Are plug-in hybrids booming or fading, and are they better for the climate?

Plug-in hybrids are still going strong in some markets. Their climate benefits strongly depend on who is buying them.

I often get the question: “I don’t drive many miles; is a plug-in hybrid a better environmental choice for me?”

I’ve written about electric vehicles a lot on this Substack. But I’ve written very little about plug-in hybrids, specifically.

I want to focus on that here: giving a short overview of how plug-in hybrid markets are performing and what role they can play in the transition to cleaner transport.

I’m always surprised by how riled up people get about this topic. There’s a loud crowd who dismiss plug-in hybrids as being the “worst of both worlds”, or a greenwashed version of fully electric. Others think they’re the obvious way to go; that the leap to fully electric is happening too soon. So I have no doubts that the comment section and my inbox will be lively.

How popular are plug-in hybrids?

First, to make sure we’re all on the same page.

Fully battery-electric cars (BEVs) — as the name would suggest — drive exclusively on electricity. No gasoline or combustion engine.

Plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) have an electric motor, battery (which is charged by plugging it in), and combustion engine. They have a smaller battery: they typically go around 20 to 40 miles on a single charge, compared to 250+ miles in BEVs. When the electric power runs out, they switch to running on petrol, just like a typical gasoline car.

Don’t confuse PHEVs with “hybrids”. These cannot be charged by plugging them in, have a really small battery, and are basically gasoline cars with slightly higher efficiency.

How many people are buying plug-in hybrids compared to fully-electric? In the chart below you can see sales of new PHEVs and BEVs across a range of markets since 2010. This data comes from the International Energy Agency, and you can explore the data for other countries in this interactive chart.

Both segments have grown a lot in the last decade, but with a varied pattern across different countries. In Norway, plug-in hybrid sales have effectively died, as BEVs now dominate. Plug-in hybrids are also growing much more slowly than BEVs in the United States and the EU. But in China, plug-in hybrids are still going strong.

At the global level, around two BEVs are sold for every plug-in hybrid. If you look at the annual growth rate of PHEV sales over the last five years, they’ve been growing slightly faster than fully-electric cars, and much faster than petrol ones (which are actually shrinking).

So plug-in hybrids are not out-of-the-race.

China is making longer-range plug-in hybrids

The average plug-in hybrid car in Europe and the US can go around 45 to 60 kilometres on a single charge. Until the early 2020s, this was the average for the world, too.

But in the last few years, China has been pushing this range much higher. You can see this in the chart below, which comes from a great article by Colin McKerracher, Head of Transport at BloombergNEF.

China’s average is now well above 80 kilometres, and closing in on 100. This has pushed the global average up to 80 kilometres too.

But it’s not just “standard” PHEVs where manufacturers are pushing the limits. Companies are launching models with range extenders, which can reach well over 100 kilometres (see the chart below). From an environmental perspective – as I’ll come on to soon – this is a good thing because drivers will spend more time in electric mode, and less in petrol mode.

The cost of plug-in hybrids compared to fully electric and petrol

One of the reasons why plug-in hybrids are still going strong in China is that their price has fallen dramatically in the last 5 years. The chart below comes from BloombergNEF again.

They’re still not as cheap as battery-electric. The fact that plug-in hybrids cost slightly more than fully battery-electrics might surprise some people, because there is the assumption that PHEVs are a useful “bridge” for people that can’t afford to go fully-electric.

Plug-in hybrids are also not much cheaper than BEVs in the UK. The cheapest PHEVs are in the range of £25,000 to £35,000, which is now similar to fully battery-electrics. In fact, there are quite a few BEVs that are even cheaper than this, such as the Dacia Spring or Citroen e-C3.

The running costs of BEVs will be cheaper than PHEVs. Both are cheaper to run than petrol.

What’s the carbon footprint of plug-in hybrids?

Do plug-in hybrids emit much less than a petrol car? And are there any scenarios when they’re actually better than BEVs?

On the first point, yes: since plug-in hybrids run on electricity at least some of the time, they emit less carbon over their lifetime than a standard petrol car. How much less depends on two factors: how often it’s running on electricity and how clean the grid is.

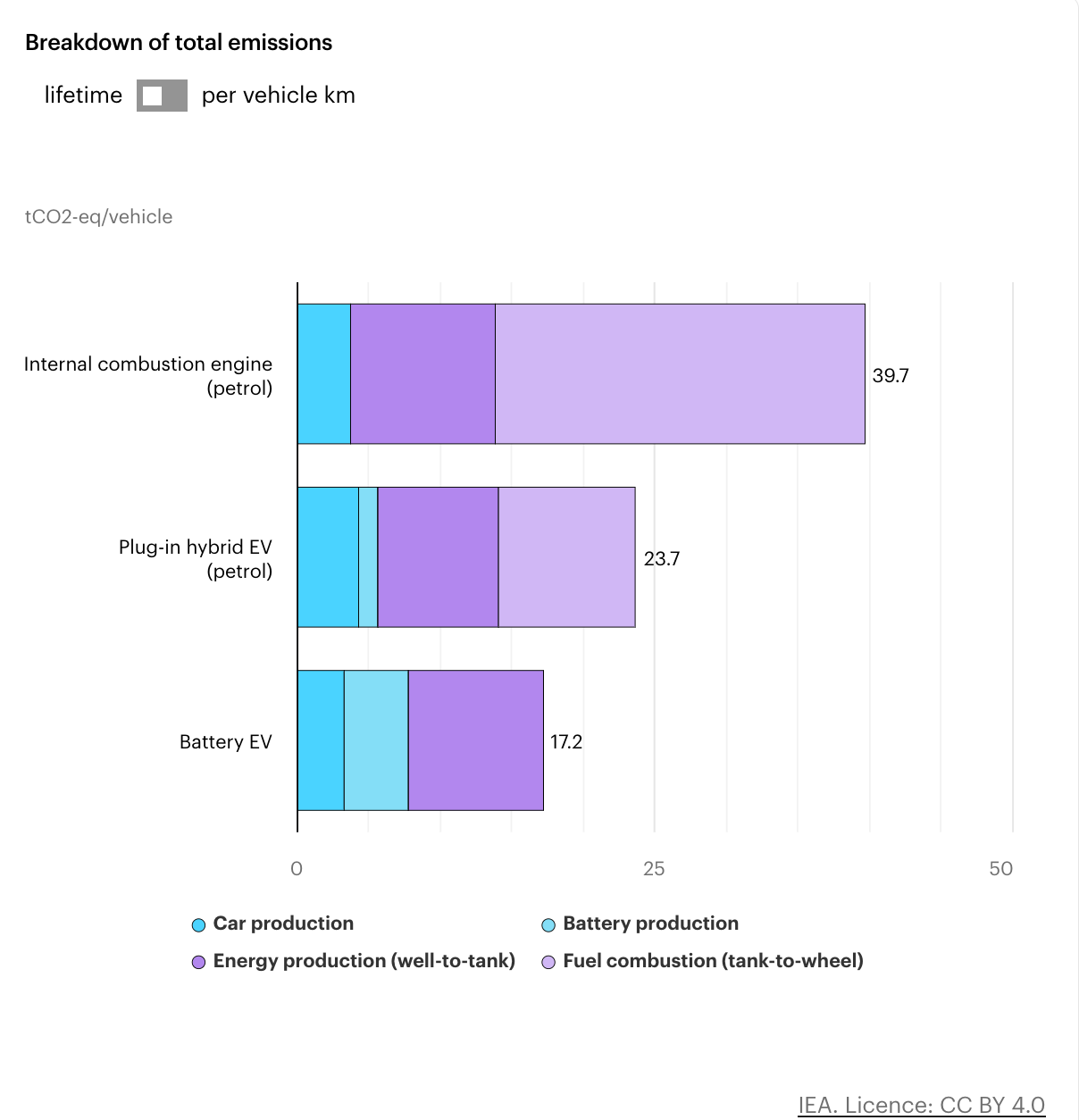

The International Energy Agency has a useful tool for comparing the life-cycle emissions of petrol, plug-in hybrid, and fully electric cars under various scenarios. You can change many inputs, including the daily mileage, the electricity mix, and the share of the time drivers spend in “electric mode.”

You really have to take it to the extreme to get an outcome where plug-in hybrids are worse than petrol. Daily driving distance needs to be very low (less than 5 kilometres), and the electricity grid needs to run almost exclusively on coal. So, it’s mathematically possible but uncommon in the real world. For a typical driver in the UK or the US, the savings are large: a third to 50% less.

Is a plug-in hybrid ever lower-carbon than a fully battery-electric?

The rationale is that the carbon footprint of manufacturing a BEV is higher than a PHEV because it has a bigger battery. If you always run the PHEV on electricity, then the carbon footprint of driving the two cars should be the same. Hence the lifetime footprint of PHEVs can be lower.

The first part is true: the chart below shows the average carbon footprint of manufacturing a petrol, PEV and BEV car. The BEV emits around two tonnes more CO2.

The second part can also be true. If you drive very short distances and charge daily so that you never run on petrol, then the emissions from driving should be similar (not exactly the same because it will depend on the efficiency and comparative weights of the cars).

But this is not how most drivers operate. Many standards have vastly underestimated the fuel consumption, efficiency rating, and carbon emissions of PHEVs because they are too optimistic about how often drivers recharge and run on electric power.

I did a quick review to find estimates of the share of miles that people cover on electric mode in the “real world.” The tables below summarize the data for private and company cars.1

For private cars, it’s around half of the time, but with even lower percentages in some markets. For company cars, it’s far worse — just 11% to 24% — because the drivers aren’t the ones paying for the fuel.

This is far lower than standards such as the Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicle Test Procedure (WLTP) and US EPA labelling standards assume.

Take the travelling distance and behaviour of the average driver, and BEVs emit significantly less over their lifetime. The chart below is a good approximation for a driver in the UK.

So, if you’re incredibly conscientious about charging frequently and never drive distances further than the typical 50-kilometre range of PHEVs then you could make the case that it’s the best climate-friendly car for you. For most people, it’s not as good as a BEV.

What are the other pros and cons of plug-in hybrids?

Is the popularity of plug-in hybrids a “good” thing for the climate or not?

It really depends on who is buying them and what their preferred alternative would be.

If they would have gone fully electric but fell back on a PHEV as a “safe” option, it would be a negative outcome for climate. If they had rejected the option of a BEV and would opt for another petrol car, then it’s a positive climate outcome.

I haven’t seen good data on the attitudes and preferences of PHEV buyers to know how many fall into each category.

Beyond climate, and there any benefits or cons of plug-in hybrids compared to all-electric?

They do have a smaller battery and, therefore, a smaller mining footprint. I’m not concerned about this from a “we’re going to run out of minerals” perspective (which Toyota likes to claim). I also don’t think the mining footprint for clean energy is going to be huge and unsustainable; it’s going to be lower than using fossil fuels. But using materials efficiently is simply a good thing, so that’s a fair argument.

The argument that “fully electric vehicles will put unsustainable strain on the grid, so smaller PHEVs are better” is a poor one. I actually think the opposite is true: with smart vehicle-to-grid systems, BEVs could play a role in balancing out the grid. Most countries will need to add significant battery storage to the grid anyway; why not utilise the cars sitting idle in peoples’ driveways?

One final downside of opting for a plug-in hybrid is that your purchase plays a smaller role in driving cost reductions for all-electric cars. The big game-changer for electric cars has been the plummeting costs of batteries. Without this drop, the transport transition would not happen. This decline has been driven by incremental gains as production has scaled up (the so-called “learning curve”). By buying an electric car earlier (often when they’re more expensive), you’re pushing down the cost for others. The same is probably true for the other elements of electric cars that are different from traditional petrol designs.

Buying a PHEV will still help the cost curve to some extent, but not as much as a BEV. If the end goal is to electrify — with PHEVs being a bridge to that — then optimising the production of fully electric cars is essential to getting us there.

These figures are sourced from the following reports:

Hao, X., Yuan, Y., Wang, H., & Sun, Y. (2021). Actual electricity utility factor of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles in typical chinese cities considering charging pattern heterogeneity. World Electric Vehicle Journal.

As always a great post and I cannot argue with the facts as laid out. But (and the following is valid, if at all, only in the USA, where I live) I think you leave out the range anxiety issue. Data point of 1: I used to own two ICE vehicles. I sold one and replaced it with a BEV. On my first long trip I ran into broken chargers, chargers that would not read my card, and wildly fluctuating remaining-range estimates on my dashboard (insert here obligatory "Should have gotten a Tesla!" comment). Unsettling. I kept the BEV but replaced ICE #2 with a PHEV. I have had the PHEV (Prius Prime) for half a year. I have taken TWO long trips in it, and indeed then it runs on gasoline (~50 MPG). For 100% of the rest of the time (and I do mean 100%) I charge it. Range anxiety gone. None of what I have written does anything to change the facts you have laid out, but I wanted to highlight the motivation (at least for me) for buying one, that was not emphasized in your post, which stressed mostly the supply side, not the demand side. Purists will (correctly!) argue that we should be 100% BEV (or FCEV). I agree. But the best can be the enemy of the good. I have persuaded 3 people I know to swap an ICE for a PHEV, 3 people who would not have bought a BEV. Was this not a good thing to do? Would a vegan dissuade an omnivore from becoming a vegetarian, because being a vegan is the best outcome?

The main advantage of PHEV is their flexibility for when reliable charging infrastructure is not available but people still want some cost savings from an electric drive train. This is the very scenario our household is facing. Living in an older building, it may take several years before we have individual charging available in our parking spots, so a BEV is basically out of the question. There is also a general lack of charging available in the areas surrounding our city here in eastern Ontario, as much of the territory is quite rustic. A PHEV hedges that there may be better charging available in the lifespan of the car, but still operates for those unavoidable long range drives. Much much better charging infrastructure and ranges (at least 600km) are needed to make BEVs viable in geographicallly dispersed, low density areas.