Artificial intelligence could dramatically improve weather forecasting

An AI-based model outperformed every other in forecasting the Indian monsoon this year. This helped millions of farmers.

One of the most promising prospects for artificial intelligence (AI) is in weather forecasting.

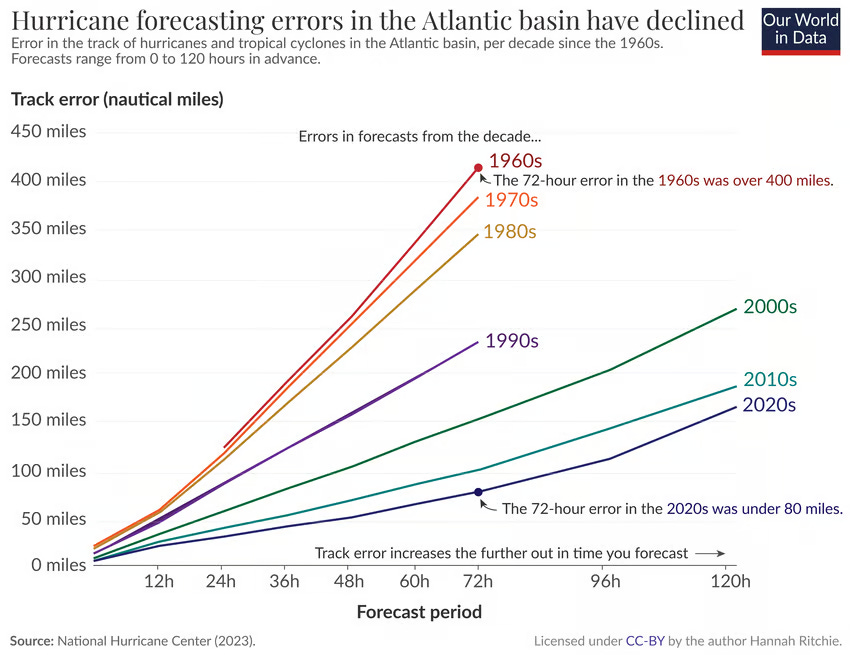

Accurate weather forecasts are something that many of us now just take for granted. Whenever I say this, people often complain about the inaccuracy of weather forecasts. But look at the data (I previously wrote about it) and you’ll find that they have improved a lot over the last 50 years. See the improvement in hurricane forecasts in the chart below.

But, of course, there is still room to do better, and importantly, make this quality of forecast available to everyone. Seven-day forecasts in rich countries can be more accurate than a one-day forecast in some low-income ones.1

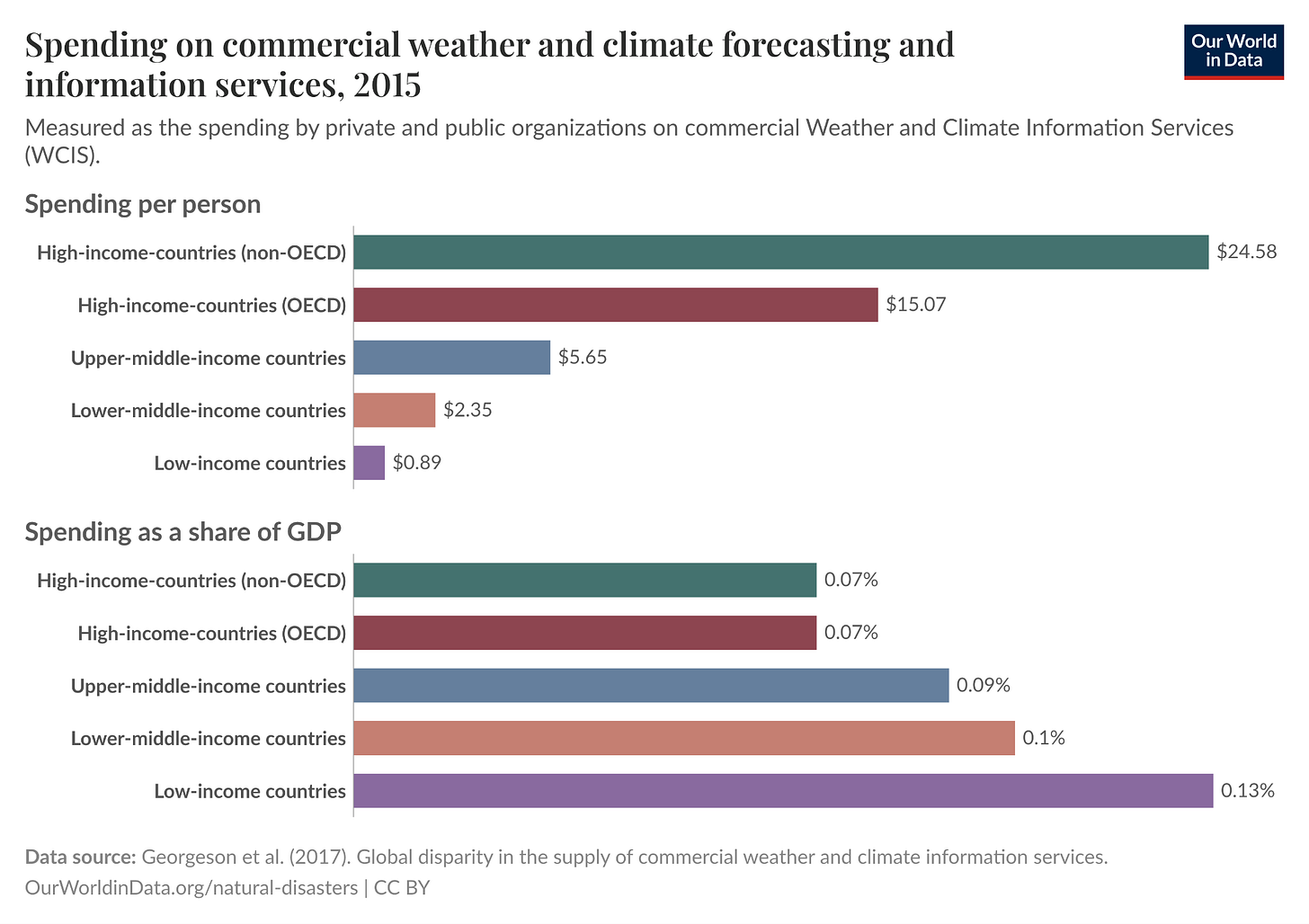

A key barrier for low-income countries is a lack of funds. In the chart below, you can see that the amount spent per person on forecasting in low-income countries is a fraction of that in high-income countries, yet as a percentage of GDP, they actually spend more.2

Weather forecasts are important to almost everyone, but they can make a huge difference to farmers (which is the majority in low-income countries) as they guide them on when and what to plant. A good forecast could be the difference between a great harvest and none at all.

This is where AI could really change things. It has the potential to not only improve the accuracy of forecasts but also to run them more quickly and efficiently. That then makes them better and cheaper.

An AI-powered model forecasted the Indian monsoon better than any other

The potential for AI to improve weather forecasting and climate modelling (which also takes a long time and uses a lot of energy) has been known for several years now.3 AI models have been tested for one- and two-week forecasts with promising results.4 Scientists will often need to wait weeks for a complex, high-resolution climate model to run; AI might be able to do this hundreds, if not thousands, of times faster.

But a huge trial in India this year has taken a huge step forward. The Indian Ministry of Agriculture partnered with teams of scientists from the Human-Centred Weather Forecasts Initiative, the University of Chicago, California, Berkeley, Bombay, Bangalore, and others.

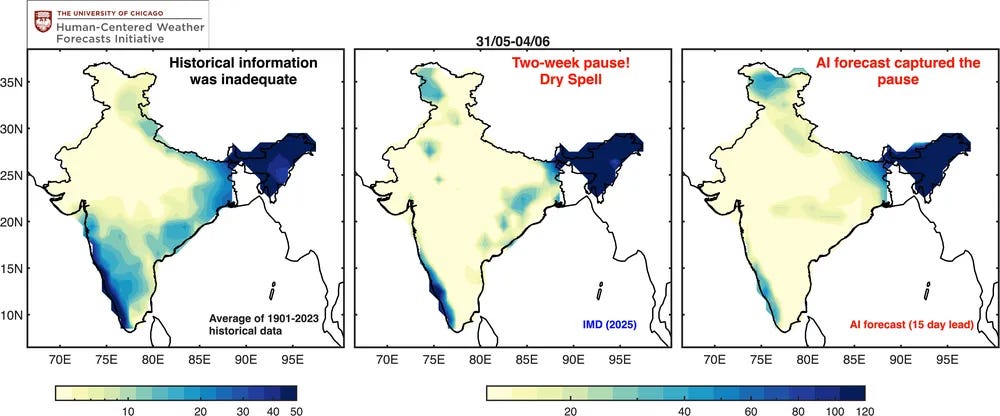

They sent weekly AI-powered forecasts about the monsoon to 38 million farmers across 13 states in India. These AI forecasts predicted changes in the monsoon that all other ones missed. The forecasts of the timing of the monsoon were sent up to four weeks in advance of its arrival; conventional physics-based modelling usually can’t do it more than five days in advance.

This year’s monsoon was a weird one. It hit Southern India in early June (which the AI model predicted), but then stopped temporarily for 20 days. No conventional model predicted this stall, but the AI-based one did.

Again, this information can make a huge difference to farmers. Knowing that the monsoon would stall for three weeks meant that farmers could delay their planting to take advantage of the rain or choose to plant a different crop. In a self-reported survey, around one-quarter of the 38 million farmers adjusted their plans in response to the forecast. I would expect that as these models and forecast messages became more trusted, this share would increase.

The onset and progression of monsoons are extremely hard to forecast, but even small improvements can make a huge difference. Michael Kremer, the Nobel Laureate economist and co-director of the Human-Centred Weather Forecasts Initiative, estimates that they easily pay back: “Disseminating AI weather forecasts has an incredibly high return on investment, likely generating more than $100 for farmers for each dollar invested by the government.”

These return-on-investment calculations are often quite hard to verify — especially with a limited number of trials to draw upon — but I can easily believe these numbers to be true. The rollout of digital technologies can often be cheap, and in this case, the cost of getting it right or wrong in terms of agricultural returns is high. Spreading the cost of an AI model across tens or even hundreds of millions of farmers means the per-farmer cost is extremely small.

This is one of the AI applications I’m most excited about at the moment. It’s not some prediction of what AI-based models might be able to do in the future; we already know that the models today could be a huge improvement. They could deliver low-cost, more accurate forecasts for farmers, and could forecast disaster events even further in advance. That will save and improve lives, especially in a changing climate.

Linsenmeier, Manuel & Shrader, Jeffrey G., 2023. “Global inequalities in weather forecasts,” SocArXiv 7e2jf, Center for Open Science.

This data is around a decade old now, but I expect the gap between low- and high-income countries has not changed much (even if the absolute amount has).

Georgeson, L., Maslin, M., & Poessinouw, M. (2017). Global disparity in the supply of commercial weather and climate information services. Science Advances, 3(5), e1602632.

Wong, C. (2024). How AI is improving climate forecasts. Nature, 628(8009), 710-712.

Lam, R., Sanchez-Gonzalez, A., Willson, M., Wirnsberger, P., Fortunato, M., Alet, F., ... & Battaglia, P. (2023). Learning skillful medium-range global weather forecasting. Science, 382(6677), 1416-1421.

Weather forecasting is also increasingly important to managing electricity grids and anticipating near term generation (and storage) requirements. As more renewable energy is added it will become even more significant.

Google AI did a great job of tracking Hurricane Melissa which is currently wacking Jamaica after following a pretty erratic track. Those extra days warning make all the difference when you are on the ground. Unfortunately, it's a monster.