Net-zero: it’s not just where you end up, but how you get there that matters

Delaying emissions cuts makes climate change worse, even if countries reach net-zero in 2050.

Many countries have set targets to reach ‘net-zero’ emissions. The UK – alongside others – has pledged to achieve this by 2050.

That’s almost three decades away, which means it needs a long-term plan to get there. The problem is that long-term plans don’t sync with four-year election cycles (or if you’re in the UK, the even shorter turnover of Prime Ministers – we’re on our 4th since 2019).1

Leaders today can have weak climate policies with the continued promise that their countries will still reach net-zero by 2050.

In the last few weeks, Rishi Sunak, the UK’s Prime Minister has rolled back a number of near-term climate policies while denying that this puts the 2050 target in danger.

Last week, I spoke with Tim Harford on BBC More or Less about the problems with delaying emissions cuts. There are a few.

The most obvious is that it makes emissions reductions incredibly steep later. If you have high emissions until 2040, then you’re going to need a decade of extremely rapid cuts. People are pretty resistant to abrupt change, so expect a lot of pushback. It’s going to seem technically impossible and politically unpopular. Don’t be surprised if the 2050 target gets delayed even further.

But there is another problem. What’s important for climate change is not just where every country ends up, but the path they take to get there. It’s cumulative emissions that determine global temperature rise. How much countries emit on their path to net-zero really matters.

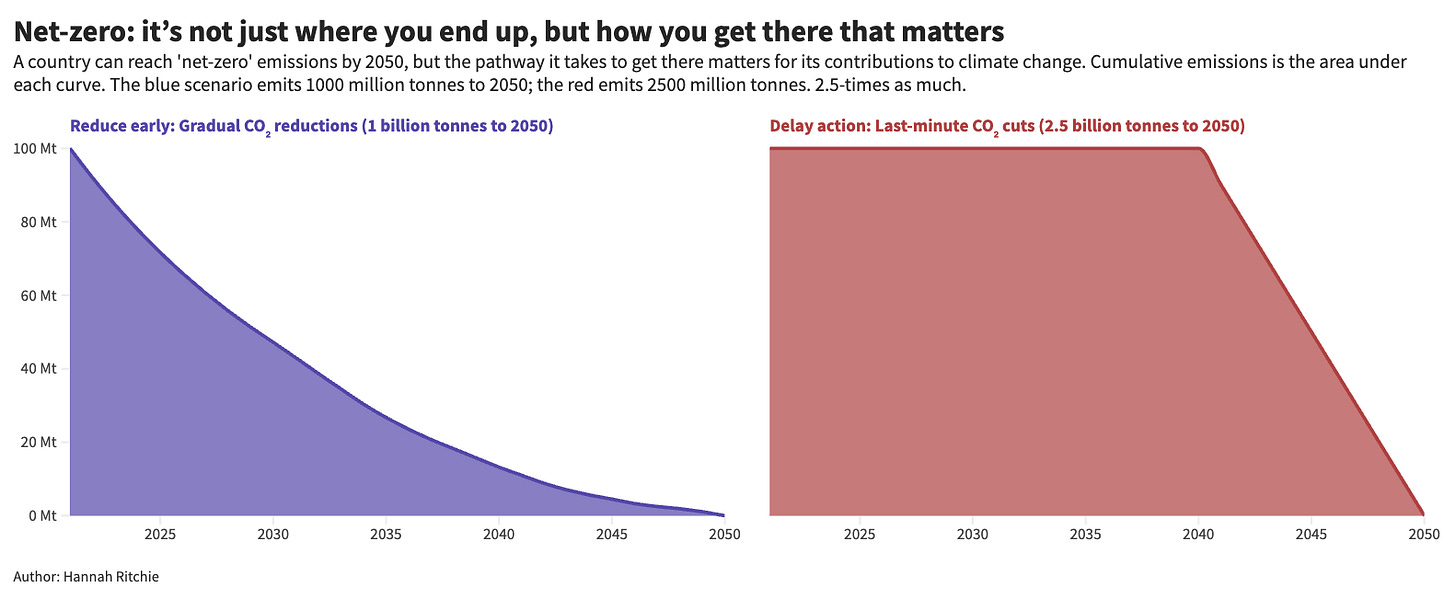

I’ve done a quick sketch below to show this. It plots annual emissions on the y-axis, and time along the x-axis. In the blue scenario, a country gradually reduces its emissions, reaching zero in 2050. In red, a country has high emissions until 2040 then it rapidly reduces to zero.

The area under the curve is a country’s cumulative emissions, and how much it contributes to climate change. When we reduce emissions earlier – like the blue scenario – we emit much less overall.

We can see this from a simple example. The two curves below start and end at the same point: emissions are 100 million tonnes in 2021 and reach ‘net-zero’ in 2050.

But in the first scenario, emissions are reduced gradually over the 30-year period. In the second, emissions remain high until 2040 and are then cut steeply.

Both can celebrate that they’ve reached their ‘net-zero’ target in 2050. But their contribution to climate change along the way is vastly different. In the first scenario, 1 billion tonnes are emitted over 30 years. In the second, it’s 2.5 billion tonnes. 2.5-times as much.

Setting a net-zero target is great – the earlier the better. But there’s a risk that countries fixate too much on the end goal, and don’t care about how they get there. If every country delays emissions cuts, it not only makes the final target less attainable, it makes climate change a lot worse in the interim.

And there is a final problem with the ‘last-minute rush’ approach. It’s a free-rider problem.

You could argue that waiting until 2040 makes it much cheaper to reduce emissions. At least in terms of up-front costs (which is what leaders in short political cycles care about). Over the medium- to long-term, it’s a different story. These investments pay back through reduced fuel costs and efficiency gains such that acting early actually saves money.2

If the price of low-carbon technologies continues to fall, the UK could deploy them much more cheaply in 2040 than they can today. Electric vehicles could be much cheaper than petrol and diesel. Heat pumps could be half the cost of gas boilers. Solar and wind costs could continue to tumble.

But these cost reductions only happen through early investment and deployment. The more solar panels, wind turbines, and electric cars the world buys, the cheaper they get. These technologies follow ‘learning curves’. The role of rich countries is to invest in these technologies early when they’re more expensive, to drive down costs for the rest of the world. Now, the UK can choose who it wants to be in this scenario. Does it want to be a country that steps up and contributes, or does it want to be a free-rider that waits for others to make these technologies cheap?

People often argue that the UK is ‘too small’ to make a dent in the world’s carbon emissions. It only emits 1% [if you’re interested, I explained why this is a faulty argument here]. But this ignores the role that the UK can play in building low-carbon development pathways for the rest of the world.

This is not even about the UK ‘sacrificing’ its economy for climate change. As I’ve shown before, economic growth and emissions reductions are not incompatible. Moving early on these technologies also represents an opportunity. If electric cars are going to be the default transport mode for the next 50 to 100 years, then there is the opportunity to be a leader in that sector. Same for heat pumps, or any other technology. Wait too long and you’ve missed the boat.

Theresa May was in office until the end of July 2019.

Boris Johnson was then in office from 2019 to 2022.

Liz Truss lasted less than 2 months from early September to the end of October 2022.

Rishi Sunak has been the leader since.

Way, R., Ives, M. C., Mealy, P., & Farmer, J. D. (2022). Empirically grounded technology forecasts and the energy transition. Joule, 6(9), 2057-2082.

https://www.cell.com/joule/fulltext/S2542-4351(22)00410-X

It is important to note that making solar, wind and batteries requires enormous amounts of energy which is currently mostly provided by burning fossil fuels. As a result rapid expansion of these technologies is actually accelerated greenhouse gas emissions. This explains why burning of fossil fuels is now at record levels ever despite record expansion of solar, wind and batteries.

Expanding nuclear might be slower because of the time taken to build these plants, but it is not energy intensive and so will not cause a big spike in fossil fuel use. It will should result in much faster declines in greenhouse gas emissions. Historically, expansion of nuclear power has been by far the fastest way to reduce emissions associated with electricity production.

https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/5lerrj0g1n5tvl88vklbb/Science-2016-Cao-et-al.pdf?rlkey=9avyiws5vj9v36q1fqhwh2k28&dl=0

The article raises a key aspect of net zero, so thanks for that. Slight reservation though regarding one of your last sentences saying that "economic growth and emissions reductions are not incompatible". To be accurate, it should read "economic growth and emissions reductions are not incompatible although insufficient to reach a goal that is good enough to meet the Paris Agreements". There is a relatively long economic literature showing the limits of decoupling, which is often temporary, not caused by systemic changes but rather by external causes (hence its temporary aspect), or no where near fast/drastic enough in order to respect goals sufficient to maintain a liveable planet.

For example Hubacek et al (2021) conclude that these countries (the countries of the economic North you talk about in your OWID article) “cannot serve as role models for the rest of the world” given that their decoupling “was only achieved at very high levels of per capita emissions”.

All in all, the following article better presents why and how the examples we have of decoupling are not enough (or not related to genuine Green Growth) than I will ever do, and is extremely thorough and methodical, so I encourage you to read it:

https://timotheeparrique.com/decoupling-in-the-ipcc-ar6-wgiii/