Deforestation in the Amazon has halved in the last few years

Lula da Silva is making progress, just like he did during his previous presidency.

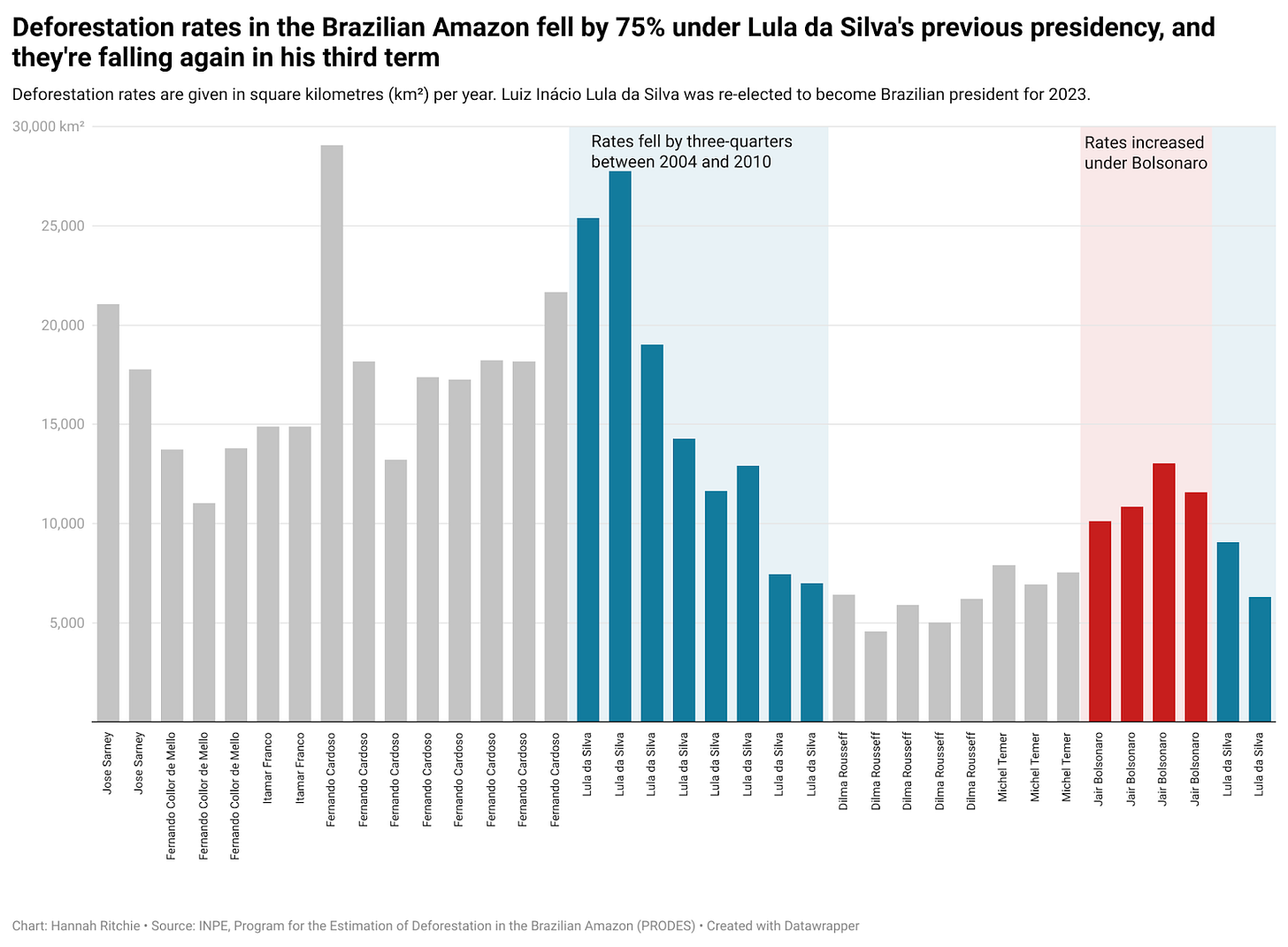

In my book (published at the start of this year), I included this chart of deforestation rates in the Brazilian Amazon since the 1980s. I also wrote about it on my Substack.

Deforestation rates had doubled under Jair Bolsonaro, and things were looking bleak. But at the time of writing, Lula da Silva had just been re-elected and I said that this should give us some hope of a turnaround.

This has happened. The latest satellite data from Brazil’s space agency, INPE, has confirmed a second consecutive year of declining deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon.

Here’s a quick update of the charts showing the trends since 1988.1

First, you can see that rates fell in 2023 and have fallen by another third in 2024 (shown in green bars below). That means rates have roughly halved since 2022.

This is not the first time that Lula has got serious about deforestation. Rates fell by 75% during his first two terms, in the first decade of the 2000s.

In the chart below I’ve shown the same data, but with the sitting president listed for every year. In blue, you can see the initial drop in deforestation rates under Lula. In red, you can see the rise under Bolsonaro.

Now, the Amazon is still losing forest — deforestation rates are positive, not zero. And this is at a time when compounding pressures of climate change (and in the last few years, the El Niño) have made these ecosystems increasingly unstable.

But to expect that Lula da Silva and his environment minister, Marina Silva, would get deforestation to zero overnight would be naive. They are making significant progress. Ending deforestation by 2030 — which they’ve pledged to do — will not be an easy task, but they would probably be my “top picks” to get it done.

One lesson from the long-term data is that leadership and governance on this issue are crucial. It’s worth keeping in mind that Lula’s current term ends in 2026, and it’s still an open question as to whether he will run for re-election. That means the final four years to the ‘2030 target’ could very well be under a different leader, regardless of whether a left-leaning candidate is elected.

While the current trend is positive, there’s no room for complacency. The mid-2020s could easily be a repeat of the mid-2010s when record lows were followed by a decade of climbing deforestation rates.

But as we see out 2024, we should take some hope from the last few years of progress and be determined to carry it into 2025.

👋 This will be my last post of the year. Thanks to you all for following along as I crunch through the numbers and try to understand how the world is changing.

In the new year, I plan to kick things off with a three-part series looking at the data on climate impacts from this year, focusing on wildfires, disaster deaths, and food production (which aren’t covered in the news as much as record temperatures and emissions). I’m still waiting for the final data, but it should be ready in early 2025.

Wishing you all the best for the year ahead.

Note that year totals tend to run from August to July; so the data for 2024 runs from August 2023 to July 2024. This reporting period aligns with the typical dry season in the Amazon, which is when deforestation is most visible and detectable by satellites.

You can read the INPE’s technical note here (it’s in Portugese).

Some positive news at last - lets hope the trend continues. Thank you Hannah for all your informative posts this year - I look forward to them

Just a side comment: the linked PDF at the end is not in Spanish, but Portuguese (the language of Brazil)