Do heat pumps work in the cold?

Efficiency declines with falling temperatures, but they still perform well in colder climates.

It would be a bit useless if your mode of heating only worked in warm climates, not cold ones. This is becoming a common pushback on electric heat pumps.

Here in the UK, a lot of the public is still skeptical and I’m sure it’s the same elsewhere.

In this post, I’ll look at the performance of heat pumps in different climates, and survey data on how satisfied users are with their installations.

First, a very quick reminder of what heat pumps are. I’ve written about them before if you want to dig into more details.

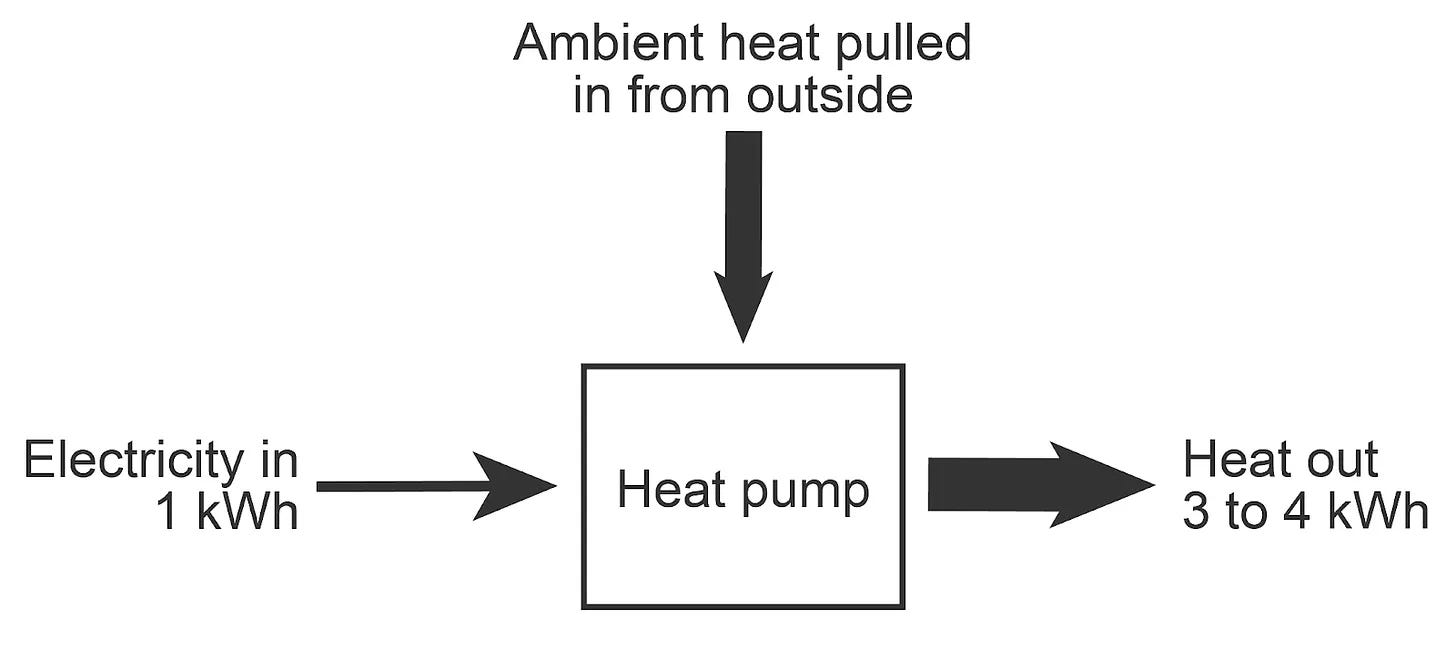

Heat pumps work a bit like refrigerators but in reverse. They capture heat from outside of the home – in the air, or the ground depending on the type. This heat warms a liquid refrigerant, turning it into a gas. Electricity is then used in the pump to compress this gas and release it at a higher temperature. This heated gas can then either be moved around the home in its gas form, or transferred to a hot water system.

The magic of heat pumps is that you get a lot more heat out than you put in from electricity. For every unit of electricity you put in, you can get up to 3 or 4 units of heat out. They’re about 3 to 5 times as efficient as gas boilers.

Heat pumps perform well in colder temperatures

3 or 4 units out for every unit of electricity in. That might be the standard efficiency at mild temperatures, but what about in the cold? Do they still work?

The first signal that the answer is ‘yes’ is looking at where heat pumps are already popular.

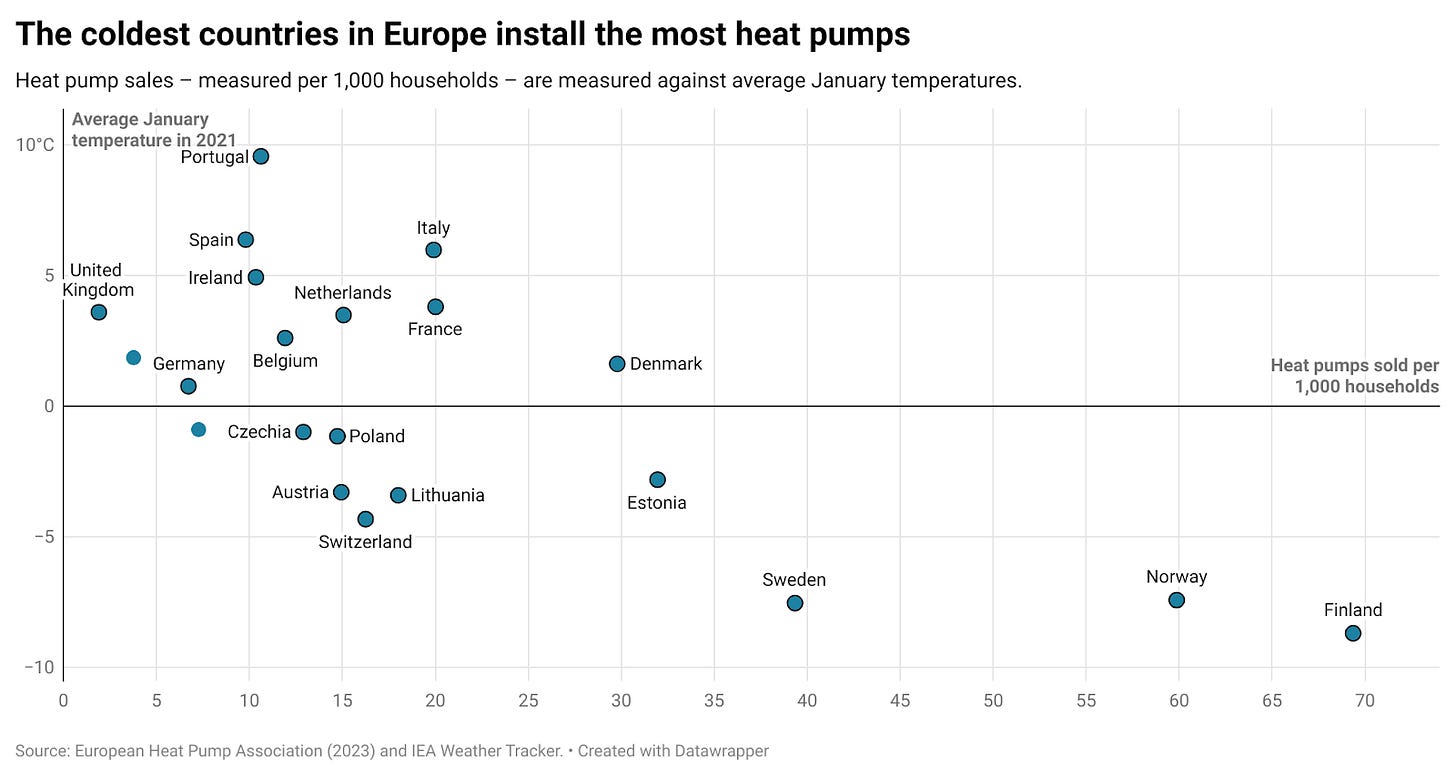

You’ll find many heat pumps in Alaska, where temperatures can get below -20°C in winter. Or in Europe, where Norway, Finland, and Sweden have the most heat pumps per million households. Below I’ve plotted heat pump sales (on the x-axis) against average January temperatures on the y-axis.1 It’s the coldest places that have the most installations.

But we don’t have to rely on simple correlations. We can also look at measured levels of performance in different climates.

In a study published in Joule, Duncan Gibb, Jan Rosenow, Richard Lowes, and Neil Hewitt, looked at data on 550 heat pump systems in Switzerland, Germany, the UK, Canada, the US, and Germany.2

Heat pump efficiency can be measured using a metric called the ‘Coefficient of Performance’ (COP). This captures the measure we looked at above: how many units of heat do you get out for every unit of electricity you put in? So, a COP of ‘3’ means you get 3 units of heat for every unit of electricity.

This study was focused on air-source heat pumps. Ground-source heat pumps typically maintain their high levels of efficiency, even in cold weather.

The performance of air-source heat pumps indeed falls when it’s colder. Their efficiency is typically driven by the temperature difference between indoor and outdoor conditions. When it’s colder outside, this temperature differential is larger. While their performance drops, they can still perform well.

Gibb and colleagues found that between 5°C and −10°C, the average COP was around 2.7. We get 2.7 units of heat for every unit of electricity we use. It also meets our heating needs at a much higher efficiency than gas boilers or electric radiators. These COP values ranged from 3.3 in Canada, to 2.5 in the UK, down to 2.4 in China. In other words, they can be effective everywhere.

As I’ll discuss later, there were a few systems in the sample that did have pretty low COPs. This is likely to be the result of poor installation, which is why having a large skilled workforce is so crucial if we’re to revamp the heating system in hundreds of millions of homes.

They can still work at extremely low temperatures, although they’re less efficient

What about heat pumps at extremely cold temperatures?

Heat pumps – designed for extreme cold – were also tested in locations that reached as low as -35°C. The COP was typically between 1.3 and 2. So, we’re still getting more heat out than we put in. The performance is lower than in ‘milder’ cold climates, but still sufficient in many circumstances. Some might choose small space heaters as a backup, but that shouldn’t be needed if the heat pump is fitted properly.

Users of heat pumps seem satisfied with them, even in older homes

You can also just ask people if they’re satisfied with their heat pumps.

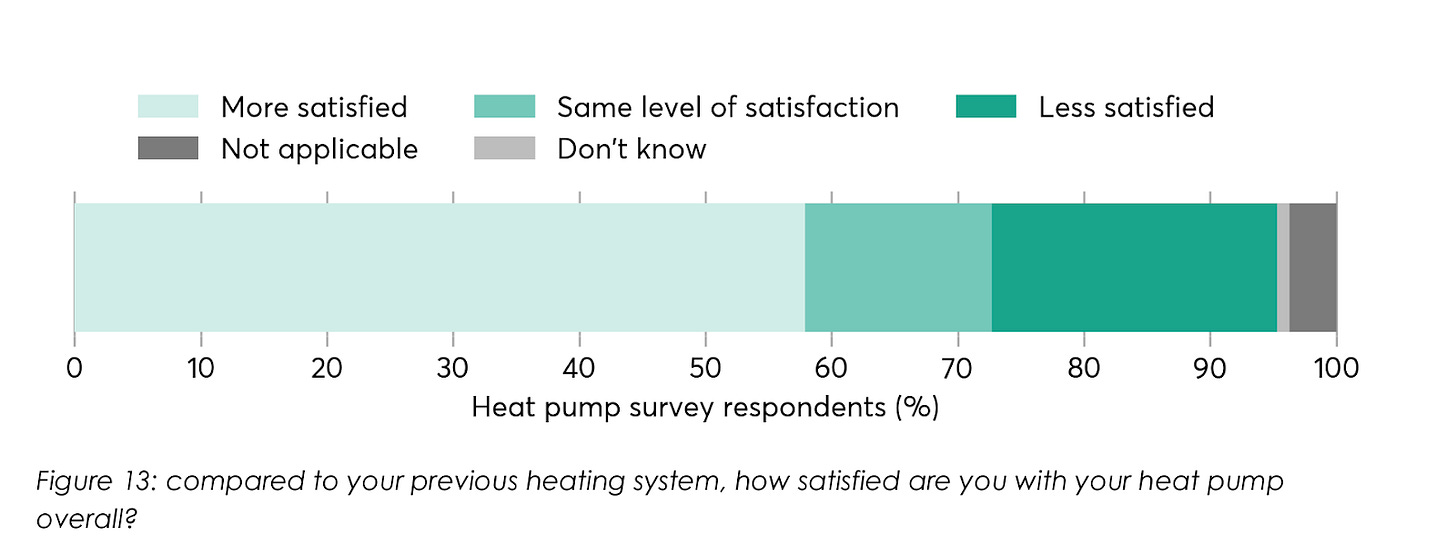

Nesta, interviewed more than 2,500 heat pump users in Britain to see if they were happy with their systems. Around three-quarters said they were happier – or just as happy – compared to their previous heating system. Those levels of satisfaction were comparable to those with a gas boiler.

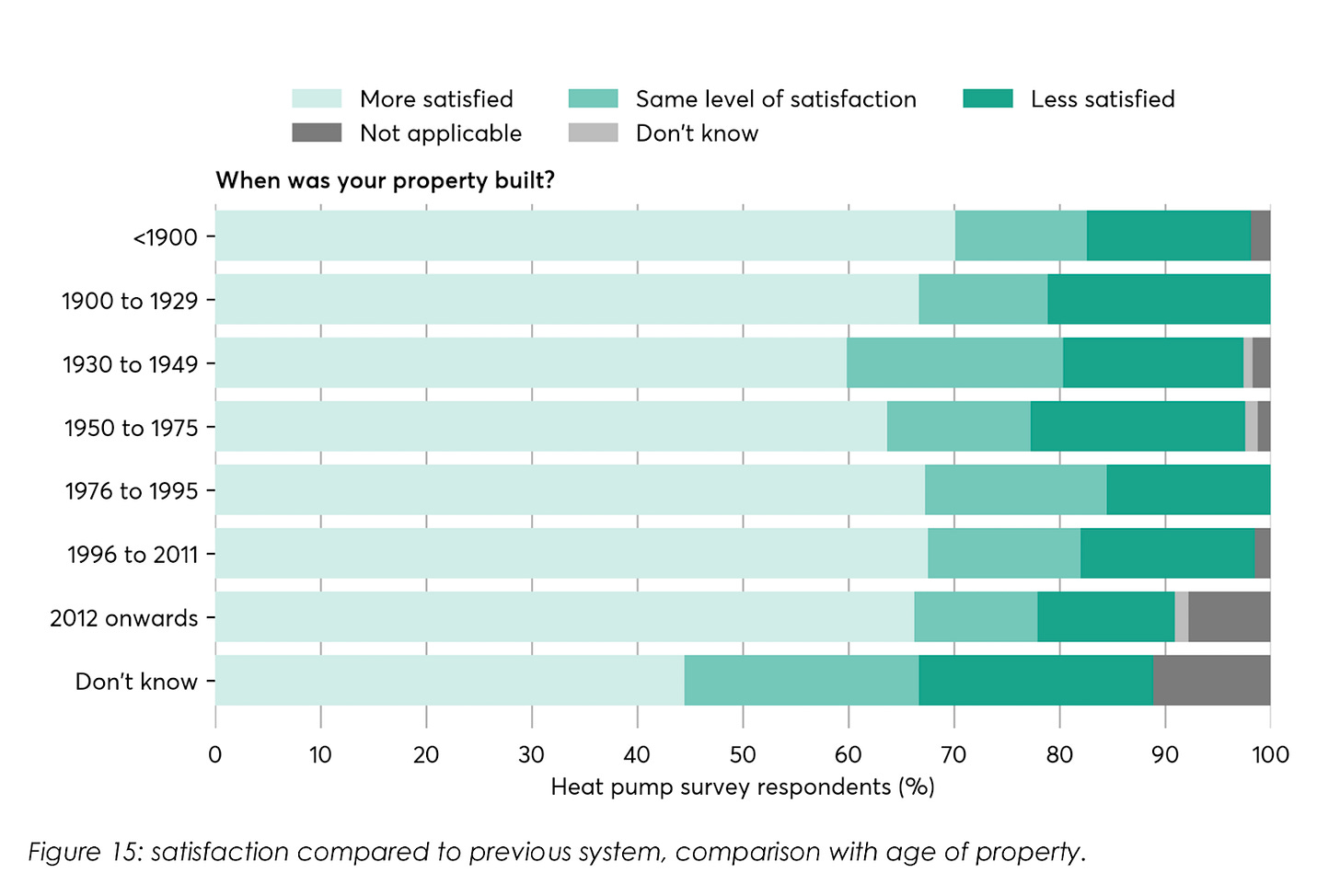

Do they work in old, leakier homes? There have been many headlines in the UK – not least from the head of Bosch, a heat pump manufacturer – saying that heat pumps don’t work in older, Victorian homes.

Heat pumps will work best with proper insulation. But that applies to every heating system.

The survey by Nesta included modern and older homes with heat pump installations. In the chart below you can see levels of satisfaction broken down by the age of the house. Users seemed happy, regardless of when the property was built. Even in homes built more than a century ago.

This suggests that heat pumps can work in older homes, especially with a skilled installer who fits the system properly.

Having skilled installers matters a lot

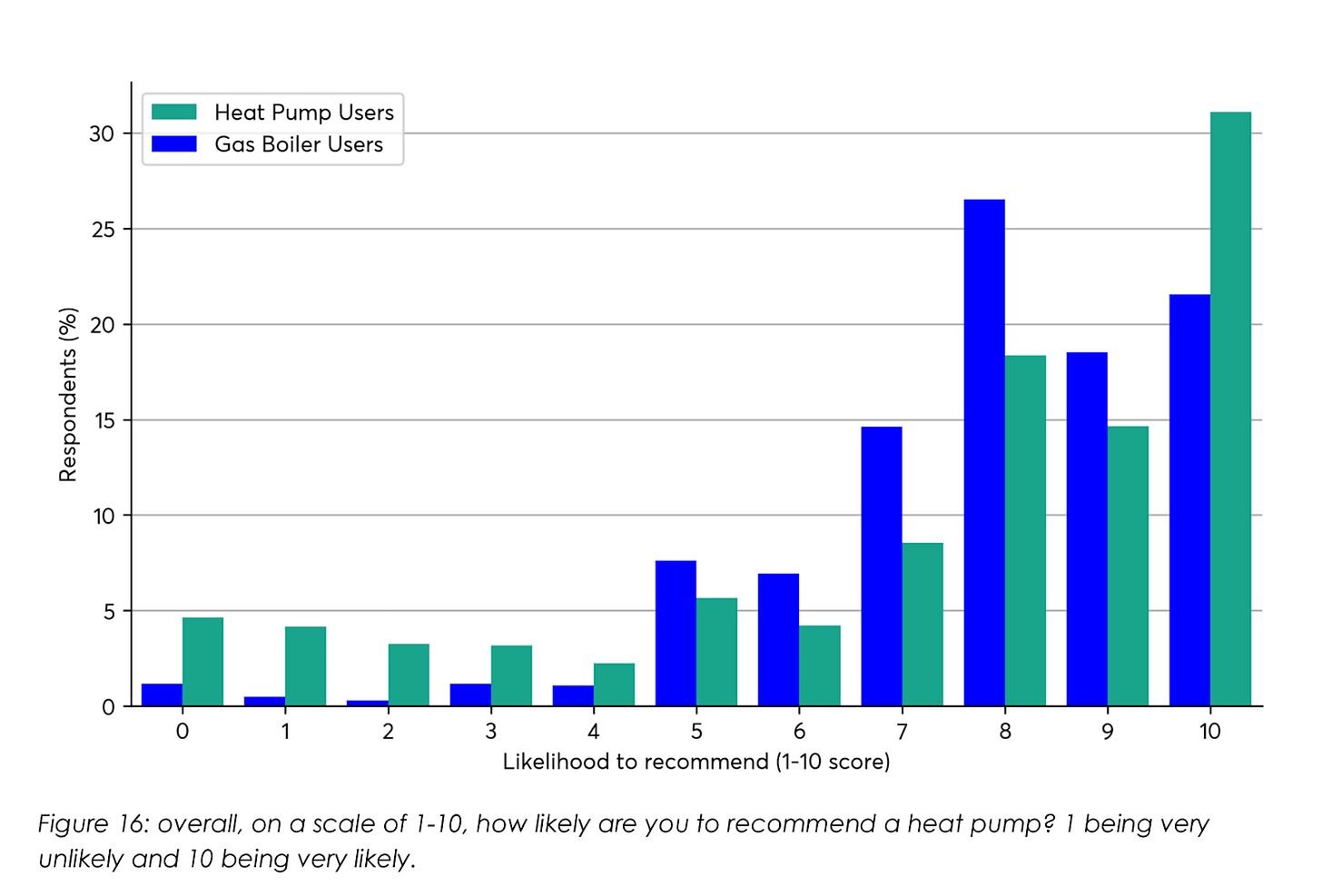

Nesta asked heat pump users to give a score out of 10 about how likely they’d be to recommend them to others. 31% gave the maximum score of 10. 64% gave at least 8.

That was about the same as gas boiler users.

However, there was much more variability for heat pump users, especially towards the bottom of the ratings. 17% gave a rating of less than 5. This was much higher than for gas boilers.

Most people with heat pumps like them, but around one-in-five don’t. That might be because heat pumps are still a novel technology, and some users aren’t yet comfortable with them. But another plausible explanation is that some users have experienced poor installations.

The UK – and I’m sure this applies elsewhere – does not have enough highly skilled installers. Heat pumps are more complex to install than gas boilers; they need a combination of skills including engineering, plumbing, pipefitting, and refrigeration.

If we don’t have enough people to install them, it’s not only a block on the speed of the transition to low-carbon heating, it also risks the reputation of heat pumps overall. If unskilled workers are installing botched heat pump systems, public perceptions will get even worse.

The data shows that heat pumps can work effectively, even in colder climates. It would be damaging if a minority of poor installations overshadowed the fact that most people with a heat pump are happy with them.

This data comes from the European Heat Pump Association (2023).

Temperature data comes from the IEA’s Weather for Energy Tracker.

Gibb, D., Rosenow, J., Lowes, R., & Hewitt, N. J. (2023). Coming in from the cold: Heat pump efficiency at low temperatures. Joule, 7(9), 1939-1942.

The reason why insulation is more important for heat pumps is because they slowly warm up your space with lower temperature heat. A strong current of high temperature heat is going to feel better comparably in a drafty house.

Heat pumps are measured not by COP in heating but by HSPF, which takes into account defrost efficiency and other items during heating. For operation in cooling mode SEER is the rated metric.

The failure to recognize thus detracts substantially from the article and the author's credibility. Plus ghe obvious failure the view the correlation between unit density and average winter ambient as subject to energy costs and subsidiaries and other factors is a serious omission. In Canada all of these factors come into play, particularly give our wide range of climate zones. The author needs to look further into the matter