How many people died in disasters in 2024?

Less than last year since there were very few catastrophic earthquakes.

This is the second article in a three-part series summarising food production, disaster deaths and wildfire extent in 2024. You can find my article on food production here.

How many people died from disasters in 2024? Here, I’m talking about meteorological and geological disasters — events like floods, hurricanes, wildfires, and earthquakes.1

My instinct going into this was “less than last year” and close to an “average year” because there weren’t many major earthquakes. From looking at this data before, years with large death tolls nearly always have catastrophic earthquake or tsunami events.

Having seen the results, this turns out to be a reasonable summary.

For this analysis, I’ll be relying on data from EM-DAT, the world’s largest open international disaster database. It provides extensive line-by-line detail on recorded disaster events, which you can download and explore here.

Warning: this data is not perfect, in particular for temperature-related deaths and drought. I’ll make some adjustments for this soon, and for those interested, I’ll include a section at the end explaining some of these issues in more detail.

Let’s get into it.

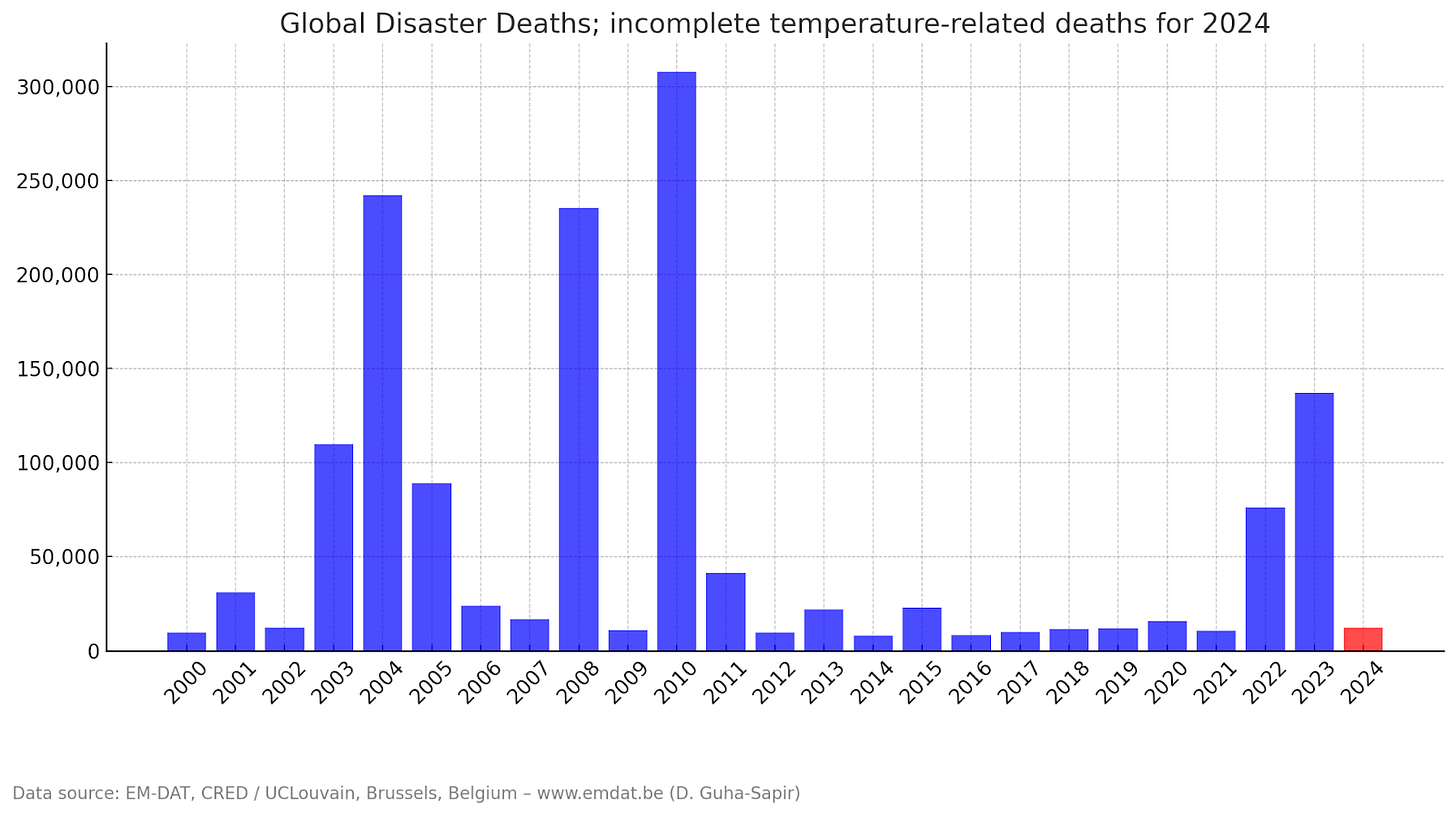

Below you can see the number of global disaster deaths from 2000 to 2024.2

2024 looks pretty low, especially compared to the previous two years, and certainly compared to many years in the first decade of the 2000s.

One problem with this raw data, though, is that deaths from extreme temperatures are incomplete. Estimating deaths from heatwaves and cold snaps is much harder than those from events like earthquakes or wildfires. People might imagine that most deaths from temperature are people dying from heatstroke or hypothermia. But most are premature deaths from other conditions, like cardiovascular, respiratory or kidney disease, or a stroke. Estimating these figures takes time, and researchers rely on methods such as “excess deaths” (where they look at how many more deaths happened over a summer or winter period than you would expect in a “normal” year). I described some of these methods in detail in a series on heat deaths for Our World in Data.

Anyway, these deaths take time to estimate, and they’re not yet available for 2024 (and probably won’t be until later in the year). So I’m going to remove temperature-related deaths from all years, not because I’m “cherrypicking” in some way, but because 2024 is artificially low compared to previous years.

So here’s that same time-series without temperature deaths included.

2024 was still a relatively “low” year. The current estimate (without temperature) was 9,500 deaths. That’s similar to most years in the 2010s — which averaged 13,700 deaths — and much lower than the average for the first decade of the 2000s, which was around 93,000.

As I mentioned earlier, what explains most of this multi-decade pattern are earthquakes. Nearly every “big” year had one if not multiple, huge quakes.

In the chart below I’ve shown the earthquake deaths in purple, and the remainder in brown. Nearly all of the stand-out years are completely dominated by purple: the Boxing Day Tsunami in 2004; the Kashmir earthquake in Pakistan in 2005; the Port-au-Prince quake in Haiti in 2010; and the devastating earthquakes in Turkey last year.

The one exception is 2008, which still had a lot of earthquake fatalities (around 90,000 died in the Sichuan earthquake in China) but also saw almost 140,000 deaths when Cyclone Nargis struck Myanmar.

Humans have become much better at protecting people (property is another matter) in disasters like floods, wildfires, and hurricanes. But we’re still extremely vulnerable to earthquakes.

Finally, here’s a further breakdown of disaster deaths by type.

If there weren’t many major earthquakes in 2024, what were the events that caused the most fatalities?

Floods: Heavy rainfall and extreme flooding in Chad killed more than 500. There were also flooding events killing several hundred people in other parts of Africa, and across South Asia including Niger, Nigeria, Pakistan and Afghanistan. In Europe, devastating floods in Spain killed more than 200.

Wildfires: South America experienced severe wildfires this year. While most events killed very few people (at least, directly), the fires in Chile killed almost 400.

Storms: There were five cyclone events that killed more than 100 people, in Myanmar, Vietnam, the United States, the Philippines, and Mozambique.

Landslides: Landslide events in Ethiopia, Uganda and the Philippines all killed more than 100.

Challenges and issues with records of disaster deaths (optional)

These international disaster databases are incredibly detailed. But even EM-DAT makes clear that its data has limitations, in its documentation.

I previously wrote about many of these limitations on Our World in Data if you want to dig in deeper.

But here’s a summary of some of the key caveats to the data above. First, EM-DAT doesn’t release its official report for 2024 until March.3 That means there might be some refinements to the numbers before then. But I don’t expect major differences that would change the main headline; if deaths are added, I would expect them to be from temperature or drought.

As I mentioned earlier, there’s always a lag in temperature-related deaths so the 2024 data is certainly incomplete. But that’s not the only issue I have with the recording of temperature deaths, for all years not just 2024:

Not every region does the more complex analyses to estimate these premature deaths, which means that it’s mostly just Europe that’s included.4 I find it hard to believe that no one (or only a handful) dies in South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, or South America from heatwaves or cold conditions.

The focus tends to be on heatwave events, but we know from more in-depth academic research, that many also die prematurely from colder temperatures (in fact, it’s many more). These are often not included.

In-depth studies find far more temperature-related deaths than are included in these databases.

In other words, the data for every year is incomplete and not consistent over time. That’s why I prefer to look at EM-DAT data excluding temperature deaths, and then focus on the more detailed literature on heat deaths to understand how they are changing.

The other category of disaster that’s much less certain is drought. There is a more complex chain needed to attribute a death to drought — which is often the result of hunger and malnutrition — than to, say, an earthquake. See the UNDRR’s Special Report on Drought for more details.

It should go without saying that we also care about people losing their homes, being displaced, and infrastructure being destroyed. None of this is captured in death metrics.

Unfortunately data on reconstruction costs and damages is often incomplete, and many events in 2024 will not yet have a monetary damage assigned to them.

On Our World in Data, we have data from EM-DAT stretching back as far as 1900. However, EM-DAT note that pre-2000 data is often incomplete, and I would expect that deaths in the 20th century are significantly underestimated.

I'm assuming it'll be March because of when the 2023 report was released last year.

Over half of heat events in EM-DAT were reported across only 9 countries: Japan, India, Pakistan, the United States, France, Belgium, the United Kingdom, Spain, and Germany.

David McCauley and Daniel Stephen Swords :

Stop being lazy.

Do your own research and if you want to share [ like Hannah has done] then fine !

Can you break out numbers for climate-related or climate-induced disasters, using the best available attribution science?