The world likes big cars, the data don’t lie 🎶

As promised, here is a look at how cars compare across the world in terms of size, fuel economy, CO₂ emissions, and why this matters.

When I think about cars in the United States, the image of big SUVs and pick-up trucks come to mind.

This is not just a stereotype from the movies. Look at the data, and we find that cars in the US are getting bigger and heavier. More than half of new cars sold are SUVs – most of them big SUVs. I wrote about how cars – their size, efficiency and fuel economy – were changing in the US in a previous post.

The US might still be an outlier, but the rest of the world is following its lead. As we’ll see, cars across the world are getting heavier, and SUVs are taking an increasing share of the market.

In this post I look at how cars compare across the world, and why this matters.

Americans, Canadians, and Aussies love their big cars

How does the size of cars vary across the world?

In the chart, we see the average weight of passenger cars across a range of countries in 2021. This data comes from the International Energy Agency (IEA).

At the top we see three outliers: the US, Canada, and Australia have the heaviest cars by far. These weigh in at just under 1800 kilograms (or 1.8 metric tonnes). I can half-understand why Canadians might opt for a bigger car: probably pretty useful in brutal winters and deep snow. Why the Aussies need massive cars is a bit beyond me.

In the mid-range, we have a range of countries – spanning different regions, but mostly of a high or upper-middle income.

The smallest and lightest cars – as you might expect – tend to be in countries of lower incomes: Indonesia, Malaysia or India, for example. But there are a few surprises. Cars in France and Italy are pretty small. And most surprising are cars in Japan – which are some of the lightest in the world, despite its levels of wealth. The average car in Japan is just two-thirds of the weight of cars in the US.

Japanese cars are not small because people can’t afford bigger ones.1 They’re small because of policy incentives and cultural norms. Japan has a special category of compact car – called the Kei car – that is incredibly popular. For years, the Japanese Government has incentivised Kei cars by offering tax breaks and insurance incentives. With a lower cost, and higher efficiency, these cars are well-suited to dwellers in Tokyo and other dense cities.

Cars are getting heavier across the world

Most of the world has being following in the Americans’ footsteps.

Cars are not just getting heavier in the US, Canada and Australia. They’re getting bigger almost everywhere.

In the chart we see the change in the weight of the average car sold in the United States and European countries since the millennium.2 Between 2001 and 2020, the EU average increased by around 13%.

In some countries, the change was even larger. Cars in Austria are one-third heavier. In the UK, Spain and Finland they’re 25% heavier. And in Sweden, weights have increased by 20%.

The only country where cars got slightly lighter was Portugal.

Here I’m focusing on data from Europe because it has long-term, consistent trends to compare. But by looking at shorter time-series, we see that cars outside of Europe are getting heavier too. Cars in China are 20% heavier than in 2005. In Argentina and India, they’re about 10% heavier.

There are two big drivers of heavier cars.

One is that the medium car (often called a ‘sedan’ or a ‘wagon’) is getting bigger. As I showed in my post on cars in the US, the average ‘sedan’ in the US is 15% heavier than it was a few decades ago.

The second is that more and more people are moving towards SUVs (“sport utility vehicles”), which are usually heavier than a standard car.

This move to SUVs is almost-universal across the world. Almost half of the world’s new car and van sales are SUVs. And as we see in the chart below, this is not limited to only a few countries. In Canada and the US, well over half are SUVs. In China, it’s over 40%. And in India, it’s almost one-in-three.

Again, one of the few exceptions is Japan, where SUV sales are rising slowly but are far behind the rest of the world.

Why does the size of cars matter?

Why does this even matter? Why do we care about the size or weight of vehicles?

There are a number of reasons why.

1. Fuel and carbon economy: The bigger the car, the less fuel-efficient it is

Perhaps the most obvious impact of bigger cars is fuel economy and their climate impact. In general, the heavier the car, the more fuel it needs (and, therefore, the more CO2 it emits).

In the chart I’ve plotted average CO2 economy – which is measured as the amount of CO2 emitted per kilometre – versus the average weight of cars by country.

We see a positive – albeit not perfect – relationship. In general, the heavier the car, the more fuel it needs (and the more CO2 it emits). Weight is not the only thing that matters. Design and technology make a big difference too. We can see that CO2 economy tends to be poor in lower-middle income countries such as Indonesia and Malaysia, despite the average car being relatively light. And CO2 economy in Europe tends to be good, despite these cars being heavier.

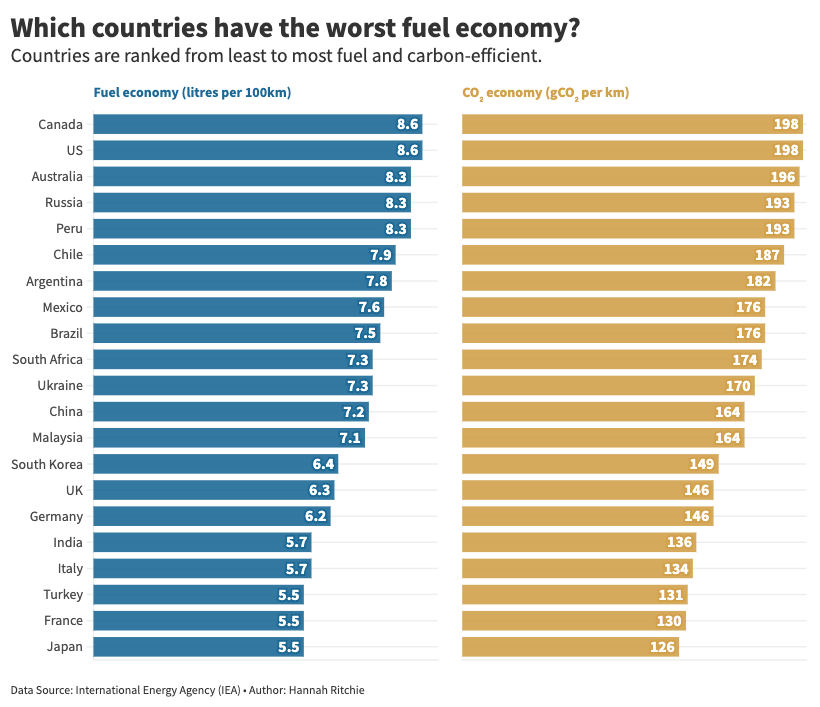

Let’s then take a better look at how fuel economy and CO2 economy vary across the world. In the chart, we see countries ranked from least to most fuel and carbon-efficient.

Canada has the worst fuel economy. To drive one kilometre, the French and Japanese use just two-thirds of the fuel as the Canadians. That also gives them the worst CO2 economy. The Americans and Australians – due to their big cars – are not far behind.

It’s important to clarify that fuel economy is not necessarily getting worse over time, as cars get bigger. In fact, in most countries, the general trend has been the opposite. Car technologies have made great strides over the last 50 years, such that the average car today is much more efficient than it was back then. Even if it’s bigger.

The average car in the US, for example, gets twice as many miles per gallon as it did in 1975. Fuel economy has doubled. And that’s despite the dramatic rise of SUVs.

The point, then, is not that all of the gains in fuel economy have been offset by bigger cars. That’s not true. But some of the efficiency gains have. Fuel economy has improved, but it could have improved by much more.

A world with smaller cars would use much less oil and emit much less CO2.

2. Air pollution: Bigger cars tend to be worse for local pollution

Burning more fuel doesn’t only matter for the climate. It also matters for local air pollution. Road transport is a major source of air pollution – particularly in cities. How polluting a vehicle is depends on a range of factors.

One of them is how much fuel you’re burning: burn more petrol or diesel, and you generate more tailpipe emissions.

Heavier cars can also increase pollution from tyre wear and the suspension of particles from the road surface itself.

All else being equal, smaller cars are better for local pollution and human health.

3. City design: Our cities were not built for SUVs and monster trucks

Many of our cities have been designed to handle cars from decades ago. Our parking spaces, driveways and streets were not built for the cars we have today.

It might seem like a feeble point, but this matters. When our cars get big, everything needs to get bigger to accommodate. Bigger driveways, wider streets, more sprawling parking lots.

4. Safety: You’re safer in a big car, but put others at higher risk

There is an unfortunate ‘catch-22’ when it comes to car size and the risk of dying in an accident. There is now a large bank of research on how car size and weight affect safety on the roads.

You’re safer as the driver, or passenger, of a big car. In a crash, you’re better protected. The problem is that you put others around you at greater risk. Hit a smaller car, and you’re hitting them with more force. The bigger your car, the more likely they are to die in that crash.

You put pedestrians at a higher risk too. There are a couple of reasons for this. First, a heavier car hits them with more force. Second (and I apologise for the visuals of this), where you strike them is different in a taller car. In smaller cars, you’re more likely to strike their legs and they’d been thrown onto the hood of the vehicle. In larger cars, you’re more likely to hit them in the torso, or even the head. This not only risks damage to their internal organs and brain injury, but it can also throw them under the vehicle.

There’s lots of research to back this up. Pedestrians hit by SUVs, pick-ups, or minivans were much more likely to die or suffer brain injury versus being hit by a conventional car.3 Studies have estimated that mortality rates for pedestrians are at least 50% higher, and up to 2 to 3 times higher, in large vehicles.4

Look at the change in road deaths in the US from 2000 to 2018, and we see a 32% decline in motorist deaths, but a 20% rise in pedestrian deaths.

In safety terms, it has become a bit of a reinforcing loop. If all of the cars around you are getting bigger, the best way to protect yourself is to get a bigger car too.

5. Electric cars: The EV market will become an arms-race for big cars

Finally, the growing market for big cars matters as the world transitions to EVs.

Electric cars – because of their battery – would be slightly heavier than an identical gasoline car. What we want to avoid is a continued arm’s race towards bigger and bigger EVs. We already see this in the market. There are now many large, luxury EVs on sale.

There are far fewer small, budget models. This can mean the entry point for an EV is out-of-reach for many people.

I can understand why car manufacturers are targeting SUV and large-car markets. That’s where the customers are.

But to electrify entire fleets of cars we need models across the full price and size spectrum. And we need a lot of smaller, affordable ones. The more obsessed we become with large gasoline cars, the less likely this becomes.

Although one of the initial drivers for Japan to generate a domestic Kei car market was to provide affordable transport following World War II.

Many Japanese citizens couldn't afford large cars, so this was one step up from the motorcycle.

US data comes from the US Environment Protection Agency. European data comes from the European Vehicle Market Statistics.

A quick note on the metrics here.

You might notice that the final weights of cars here are larger than they were in the previous chart.

One reason is that the data used in this chart – which comes from the US EPA and European Vehicle Market Statistics – adds estimated weights for passengers and cargo. This is sometimes called the 'Mass in running order'.

In the previous chart, we looked at 'Kerb weight' which does not include this.

It would be nice if these metrics matched, but these differences don't affect our results. They're internally consistent. The cross-country comparisons above use the same units. And in this chart, it's the change over time that matters. For that, all we need is the same metric in 2001 and 2020 (which we have).

Simms, C.K. and Wood, D.P (2006). Pedestrian risk from cars and sport utility vehicles a comparative analytical study. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, PartD: Journal of Automobile Engineering, 220(8):1085–1100.

Lefler, D.E. and Gabler, H.C. (2004). The fatality and injury risk of light truck impacts with pedestrians in the United States. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 36(2):295–304.

Desapriya, E., Subzwari, S., Sasges, D., Basic, A., Alidina, A., Turcotte, K.,and Pike, I.(2010). Do light truck vehicles (LTV) impose greater risk of pedestrian injury than passenger cars? A meta analysis and systematic review. Traffic Injury Prevention, 11(1):48–56.

I think we should accept that SUVs are here to stay. There are some sacrifices that people will not make for the environment. People will not turn off their air conditioning in the summer, and they will not give up their SUVs.

We should solve the problems of carbon emissions and air pollution by moving to electric vehicles and green energy.

There is perhaps one additional factor and that is the size of the individuals in the vehicle. We yanks are larger and physically need more volume for equivalent comfort. Als you note, the stuff around making roads and parking larger is definitely a requirement. I have a Dodge Ram 1500 and it’s a beast to park.