The world is on track for record harvests this year

What do the latest projections expect for global food production and yields of different crops?

It’s not uncommon for people to tell me that global food production is already collapsing due to climate change. They are then surprised to hear that we typically hit record harvests year after year (even as things get hotter).1

But there are large and genuine risks of climate change to agriculture — I’ve written about this a lot, and it is probably my biggest concern when it comes to climate impacts — and there’s no guarantee that rising productivity continues.

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) tracks agricultural conditions across the world and publishes monthly updates on its outlook for production and yields for the year. I check this often to see how things are looking.

I posted an update on this last year, so here is the 2025 version.

The data I’m relying on for this summary is the USDA projections for the year based on its latest update (September 2025).

Note: These are projections based on the latest assessment of growing conditions and planting areas. For various reasons, this could change in the next few months.

Corn, wheat, soybeans and rice are on track for record harvests

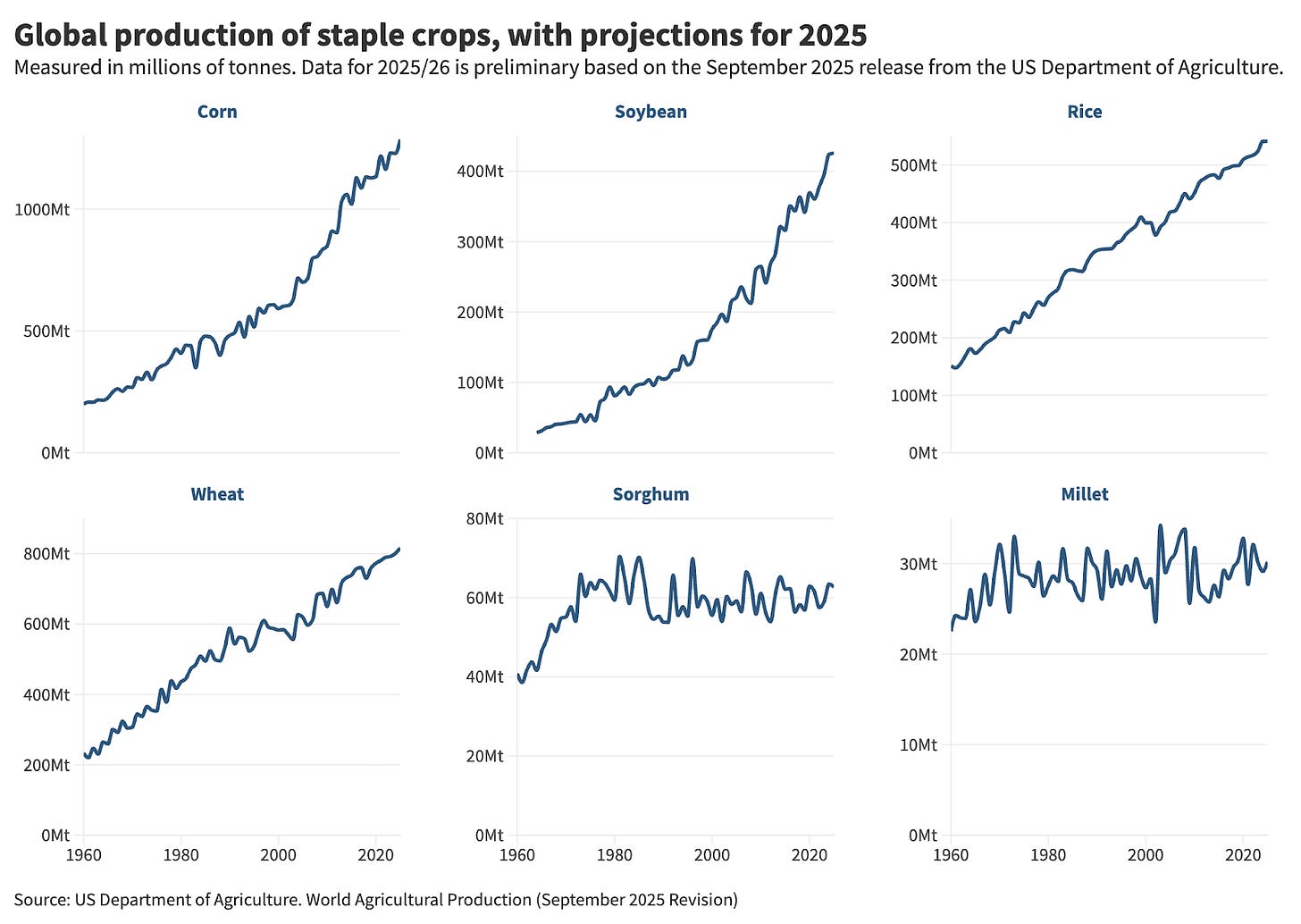

Here’s the total amount of staple crops the world has produced since 1960. The last year — 2025 — is the USDA’s latest projection.

Most crops, with the exception of sorghum and millet, have seen steady increases over the past 60 years, and that trend is expected to continue this year.

Corn (maize) and wheat, in particular, have seen large increases this year. Soybeans are also expected to see a record. For rice, the rise is very small — basically the same output as last year (which was also a record).

Sorghum and millet — lesser-known but important staple crops in the tropics — continue with their regular pattern, fluctuating up and down without much sustained growth at all. This is concerning for food security, especially across Sub-Saharan Africa.

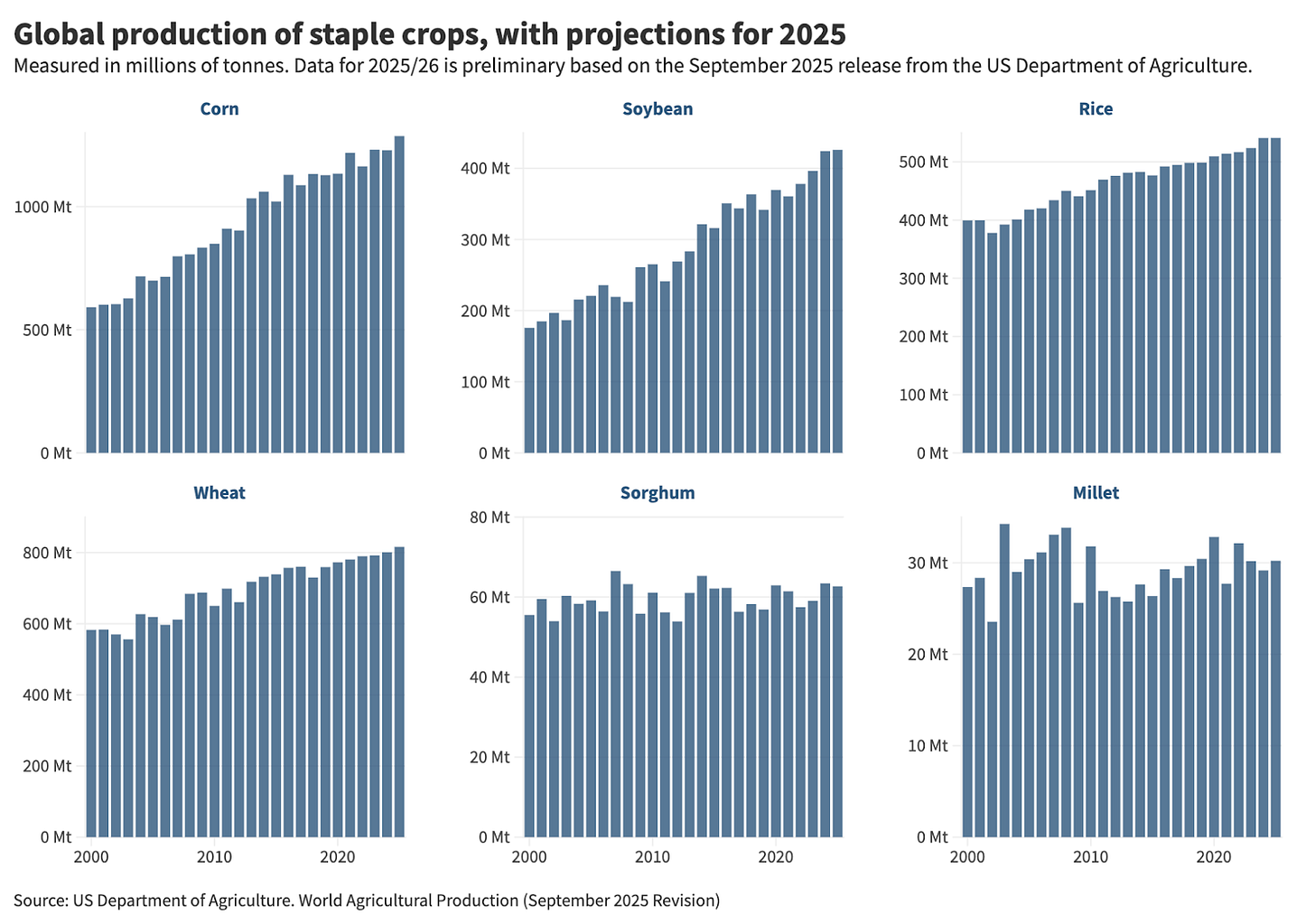

In the chart below, I’ve zoomed in on production figures since 2000 to see the recent data more clearly.

Again, you see the very large jump for corn in 2025; a reasonable jump for wheat, but much smaller increases for soybean and rice.

Global yields of staple crops are also expected to reach an all-time high

It’s also important to look at crop yields. Producing more food from higher yields means using less land for farming (and the benefits that come with it), and it also means better returns for farmers.

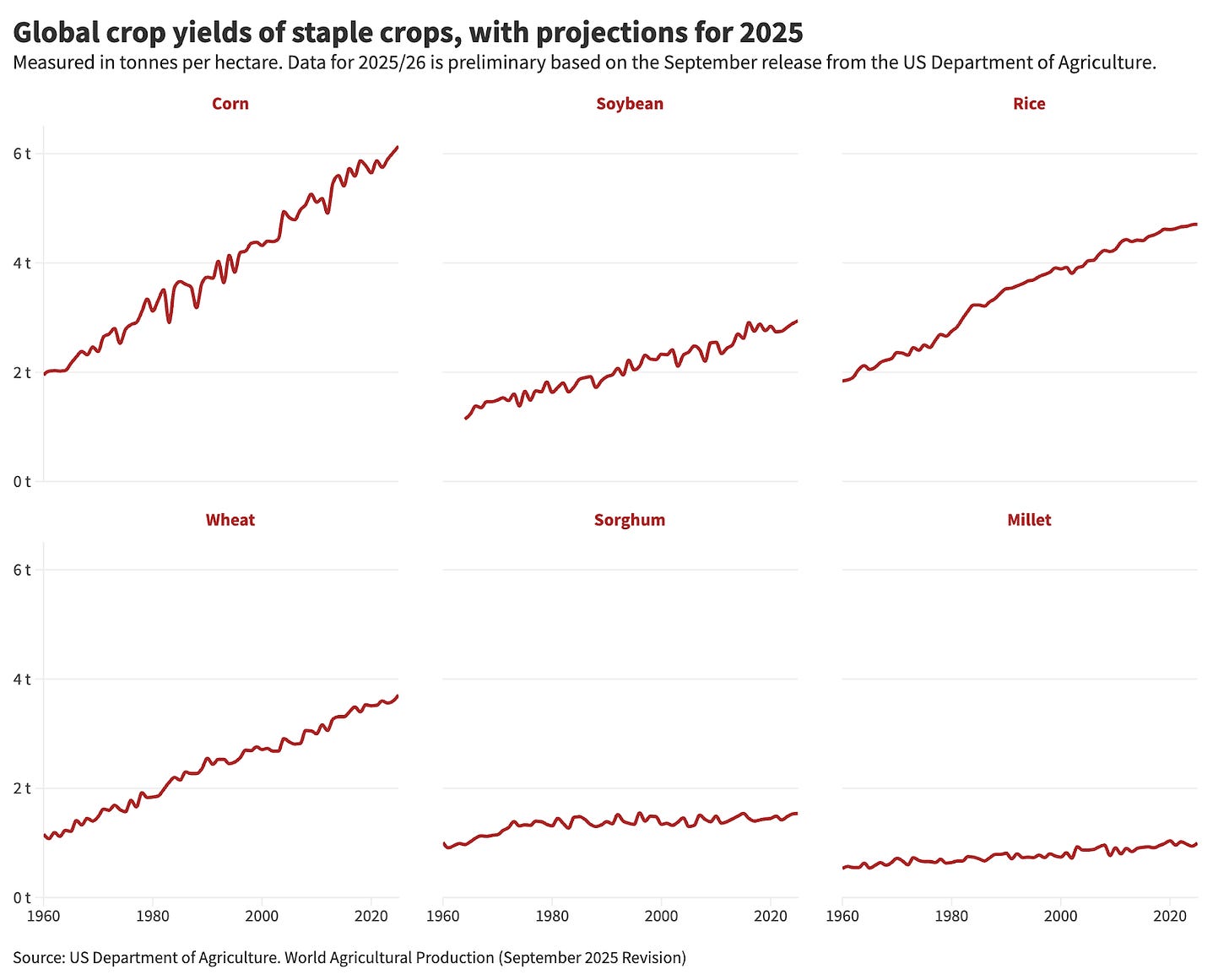

Corn, wheat, soybeans, and rice are all expected to see record yields this year. You can see this in the chart below.

Again, the jump for corn and wheat is fairly substantial. However, the rise in soybeans and rice is also more noticeable this time. Their increase in production was extremely marginal, so the fact that yields have increased quite a bit means that the area of soybean and rice crops planted is down from the previous year.

Again, you can see how poor the yields for sorghum and millet are. These are crops that have not received the same R&D investment as others, and it shows.

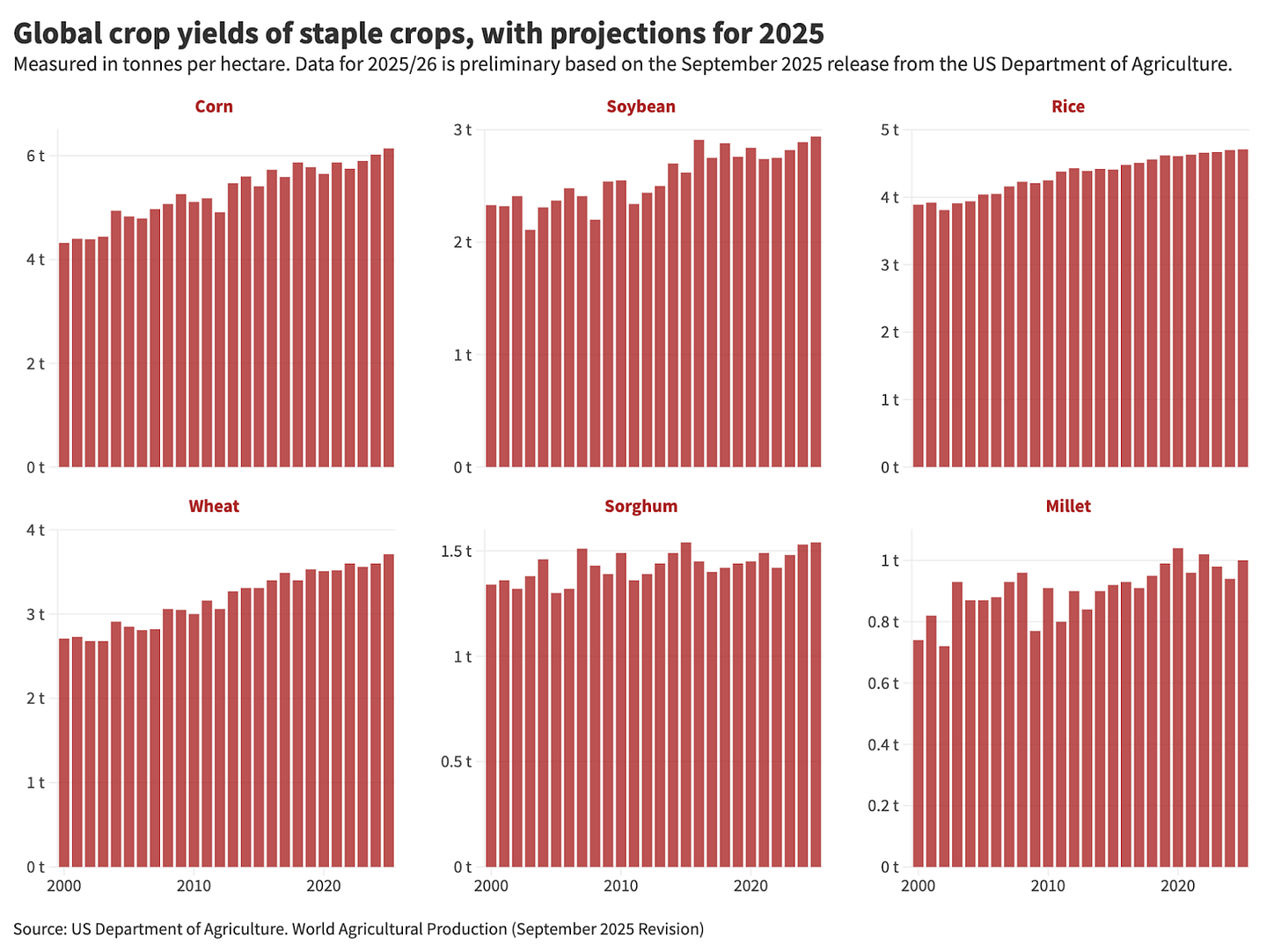

Here’s the data, just from the year 2000, which makes the recent changes easier to see.

What’s happening with non-staple crops: oils, cotton and coffee?

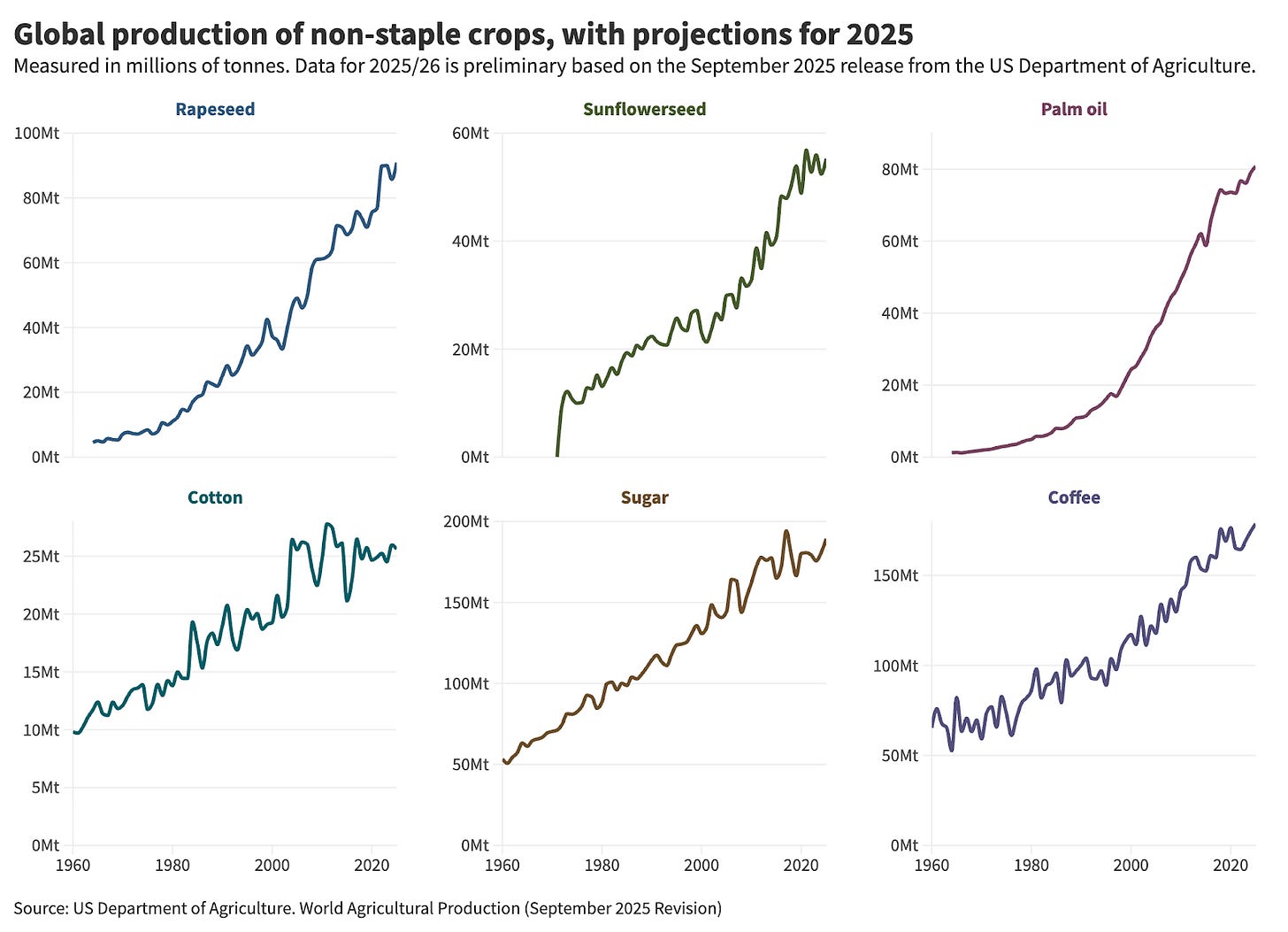

What about some other key crops that aren’t cereal or pulse staples?

Here — as you might expect for a wide range of crops — the picture is a bit more mixed. Below, I’ve shown the production figures for some oilseed crops, such as sugar, coffee, and cotton.

Rapeseed, palm oil, and coffee are all on track for record harvests. Sunflowerseed, cotton, and sugar are not.

As you can see, production figures fluctuate quite a bit from year to year, partly due to changes in weather conditions (i.e. supply) and changes in the market (i.e. demand).

Again, these are current projections to the end of the year, and subject to change. But the current data points towards strong agricultural output this year.

This summary of global food production obviously doesn’t reflect farming conditions and output everywhere. The USDA provides more in-depth coverage of countries or regions where production is up and where it’s down from previous years.

Large disruptions in national or regional production can occur without major changes to global production. This is one reason why a global interconnected food system can be much more resilient than local ones. Every year, some farmers get extremely poor harvests. But these losses can often be balanced out with surpluses elsewhere. This is very different from our food systems of the past, when a bad harvest inevitably meant hunger.

This is because even as increased temperatures have negative impacts on some crops, other improvements and enhancements in crop production have outpaced many of those impacts.