Do more people die from heat or cold? How will this change in the future?

An overview of temperature-related deaths, and how this might change with climate change.

Navigating debates on heat and cold deaths is a bit of a minefield. Some headlines report there will be an unprecedented wave of heat deaths as the planet warms. Other commentators claim that deaths will go down because far more people die from cold than heat. It’s hard to get a grasp on what’s going on.

At Our World in Data, I recently wrote a four-part series on heat and mortality, and what we can do about it.

But, since this is such a hot topic, I thought it was worth giving a shorter version of the key points here. If you want to dig deeper, I’d recommend going to read my original articles (I’ve linked them all at the end of this post).

Without further ado, here’s what I think you should know about heat and mortality to understand the problem better.

1. Researchers often rely on temperature-mortality curves to estimate cold and heat deaths

Before we talk numbers, we first need to understand how researchers estimate how many people die from heat or cold.

One method is using established temperature-mortality curves. They look something like the one below. 1 The relative mortality risk is on the y-axis, and temperature is on the x-axis.

As you can see, there is a “minimum point”: this is the ideal temperature where mortality risks are lowest. When temperatures are colder or warmer than this, mortality risk increases for a variety of reasons: increased risk of flu and infectious diseases; cardiovascular disease, stroke, kidney disease etc.

The curves tend to follow a similar pattern where the increased risk of mortality just below or above the “optimal temperature” is relatively low, but rises steeply towards much more extreme cold or heat.

Most of us spend most of our time in the “moderately cold” or “moderately warm” conditions. Remember this, because it’s important for later.

These temperature-mortality curves vary across the world. In the chart, I’ve shown some of these curves for different cities. These are the real curves that researchers use in studies on how many people die from extreme heat; they’re not schematics.2

The “optimal temperature” and shape of these curves vary for a bunch of reasons. People acclimatise to local conditions, so they are better at dealing with heat after living in a warm country for a while. Access to cooling or heating also plays a role: most people in Austin, Texas have air conditioning, so they’re at much lower risk of dying in extreme heat than someone in London or Paris, where air conditioning is almost non-existent.

This also means that the shape of these curves could change over time. People might become more acclimatised to warmer temperatures. And they will get access to cooling or heating that lowers the risk at the extremes. How much will change is still a big question mark that makes estimates of future heat deaths uncertain.

2. Today, far more people die from cold than heat (but most die from “moderate cold”)

Far more people die from “cold” than from heat. This is a consistent finding across the scientific literature. What varies is the magnitude of this difference: some studies estimate that cold deaths outnumber heat ones by 9-to-1.3 Other studies have different ratios, but the direction of the result is the same.4

Cold deaths outnumber heat deaths everywhere in the world; not just in colder climates.

But it’s really “moderately cold” deaths that explain most of this.

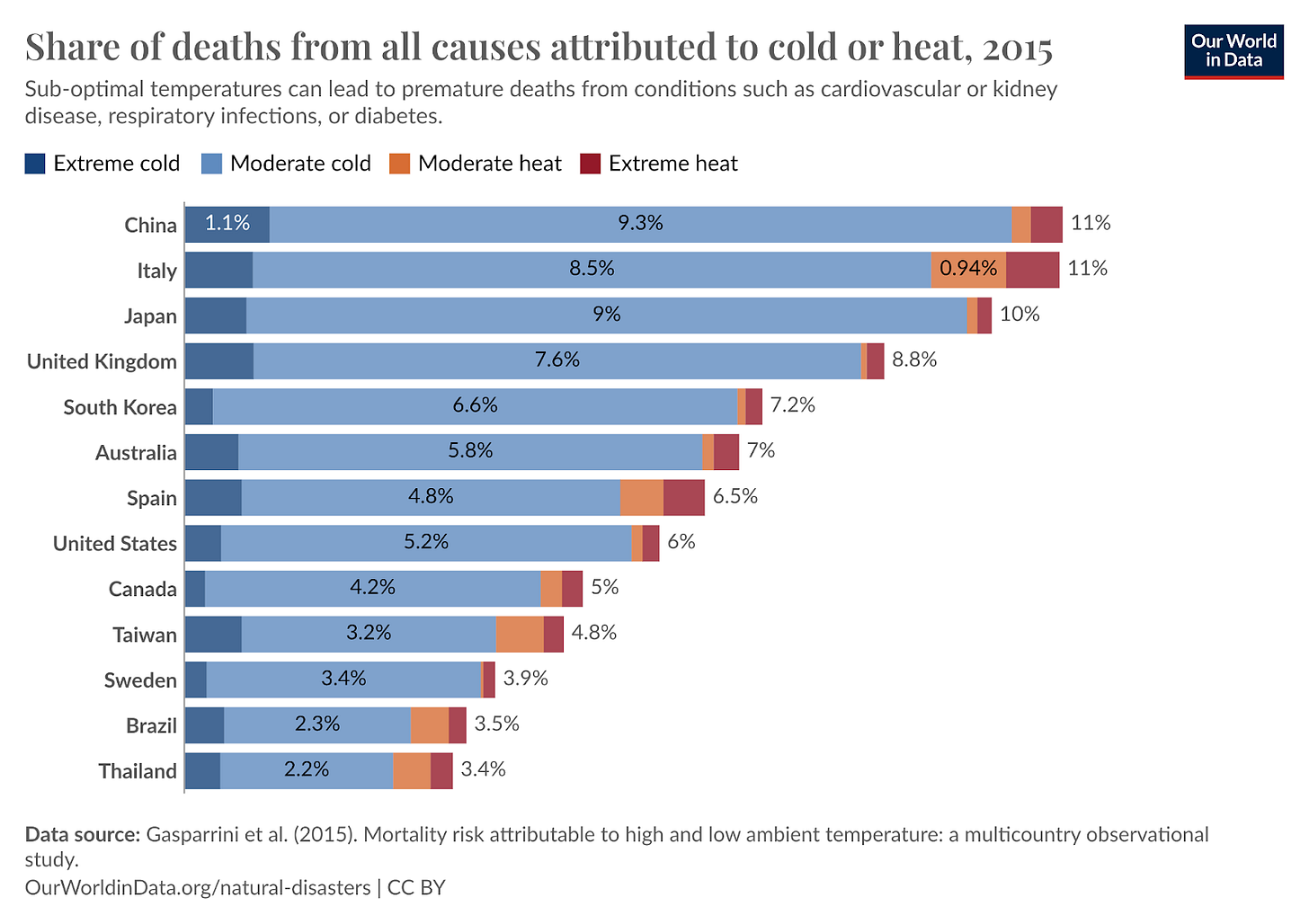

In the chart below we see the breakdown of premature deaths attributed to extreme cold, moderate cold, moderate heat, and extreme heat.5

Most people are dying prematurely from “moderate cold”. Again, this is not because the risk of mortality is high in this zone; it’s because we spend most of the year in those temperatures. You might have noticed in the previous section that the “optimum temperature” is higher than we might expect. For London, it’s around 18°C. That means 16°C would be considered “moderately cold” but that’s what many Brits would consider to be an early Summer’s Day. “Moderately cold” is not what most of us would consider to be cold at all.

When we think about “cold” or “heat” deaths we’re usually thinking about someone dying from hypothermia in sub-zero temperatures; or dying of heat stroke in extreme 45°C heat. But this is a minority of temperature-related deaths.

3. Without adaptation, temperature-related death rates will rise in poorer countries but fall in richer ones

The world is going to get warmer. What’s going to happen to temperature-related deaths? Are they going to rise from increased risks of extreme heat, or fall from lower risks of extreme cold?

Both.

It’s worth noting that future death rates from cold or heat are much harder to estimate than historical or current ones. Again, this is because we don’t know the extent to which individuals and communities can acclimatise or adapt.

But in the map below you can see estimates for the change in death rates from temperature in 2050 under the climate scenario RCP4.5.6 This is a pretty realistic scenario based on where we’re headed right now, but the hope is that we can bend it downwards with accelerated efforts to reduce our emissions. RCP4.5 will have us at around 2°C by 2050.

The countries in blue will see a fall in temperature-related death rates. Death rates from extreme heat will probably still rise, but the fall from fewer cold deaths will be faster. That means total temperature-related deaths will go down. You can see that this is mostly richer countries at higher latitudes — across Europe, Canada and the United States.

Those in red will see an increase. The rise in heat risks will outpace the reduction in cold risks. This is most of Northern and Central Africa, South Asia, Australia and parts of South America.

Here’s another way to look at this. It measures the change in temperature-related deaths from 2030 through to 2090 under the same RCP4.5 scenario. Deaths in richer countries like the UK, France, and the United States are going down. Deaths in India, Nigeria, and countries in the Middle East are going up.

This underlines the brutal reality of climate change. Those countries that have historically emitted the most CO2 — and contributed most to the problem — might actually “benefit” from higher temperatures.7 Those who have contributed almost nothing are the ones who are going to pay the highest price.

You can see this quite clearly in this scatterplot of CO2 emissions per person versus the change in heat deaths. Deaths are going to go up among countries with very low carbon footprints. They’re going down for those with higher emissions.

4. We need to stop treating air conditioning as a luxury

Air conditioning is going to be a life-saving technology for many, especially as the world gets warmer. But even taking climate change aside, lots of people in the world would benefit from air conditioning. They’d be able to sleep better in stifling heat; children would perform better at school; economic productivity would go up.

The main thing stopping them from getting air conditioning is cost. They can’t afford it.

More broadly, we need to rethink how we view and talk about air conditioning. Except for a few countries like the United States, Japan and South Korea, it’s still seen as a luxury. Adoption rates in Europe — where many people could afford it — are incredibly low.

It’s interesting to consider how people talk about cooling compared to heating. The world uses a lot more energy for heating than for cooling. This also means the energy-related emissions from heating are about four times higher than for cooling.8

In Europe, if someone can’t afford heating then they’re defined as being in “fuel poverty”. There is (quite rightly) outrage about the fact that fuel poverty still exists. What’s strange, though, is that cooling is almost treated in the opposite direction: having an air conditioner is seen as a luxury or overconsumption. But it also saves lives, and would have a huge impact on many people’s level of wellbeing and productivity.

Both heating and cooling come at an energy and climate cost, so I know this might be an unpopular take. I’ve written about this in detail here if you want a run-down on the numbers. I’m not advocating for everyone blasting their aircon or heating 24/7. We need to build insulated homes; have efficient heating or air conditioning systems; and be reasonable about what temperature to set the thermostat. Yes, put on a jumper in winter, and take it off in the summer.

But we probably underestimate how important temperature is to overall well-being and need to get away from the mentality that we should just grit our teeth and suffer through. Note that I’m bad at taking this advice myself ( mostly for heating, not cooling, since I live in Scotland).

The stigma around air conditioning is, ultimately, going to cost lives if we don’t rethink the benefits of it.

5. There are other things we can do to protect people from heat

Of course, air conditioning is not the only way to protect people from heat. There are plenty of reasons why we shouldn’t rely on it alone.

Some people won’t be able to afford it, even a few decades from now. We want to be able to protect people if the grid goes down during a heatwave. Some people need to work outdoors and can’t stay inside their air-conditioned homes all day. We want to save energy (and the climate impacts that come from it) where we can.

There’s a lot that we can do from the perspective of city design and architecture to keep our homes cooler. I cover these techniques in much more detail in one of my articles.

Keeping city streets narrow means they’re only exposed to the blaring sun for a tiny fraction of the day. Having trees and vegetation provides shade and also increases evapotranspiration. Painting roofs white, or having “green roofs” can help. And thinking about the materials we use to build houses can make a big difference.

All of these techniques will keep our cities and communities cooler, while saving energy from air conditioning at the same time.

When combined with effective public health programmes that provide support, guidance and treatment on extreme heat days, we can do a lot to protect people from heat even in a warming climate. It might be inevitable that heat-related deaths in many countries go up this century but how much is up to us.

Final note

If you’re looking for a challenge to work on over the next decade, innovating on better air conditioning technologies that are cheaper and more efficient, would be very high-impact. Billions of people who would benefit hugely from air conditioning currently can’t afford it. We want them to get it without breaking our electricity grids, and hampering our climate goals.

This is also true for heating. A lot of people still die from cold, and we shouldn’t forget about protecting them too.

Read more

This is a shortened and simplified summary of a series that I’ve written for Our World in Data on heat and mortality. I couldn’t cover all of the intricacies and questions you might have.

If want to dig deeper, here they are:

How many people die from extreme temperatures, and how this could change in the future: Part one

How many people die from extreme temperatures, and how this could change in the future: Part two

Air conditioning causes around 3% of greenhouse gas emissions. How will this change in the future?

Note that this is just one method they use. They can use others, like excess mortality, which tells us how many more people died in a given year (such as one with a heatwave or particularly cold conditions). than we’d expect in a “normal” year.

Chen, K., De Schrijver, E., Sivaraj, S., Sera, F., Scovronick, N., Jiang, L., ... & Vicedo-Cabrera, A. M. (2024). Impact of population aging on future temperature-related mortality at different global warming levels. Nature Communications.

Zhao et al. (2021). Global, regional, and national burden of mortality associated with non-optimal ambient temperatures from 2000 to 2019: a three-stage modelling study.

A study across 854 cities in Europe found that cold-related deaths were around ten times higher than heat-related ones.

A detailed study across England and Wales found that cold-related deaths were two orders of magnitude higher. The same is true for China. And the United States.

Masselot, P., Mistry, M., Vanoli, J., Schneider, R., Iungman, T., Garcia-Leon, D., ... & Aunan, K. (2023). Excess mortality attributed to heat and cold: a health impact assessment study in 854 cities in Europe. The Lancet Planetary Health, 7(4), e271-e281.

Gasparrini, A., Masselot, P., Scortichini, M., Schneider, R., Mistry, M. N., Sera, F., ... & Vicedo-Cabrera, A. M. (2022). Small-area assessment of temperature-related mortality risks in England and Wales: a case time series analysis. The Lancet Planetary Health.

Liu, J., Liu, T., Burkart, K. G., Wang, H., He, G., Hu, J., ... & Zhou, M. (2022). Mortality burden attributable to high and low ambient temperatures in China and its provinces: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Regional Health–Western Pacific.

Lee, J., & Dessler, A. E. (2023). Future Temperature‐Related Deaths in the US: The Impact of Climate Change, Demographics, and Adaptation. GeoHealth.

Gasparrini, A., Guo, Y., Hashizume, M., Lavigne, E., Zanobetti, A., Schwartz, J., ... & Armstrong, B. (2015). Mortality risk attributable to high and low ambient temperature: a multicountry observational study. The Lancet.

These estimates come from the Human Climate Horizons (HCH) — a collaboration between the Climate Impact Lab and the UN Development Programme.

At least when it comes to temperature-related deaths. They are, of course, still vulnerable to other impacts.

Note that the emissions from refrigerants are not included in the cooling estimates. It's for electricity use only.

When these are included, cooling-related emissions approximately double.

Great write up - I particularly appreciate the fact that it puts some numbers on the intuition I had about space cooling : a lot less energy hungry than heating and a potentially life saving technology.

The conclusion of the article is equally interesting, as it seems to suggest that not much progress has been made on cooling technologies, and that this domain is somehow overlooked by climate tech companies? Would you be able to share resources that elaborate on that point?

Great article. One crucial implication is that to save lives our absolute priority should be to ensure that poor countries get access to cheap and reliable electricity as a matter of urgency, so that they can install operate air-conditioners as well as heat their homes in winter. Currently policies of multinational institutions are preventing this by primarily financing intermittant renewable energy while avoiding financing of large hydro, fossil fuels and nuclear energy. Our experience in the west is that intermittant renewables do no provide cheap and reliable electricity because of the costs of dealing with intermittency and their highly dispersed nature. Instead of favouring certain types of electricity generation we should encourage countries to invest in whatever provides the cheapest electricity.