The mineral monopoly: will low-carbon technology be controlled by a few countries?

The energy transition has been hailed as a path to energy security. Is this true, or do a few countries hold most of the world's minerals?

Many countries tried to boycott Russian goods when it invaded Ukraine last year. But this hasn’t been easy. Russia was the world’s largest fossil fuel exporter in 2021, and many countries – especially in Europe – have struggled to find alternatives.1 The war put our fossil fuel dependency in the spotlight.

🗺 Explore an interactive map of global:

– Coal exports

– Oil exports

– Gas exportsOne argument for decarbonisation – as if climate change and air pollution weren’t enough – is that it would give countries energy security. They wouldn’t have to rely on others for fossil fuel supplies.

Some people have pushed back on this pipe dream. They say that a low-carbon energy system wouldn’t solve this: we’d still be dependent on a handful of countries for the minerals we need for solar panels, wind turbines, batteries, and electric vehicles. We’d just substitute one dependency for another.

But is this true? Are the world’s minerals concentrated in only a few countries?

In this article, I look at the numbers on mineral production and reserves by country. This data comes from the US Geological Survey (USGS).2

My aim is to get us grounded on the numbers. There are lots of other factors we need to consider, including the cost, social and environmental impacts of mining. I'm not tackling those topics here; not because they’re not important but because there’s only so much you can pack into a single post.

I first want to show where the world's mineral resources are. What we do with them (if anything) is a separate question.

A few countries are very rich in minerals

Every mineral we’ll go through has a different set of top countries. Some countries are rich in only one mineral. Indonesia, for example, is the leader in nickel but doesn’t have large reserves of much else.

But there are a handful of countries that dominate across many minerals. These are China, Australia, Chile, Brazil, the United States, Russia, and South Africa.

In the table, I’ve shown the percentage of the world’s reserves that each country has.

To clarify what a reserve is: it’s a deposit of a mineral that has been studied, and is assessed to be technologically and economically feasible to extract under current market conditions. The amount of known reserves can change over time, as we discover new ones, technologies improve, and markets change to make it economical for them to be mined.

Low-carbon mineral dependency is not the same as fossil fuel dependency

There are several minerals where reserves are highly concentrated: molybdenum, vanadium, and chromium are prime examples. A few countries have almost all of it.

But, for most, there is a range of countries – geographically and politically diverse – that have sizable resources. These countries are not yet mining the mineral, but they could.

We should also acknowledge that fossil fuel dependency is not the same as a dependency on low-carbon technologies. The surge in demand for minerals for low-carbon tech will be temporary. The transition comes with an initial scale-up stage to build the panels, turbines, and batteries. Think of it like a capital cost. The ‘running’ cost is basically zero. Your negotiator is not Russia, China, or the US, it’s the sun and the wind.

There is also the opportunity to recycle or repurpose them at the end of their life. Recycling rates vary from mineral to mineral, but recovery methods will continue to improve – especially if countries invest in these technologies as a way of becoming more self-sufficient.

This is different from a dependency on fossil fuels. That needs an endless supply of coal, oil, and gas. And you can’t recycle it at the end of its life. The running costs are high, and you’re completely tied to those that have the fuel you need. Play ball or the lights go out.

Production and reserves, mineral by mineral

I’m going to go through each mineral one by one, looking at each country’s share of global production and its share of known reserves.

With so many minerals, this post gets pretty long. Feel free to jump to any of them by clicking on the link.

Lithium • Cobalt • Copper • Nickel • Silver • Manganese • Silicon • Molybdenum • Zinc • Chromium • Graphite • Vanadium

Lithium

What is it used for? Electric vehicles and battery storage.

Global production in 2021: 105,000 tonnes.

Global known reserves in 2021: 27 million tonnes.

Geographical concentration: Lithium is the only mineral on the list that the USGS also provides data on resources, alongside production and reserves. ‘Resources’ are estimates of the total amount of a mineral in discovered and undiscovered deposits.

Lithium production is dominated by a few countries: Australia, Chile, and China account for almost 90% of the global total.

Reserves are slightly more diversified. But resources are even more so: a large number of countries have deposits of lithium that haven’t been assessed yet, or are not considered technologically or economically feasible to extract at the moment.

Cobalt

What is it used for? Electric vehicles and battery storage.

Global production in 2021: 170,000 tonnes.

Global known reserves in 2021: 7.6 million tonnes.

Geographical concentration: Most of the world’s cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Child labor, slavery, and human rights abuses have been widely documented in DRC’s cobalt mining industry. This has put increasing attention on EV developers to build battery technologies less dependent on cobalt.

But, global reserves are more diverse than current production. Many more countries – such as Australia – have reasonably large reserves of cobalt available.

Copper

What is it used for? Solar PV, wind energy, concentrating solar power, geothermal, geothermal, hydropower, nuclear, electric vehicles, battery storage, and electricity grid expansion.

Global production in 2021: 21 million tonnes.

Global known reserves in 2021: 880 million tonnes.

Geographical concentration: Copper mine production is reasonably diverse: many countries across the Americas – both North and South – extract it. However, copper refining is much less so: China accounts for a much larger share, making up almost 40% of the total.

Reserves are even more widely distributed. Many countries across South America have large reserves, as does Australia and Russia.

Nickel

What is it used for? Wind, nuclear, geothermal, concentrating solar power, electric vehicles, and battery storage.

Global production in 2021: 2.7 million tonnes.

Global known reserves in 2021: 95 million tonnes.

Geographical concentration: Indonesia and the Philippines account for half of global nickel production.

Australia and Brazil are the two countries with large reserves that produce much lower volumes of the global total.

Silver

What is it used for? Solar photovoltaic.

Global production in 2021: 24,000 tonnes.

Global known reserves in 2021: 530,000 tonnes.

Geographical concentration: Silver production and reserves are both geographically diverse.

Manganese

What is it used for? Wind energy, concentrating solar power, nuclear, electric vehicles, and battery storage.

Global production in 2021: 20,000 tonnes.

Global known reserves in 2021: 1.5 million tonnes.

Geographical concentration: South Africa, Gabon, and Australia produce most of the world’s manganese. Reserves are highly concentrated in a handful of countries: combined, South Africa, Australia, and Brazil hold around 80% of them.

Silicon

What is it used for? Solar PV, electric vehicles, and battery storage.

Global production in 2021: 8.5 million tonnes.

Global known reserves in 2021: Widely abundant.

Geographical concentration: China produces most of the world’s silicon. This is not a reflection of resources. Silicon is widely abundant. The USGS does not provide resource information for countries because, as it states, “the reserves in most major producing countries are ample in relation to demand. Quantitative estimates are not available.”

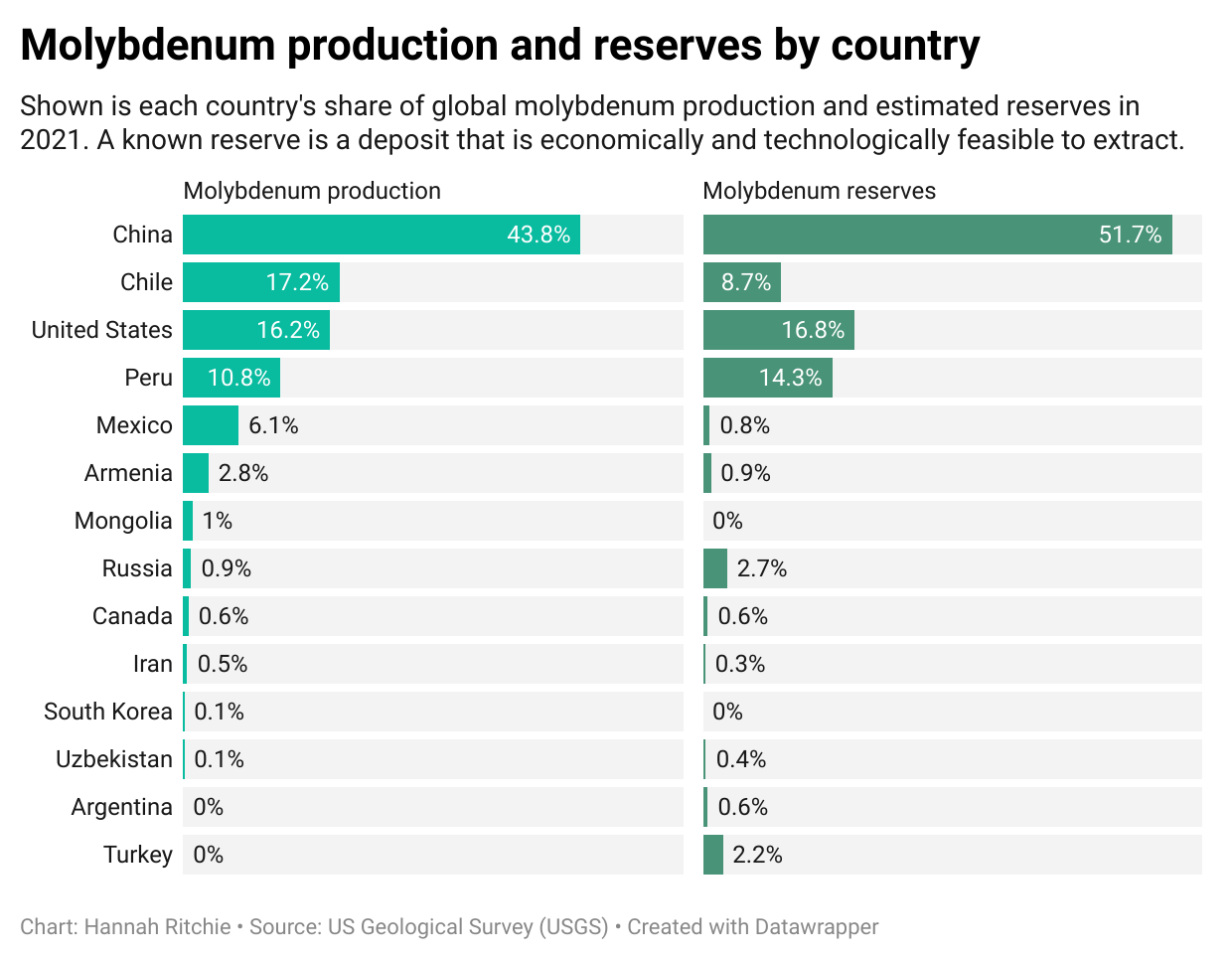

Molybdenum

What is it used for? Wind energy and nuclear.

Global production in 2021: 300,000 tonnes.

Global known reserves in 2021: 16 million tonnes.

Geographical concentration: Molybdenum production and reserves are closely aligned. The countries with the largest reserves are also the largest producers.

Reserves are highly concentrated though: China, Chile, Peru, and the US account for around 90% of the total.

Zinc

What is it used for? Wind energy, concentrating solar power and hydropower.

Global production in 2021: 13,000 tonnes.

Global known reserves in 2021: 250,000 tonnes.

Geographical concentration: Zinc production and reserves are widely distributed across world regions.

Chromium

What is it used for? Geothermal, concentrating solar power, wind, and nuclear.

Global production in 2021: 41,000 tonnes.

Global known reserves in 2021: 570,000 tonnes.

Geographical concentration: A small number of countries have known reserves of chromium. Kazakhstan has the largest known reserves, at 40%, but produces just 17% of the world's total.

India also produces much less than its share of reserves: 7% production versus 18% of reserves.

Graphite

What is it used for? Electric vehicles and battery additions.

Global production in 2021: 1 million tonnes.

Global known reserves in 2021: 320 million tonnes.

Geographical concentration: China produces almost 80% of the world’s graphite.

However, it doesn’t have to be this concentrated. China has just 23% of known reserves, and a large number of countries have deposits – even if they are small, they could be sufficient to meet domestic demand (plus some excess to export to other countries without reserves).

Note that graphite reserves data was not publicly available for some countries – these are shown as blank.

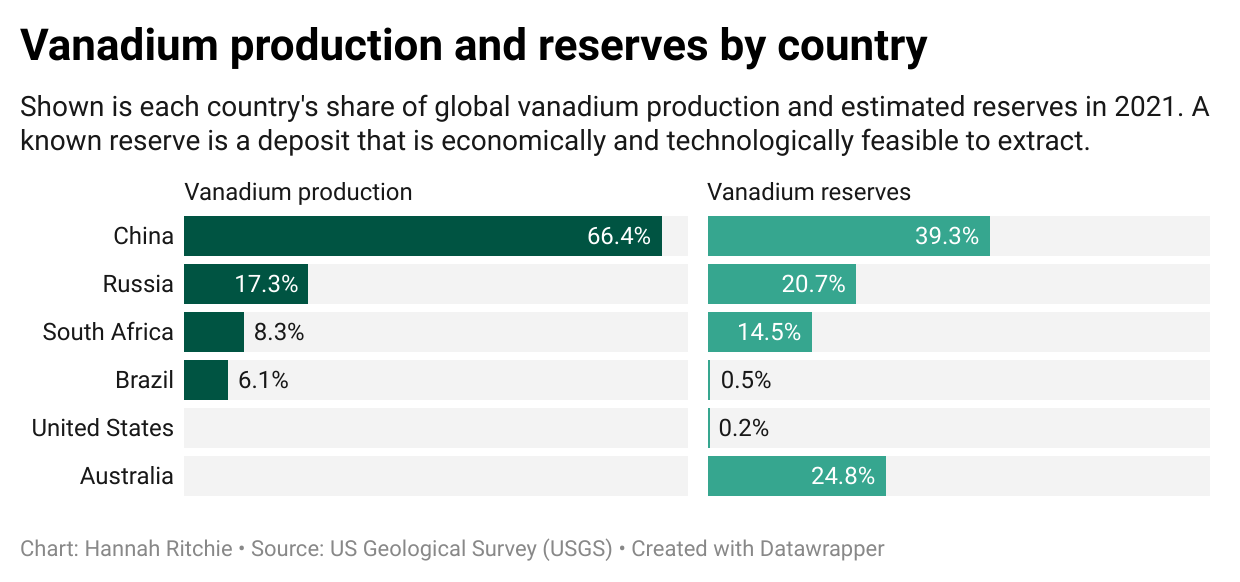

Vanadium

What is it used for? Battery storage.

Global production in 2021: 110,000 tonnes.

Global known reserves in 2021: 24 million tonnes.

Geographical concentration: China produced two-thirds of the world’s vanadium in 2021. Global production and reserves are concentrated in just a handful of countries: China, Russia, Brazil, South Africa, and Australia.

The only way to diversify is for Australia to start producing vanadium: it holds one-quarter of the world’s known reserves, and currently produces nothing.

IEA (2022), National Reliance on Russian Fossil Fuel Imports, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/national-reliance-on-russian-fossil-fuel-imports

You can find annual reports for each commodity from the USGS here: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/national-minerals-information-center/mineral-industry-surveys#S

And yes, I copied all the numbers from PDF (!) documents of the USGS reports.

The USGS reports all of these figures in absolute numbers: tonnes. I have converted this into each country’s percentage of the global total.

I'm glad you've corrected some of the figures (copper, silver) for production and reserves, but several are still incorrect. I haven't checked them all (I'm not paid to do this), but I can tell you that those for manganese and zinc are incorrect (wildly underestimated).

It's also worth noting that several of these elements have large scale uses that will be in competition with their use in RE technology (e.g. chromium and nickel in stainless steel). Secondly, I do not think that the figures for graphite are relevant. I would be surprised if natural graphite, which is difficult to purify and mainly used in powder form in lubricants and as a mould release agent, is used in EV technology. Synthetic graphite is already used in large quantities in batteries and for electrodes in electric motors and the aluminium and steel industries and as a moderator in some nuclear reactors (Chernobyl), as it can be made into (very) large lumps and is purer and therefore a better conductor than the natural form. Production (1.9 million tonnes) is already larger than the figure of 1 million tonnes mentioned above and I expect production will be concentrated in locations where the metallurgical industries are based.

https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/synthetic-graphite-market#:~:text=The%20global%20market%20for%20synthetic,Ltd.

Thank you! Big fan of your posts. As a Kiwi, it’s interesting to see the new Australian govt becoming the clean energy behemoth it always should have been