any). Or the focus is on energy conservation: before thinking about getting an electric heat pump to cut emissions, get a couple of extra jumpers on and turn the thermostat down.

Younger people are more likely to bring up economic change; to tackle the problem, we need to find a system-wide alternative to capitalism.

The next question in the chart below also shows interesting results. A staggering 39% of young people said that it was too late to stop climate change at this point. Again, survey questions are often hard to interpret. Do people assume this means it’s impossible to stop climate change from progressing at all at this point? That I would also agree with: emissions are not going to zero tomorrow, so climate change will get worse for some time. Or do people assume that there’s nothing we can do to solve or stop climate change in the long-term? That is a hopelessness I don’t share, and frequently push back on.

Regardless, a much smaller share of the oldest generation thought that the battle against climate change is lost and it’s “too late”.

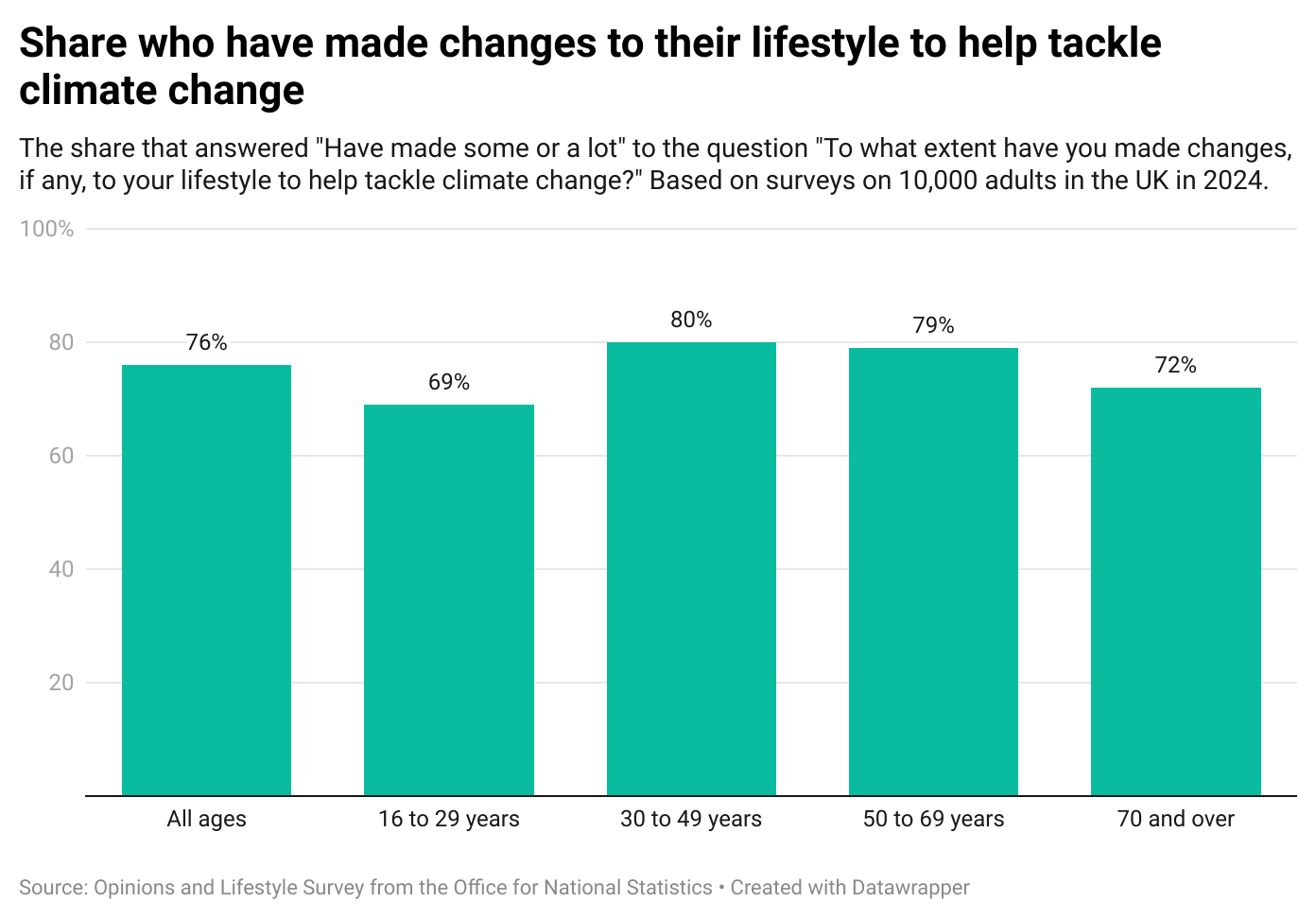

What about people actually making lifestyle changes? In the large UK survey there doesn’t appear to be huge differences across generations. In fact, the share was lowest among the youngest and oldest age brackets.

Again, a word of caution here: people will have very different thresholds for what they consider to be lifestyle changes. Some will think it’s putting solar panels on the roof and ditching the petrol car. Others will think this is recycling or replacing inefficient lightbulbs. So we’re not necessarily measuring like-for-like, or measuring the actual impact of these changes in terms of emissions.

It’s worth noting that some lifestyle changes are out of reach for many younger people, especially those who don’t own a car or a home. They can’t install solar panels or an electric heat pump, and maybe travel in a fairly low-carbon way anyway. But with this broad definition of “lifestyle changes”, I don’t expect the overall results to be affected much by this: changes in diet, purchasing decisions, travel, joining an action group etc. all count.

The 24% of adults who hadn’t made changes to help tackle climate change were asked why. The most common reason — at 42% — what that they didn't think their changes would have any effect on climate change. This was followed by 37% who said that large-scale polluters should change first. Alas, this is a common narrative, even among prominent climate advocates and communicators, but I think it’s an unhelpful one.

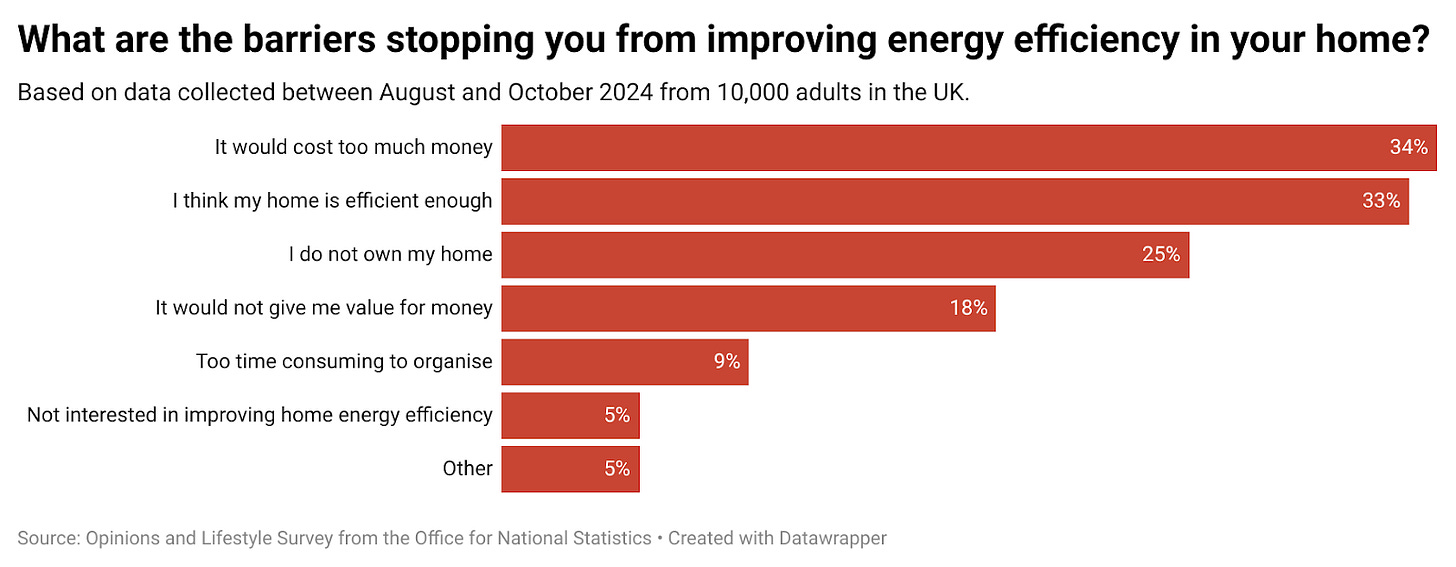

When asked about specific changes — particularly larger ones that make a bigger difference — cost was often top of the list. Here are the results for improving energy efficiency at home. Again, these results will be skewed towards older generations because younger ones are less likely to own a home that they can insulate.

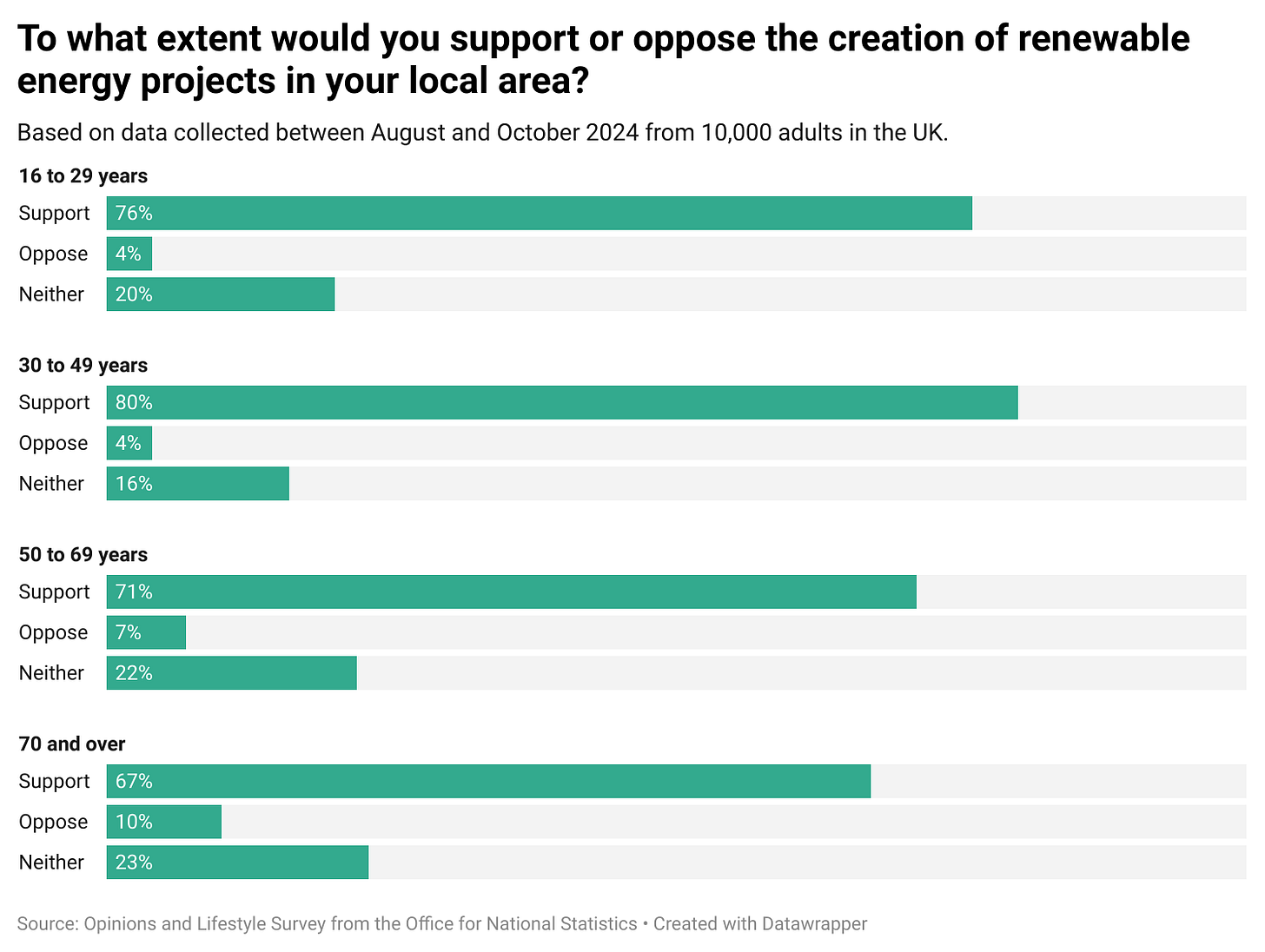

One of the final questions in the UK survey was about support for local renewable energy projects. The first thing to notice is that support is high across the generations. Again, a fair warning: saying you’re happy to have a wind farm in your area in the survey might not always align with your response when they start putting the turbine up.

The oldest generation was a bit more likely to oppose a local project: 10% versus 4% in the youngest generation. This doesn’t surprise me. Older generations will often have lived in their home and local area for a long time. They probably feel more strongly about protecting the way the landscape has looked for most of their lives.

Data from another UK government survey found that under-35s were less likely to be opposed to a wind farm in the local area. Home ownership might also play a role here: those who own their house are probably worried that wind farms will reduce their value.

People of all ages care about climate change

My point is not that generational gaps are completely absent in the climate change debate. It’s just that they’re often smaller than many people imagine. Small enough for them not to get in the way of us moving forward.

This lack of generational gap became clear to me on a personal level when I published my book Not the End of the World last year. In it, I say that I was writing this book for my former, younger self. You might expect, then, that it would resonate most strongly with young people. And it did: I’ve heard from many.

But I’ve received just as many emails (or often hand-written letters), and had just as many talk attendees from older generations. They are concerned about climate change — often citing their love for their children and grandchildren as their motivation — and want to make a difference.

Poortinga, W., Demski, C., & Steentjes, K. (2023). Generational differences in climate-related beliefs, risk perceptions and emotions in the UK. Communications Earth & Environment, 4(1), 229.

Milfont, T. L., Zubielevitch, E., Milojev, P., & Sibley, C. G. (2021). Ten-year panel data confirm generation gap but climate beliefs increase at similar rates across ages. Nature communications, 12(1), 4038.

What's interesting is that the results are not necessarily internally consistent.

Younger generations were more likely to say that climate change can have positive effects, but also more likely to say that it will get more difficult to live in the area that they live.

As a (near) 70 year old, I too enjoyed your thought provoking book. I have children and grandchildren, and their future welfare is at the forefront of my mind in looking to do something about climate change. I also agree that individual actions are just as important as actions taken by governments and corporations. We are all in this together! So I believe nearly everyone can do something - from lightbulbs to insulation to heat pumps and solar panels. Even adjusting settings on a gas boiler can reduce gas consumption, cost nothing and save money!

Many thanks for your well informed and data driven blog.

What might be helpful to remember — for people of all ages — is that climate change isn’t entirely new or unprecedented. It’s another example of a pattern we’ve seen before:

• Science or technology brings progress — but also unintended harm

• Scientists detect the damage

• Powerful interests deny or delay

• Eventually, the truth prevails and society acts

We’ve seen it with lead in gasoline, tobacco, CFCs and the ozone layer, DDT and more. In each case, science helped solve a problem it helped create — despite denial and delay.

One encouraging constant? Younger generations tend to internalize scientific realities more quickly. They’ve often been the first to push for action, and their instincts have usually been right. The real question now is whether we let delay win again, or finally break the pattern.