What do Americans think about electric cars?

Many are sceptical of the climate benefits, and concerned about costs, but still expect to buy one in the next decade.

Energy headlines at the moment are dominated by discussion around Tesla’s future pathway – should it focus on a high-volume mass-market car or go all-in on autonomous robotaxis – the increasing pressure from BYD and other Chinese companies, and somewhat disappointing electric car sales in the US in the first quarter of this year. Note that sales are still up on last year, but the growth rate has certainly slowed.

I wanted to understand how Americans think about electric cars, and why they might be reluctant to make the switch.

Below I’ll take a look at data published by the Potential Energy Coalition. This is based on a range of national surveys and messaging tests, with inputs from nearly 60,000 people.

It’s worth noting that Americans are some of the most reluctant EV adopters across the world. In 2022, just 8% of new cars sold were electric.1 That’s far lower than the global average (14%) and way lower than in the EU (21%), UK (23%), China (29%), and enthusiasts such as Norway.

You can see these comparisons – based on data from the International Energy Agency – in the chart below. We’re still waiting for new IEA figures to come in for 2023, but I expect the overall differences between countries will be similar.

As we’ll soon see, there is a large partisan divide in attitudes to EVs. But, interestingly, in a poll conducted by the University of Maryland and the Washington Post, the same share of Republicans and Democrats owned one.

This is all to say that the US is one of the toughest markets to crack. If things really get moving there, we can be much more confident about uptake in other countries.

Most Americans think they will buy an electric car in the next 10 to 15 years

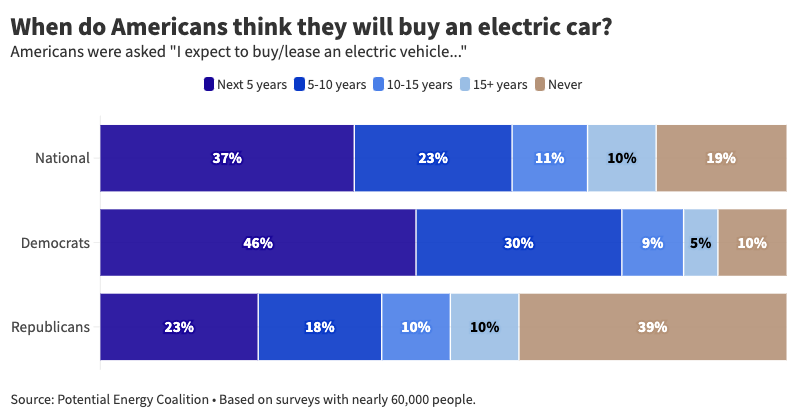

The survey asked Americans if they expect to lease or buy an electric vehicle in the future and when they think this will happen. They had the option of choosing “Never”.

Over a third (37%) expected to lease or own one in the next five years. 60% in the next 10 years. And around one-fifth said they would never have one.

The results are shown – broken down by Democrats and Republicans – in the chart below. Three-quarters of Democrats thought they would have an EV in the next 10 years. Republicans were much less enthusiastic, which will be a recurring theme for the rest of this article.

Still, more than 40% said they would lease or own an EV in the next decade. The same share said they would never have one.

The one downside to this question is that it asked whether Americans expected to own one, not whether they wanted to. Some might have said they would own an EV in the next 15 years because they would have no other option. Maybe they anticipate that new gasoline cars will be banned (which looks likely in some states) or carmakers will stop producing them.

In that sense, it’s not fully reflecting their attitude to EVs, but their expectations for where the car industry is heading.

What do Americans think about the benefits of electric cars?

Electric cars are becoming more popular, but there is still a lot of resistance among Americans. What are they skeptical about?

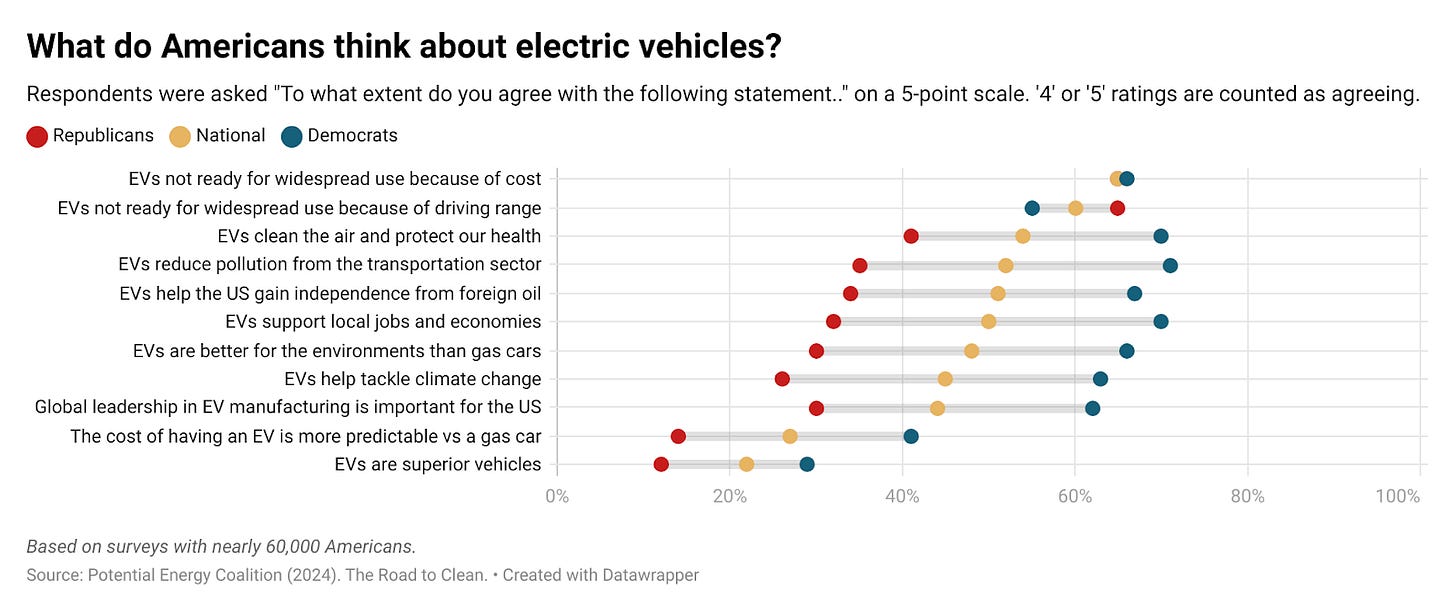

Potential Energy Lab asked the public whether they agreed – on a 5-point scale – with a range of statements. A score of “4” or “5” was counted as “agreement”. Note that this doesn’t necessarily mean that everyone else disagreed. Many people could have voted “3” – I’d frame this as a “don’t know” or “neutral” response.

The results are shown in the chart below (apologies for the density of information – if you want to explore the chart in more detail I’ve put it online via Datawrapper here). Again, it’s split by Democrat and Republican responses.2

There’s a lot going on there, so I’m going to zoom in on a few points.

Cost

This was the one question where Republicans and Democrats were in complete agreement. Up-front cost of EVs has been the biggest barrier to adoption. This matches with other polls, where the purchase price has been the main concern. Two-thirds said that the purchase price of an EV was higher, in a poll conducted by the University of Maryland and the Washington Post.

This is changing quickly though. The cost of new EVs is tumbling, and will likely reach price parity in the next few years. With the US tax credit from the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), EVs will soon be just as cheap. This is particularly true for car leasing, where large up-front costs are not an issue.

Range

60% have range anxiety, and think EVs are not ready for widespread use for this reason. The range of an average electric car is now more than 220 miles. Many high-end EVs are pushing over 400 miles. The average US driver travels around 30 miles per day. So a single charge should cover Monday to Friday driving for most people.

The anxiety, then, is for more rare and longer journeys. A large build-out of improved charging infrastructure will be needed to address those fears. Even then, it will probably take some time before drivers get the confidence that chargers will be there when they need them.

Climate

Less than half think electric cars are better for the climate. Pretty damning, considering there is strong consensus that EVs have a lower carbon footprint (even when the electricity mix is pretty heavy in coal).3 Electric cars are certainly better for the climate in the United States. We are clearly not doing a good job of explaining this to the public.

Republicans scored particularly low on this, with less than 25% agreeing. Democrats were also surprisingly low: less than two-thirds agreed that “EVs help tackle climate change”.

Clean air and environmental impact

The results were similar-ish for EVs cleaning the air, reducing pollution from transport, and being better for the environment. Around half said this was true. Again, the evidence is very clear for the first two: clean air, and reducing pollution. I wrote about the pollution benefits of electric cars in a previous article.

“Better for the environment” always seems like a fuzzy question to me. Does it need to be better for the environment on every metric? If it reduces carbon emissions and air pollution, but uses more water, is it better or worse for the environment?

Still, I expect many respondents – in addition to not believing it is better for the climate and pollution – picture the mining of critical minerals, and assume it’s worse than gasoline.

I’ve written a lot about mineral demand, looking at the mining requirements, and human rights abuses. The amount of materials we’ll need to mine will probably go down in a low-carbon transition, even when we account for ore concentration and waste rock. But, requirements for transport on its own (without electricity) actually go up a little when we include waste rock. On this one metric, then, you might argue that EVs are not “better for the environment”. But it seems odd that this would completely outweigh the other environmental benefits they bring. Again, it’s not a very clear question.

Local jobs and independence from foreign oil

Americans were pretty unsure on these questions. I would guess that many see the transition to EVs as moving from “homegrown gasoline car manufacturing in the US” to a “reliance on Chinese manufacturing and supply chains”.

In the survey by Potential Energy, over half of Americans thought that purchasing an EV primarily benefits China.

It’s true that China dominates global battery and mineral supply chains. The US is trying to push back with a drive for domestic production, high import tariffs, and the exclusion of Chinese imports from tax credits. Still, I’m sure many see this as clear evidence that EVs are a risk to US jobs, the economy, and its independence.

Having the freedom to choose is important

One of the main takeaways from the Potential Energy Coalition report is that choice really matters. No one wants their options to be limited. No one wants to be told what to buy, or what car to drive.

The winning narrative from that report (shown in the figure below) is that “Everyone, everywhere should have the choice to make their next car a clean car”. The focus is on clean, affordable, and practical. No surprise really: make EVs affordable and easy for people to switch, and they’ll do it.

But giving people the active choice to make the switch seems to be important. That pushes us towards carrots, not sticks. People don’t like bans or mandates. They do like tax breaks and incentives for clean energy.

This is a dilemma I might write about in a future post, as it extends well beyond EVs. My general mentality around these technologies is that if you build good, affordable products – and give them adequate support – people will make their switch on their own. This approach is more popular among the public too. The problem is speed. Will these changes happen fast enough without also implementing sticks – bans, mandates, and restrictions? I’m not sure. Probably not.

The ideal approach is probably some combination of the two. But how to achieve this while maintaining public support on both sides of the political aisle is going to be a struggle.

This includes fully-electric and plug-in hybrids.

Note that Independents are not shown for clarity. That means the national average is not always the simple average of Democrats and Republicans; Independents can skew the average a little.

Here are just a handful of studies or analyses on this:

https://www.carbonbrief.org/factcheck-how-electric-vehicles-help-to-tackle-climate-change/

https://www.carbonbrief.org/factcheck-21-misleading-myths-about-electric-vehicles/

https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/comparative-life-cycle-greenhouse-gas-emissions-of-a-mid-size-bev-and-ice-vehicle

https://www.transportenvironment.org/discover/how-clean-are-electric-cars/

Charging.

I am a renter, like 34% of Americans, 44% of Californians and 63% of residents in Los Angeles. Charging for an hour a week at a public charger is going to be inconvenient. I expect as more locals buy EVs, there will be long waits for chargers, basically ruining one day a week.

Doing the math, paying for a charge up in public will actually cost me more money than refilling my 2004 Prius. So I am not getting the savings always extolled about with regards to EVs.

Supposedly there will be less to break inside and require maintenance, but when I have spoken to EV owners they have told me how expensive damages cost to repair, I guess because they are not yet ubiquitous enough.

I have been wanting an EV for several years, but I don’t make a lot of money. And I don’t have a 220V outlet where I rent where I could plug one in. Newer apartment buildings have parking spots for EV charging. My unit is $2600 a month. Ones with chargers tend to cost more like $4K here. More costs.

Here’s my solution: mandate landlords install 220V outlets in renter parking spots by 2030.

Start with buildings with over 100 units. Give them till 2026.

Then those with over 50 have till 2027.

Those over 25 till 2028

Those over 10 till 2029

And all by 2030.

The IRA gives tax rebates for some of this. States should add more to reduce pushback from landlords.

Yes people want a choice. Yet we are being limited by tax-funded subsidies and incentives. I fully expect to own an electric car at some point -- although I put so few miles on my car so buying a new one is unlikely. My problem with the push to go electric is exactly that is IS being pushed. EVs would be adopted gradually anyway without taxation, subsidies, and compulsion. Pushing them is also a bad idea because it will require more electricity and the USA (like some other countries, especially in Europe) is pushing aside reliable energy sources in favor of highly dilute, intermittent, and unreliable sources. The grid also needs massive upgrades. If we had not all but destroyed nuclear, we would be in a much better position to more quickly adopt EVs --- and electric cookers, and heat pumps... and AI.