Do US states with more renewable energy have more expensive electricity?

Despite California being the poster child of high prices, the data suggests no.

Last week I published two interactive slide-decks on state-by-state electricity data in the United States: one looking at electricity sources, and the other looking at prices and bills.

They were more popular than I expected, which makes me question why agencies like the US EIA do not make this information more digestible for users. They do, after all, do the invaluable work of gathering and publishing the data— why not go to the effort of making it understandable so that people use it properly? I get that this takes a bit of resource, but it’s not much: if I can do it on a Sunday afternoon, I’m sure they could collectively pull it off.

Anyway, several people asked me to combine the two: to look at how a state’s electricity mix affects consumer prices. Do renewables make them more expensive? Does gas make them cheap?

So here, we’ll briefly look at the relationships between the two.

As a warning: if you’re expecting to see a clear correlation — that all states with lots of [solar / wind / nuclear / gas] have much [cheaper / more expensive] electricity — then I’m afraid you’ll be disappointed.

For every state that has lots of [Source X] that has cheap electricity, we can point to another that has expensive electricity. There are so many elements that come into power pricing — not just the fuels and power plants themselves, but the transmission and distribution, capacity payments, the market design, taxes, grid fees etc. These factors can often matter a lot more in state-to-state comparisons. This is also true when comparing different countries, which is why I’m often cautious about doing so. What can be useful is to look at changes in prices for an individual state or country over time. I’ll briefly look at that later, too.

Disclaimer: I’m not an expert on state-by-state power markets and regulations. I don’t know the nuances of the structures in California versus Iowa versus Alaska. My aim here is to present the latest data; not to provide the ultimate overview of US electricity markets (and how to fix them).

Do solar and wind power make residential electricity more expensive?

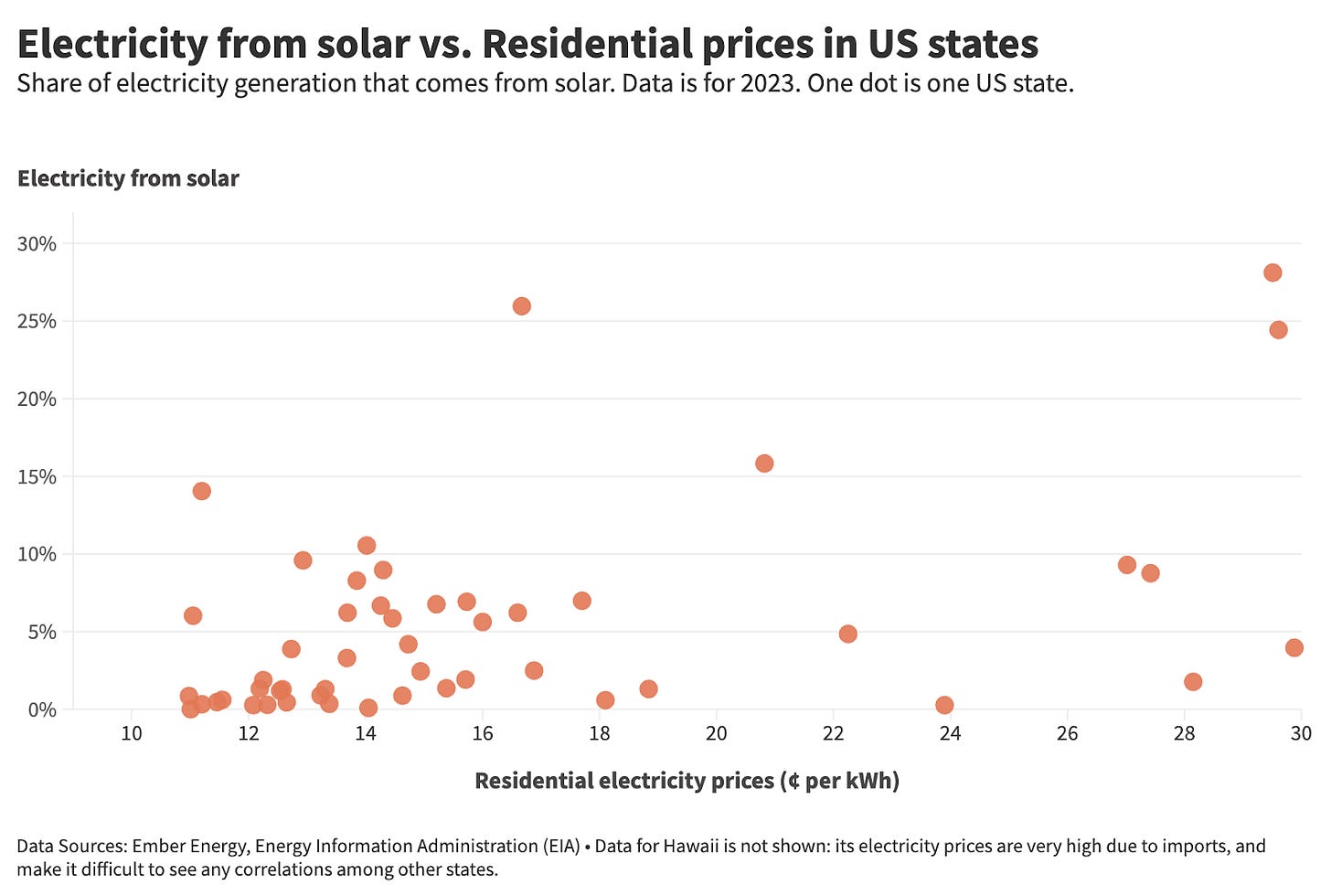

In short, no. The chart below plots the share of electricity generation coming from solar and wind on the y-axis and residential electricity prices in 2023 on the x-axis.1

Some of you might be expecting California — the American poster child for renewables — to be on top here. But there are a bunch of other states with a higher share of solar and wind (mostly because of wind). You see these states clustered in the top left. Iowa, South Dakota, Kansas, and New Mexico all have a high share coming from solar and wind and cheap prices. The argument that solar and wind automatically equals expensive electricity — which people often make by pointing to California — is not supported by this data.

On the right-hand side, we do find states like California and Massachusetts with moderate amounts of solar and wind that do have expensive power. But, equally, we find states with expensive electricity like Connecticut and New Hampshire with almost no solar and wind.

In other words, having lots of solar and wind doesn’t guarantee that you have cheaper or more expensive power than your neighbours. Nor does the absence of solar and wind guarantee that your power will be cheap.

Note: all of these charts have an interactive version that I’ll link to, so you can explore where different states are.

Above, we’ve been looking at residential prices, rather than costs for industry or commercial sectors. Residential and industry prices can be quite different. Countries and states often charge lower rates for industry. This is true in the US too. But there’s a very strong correlation between residential and industry prices: states with higher residential prices also have higher industry rates. And when I compared solar and wind shares with industrial prices, the same pattern emerged (explore the data here). The story is consistent regardless of what type of consumer we’re looking at.

Do solar or wind make residential electricity more expensive?

What if we look at solar and wind individually?

Below you can find the same chart, but with the share of electricity from solar only, on the y-axis.

It’s here that California stands out on the right. It was the state with the largest share coming from solar in 2023. It was also one of the states with the most expensive electricity.

Maybe, then, solar does automatically push up prices? Nevada - shown in the middle - seems to dispute this. It has almost the same share coming from solar as California, but its electricity is about half the price.

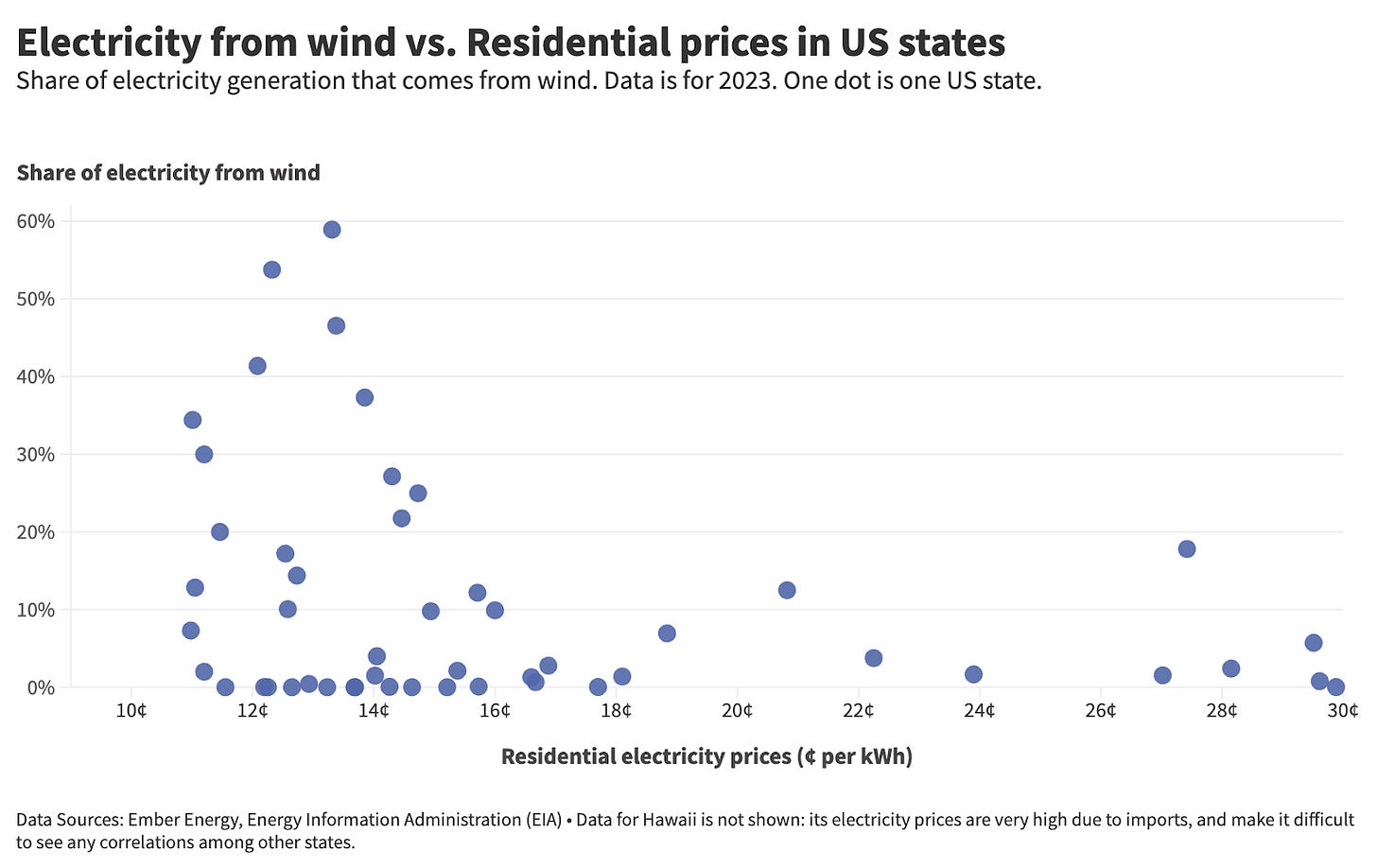

What about wind? Look at the chart below.

There are lots of states with lots of wind, and low electricity prices.

What about gas?

The US is blessed with cheap gas resources. So do states with lots of gas have cheap electricity?

See the chart below.

Again, there’s basically no correlation. There are plenty of states with cheap electricity that get most of their electricity from gas. Equally, some of the cheapest states have almost no gas. And there are some states with plenty of gas that are among the most expensive.

And nuclear?

You guessed it. There’s not a clear relationship from the state-by-state data.

You can have cheap electricity with lots of nuclear. You can also have cheap electricity with none.

Looking at electricity prices over time

I’ll say it again: you can’t learn a lot about the impacts of different energy sources on prices by looking at prices across states (at least not right now). Perhaps the biggest takeaway is that you can have lots of solar and wind without having expensive electricity. The same is true when looking at differences across countries.

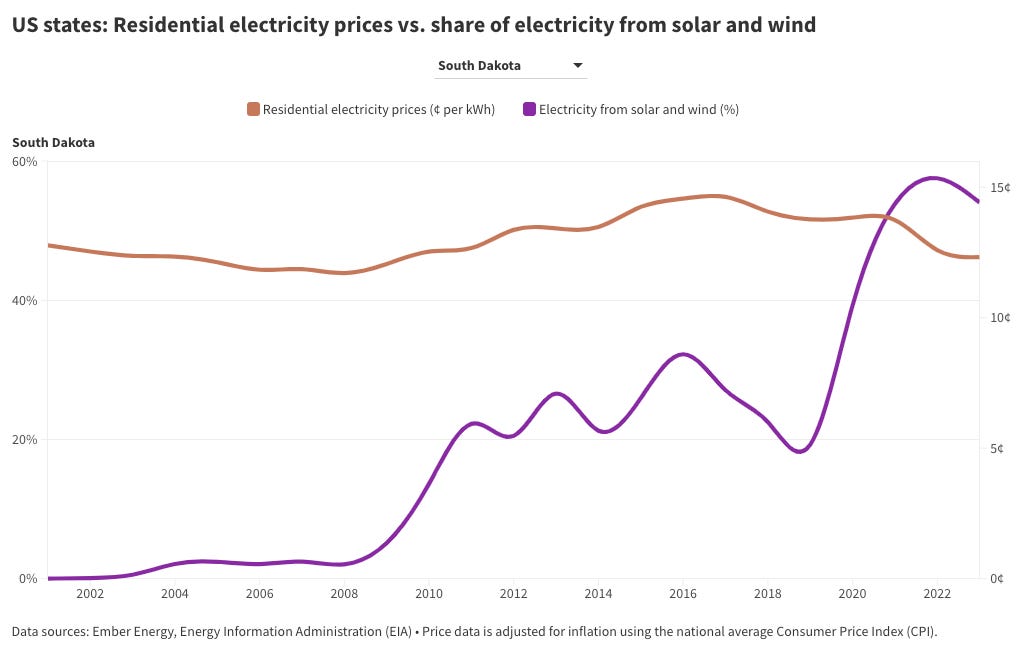

But, it can be useful to look at changes in prices for a given state over time. Of course, there are a bunch of factors that can be changing within the state’s pricing system that have nothing to do with decarbonisation. But shifting towards low-carbon sources is arguably the biggest.

The scariest chart for a renewables rollout is the one below. Solar production in California has increased, but prices have increased by 50%, too.2 That’s the classic “renewables push up prices” narrative that we often hear about.

It’s worth noting that while prices per kilowatt-hour are high, the average Californian’s monthly bill is comparable to many other states, in part due to efficiency measures. And, its electricity was already pretty expensive — at more than 20 cents per kWh — in the early 2000s, before it started rolling out renewables.

But there are plenty of other examples where states have rolled out renewables, and prices have remained the same or even fallen. Look at Texas, Iowa, North Dakota, and South Dakota in the charts below (there are more examples if you flick through the states on the interactive chart).

In fact, if we look at data for the US as a whole (select “US total” on the interactive chart), we can see that prices have gone down slightly while solar and wind power have grown.

More renewables do not have to mean higher prices. It can — and in many cases, will — mean lower ones. But, the lack of consistent trends and strong correlations across different states makes it clear that other factors play a big role in determining consumer prices.

Note that the data on electricity sources / shares is based on electricity generation only. It doesn’t include state-to-state imports and exports, which can have a significant impact on pricing. So this is about electricity generation, not necessarily consumption.

Hawaii, for example, has very high prices because has high and expensive imports. It's for this reason that I've excluded it from this chart and the others; as an outlier, it makes it harder to see any relationship between the other states.

There has been lots of discussion and commentary on California's high electricity prices (and how they can be reduced).

Here's one place to start.

Here in Sweden (where the grid is 100% renewable, mostly hydro, nuclear, and wind), electricity prices vary a lot not by state, but by electricity zone, with the depopulated (but high-renewable-supply) north 4x cheaper than the South, where most people live and where there isn't as much hydro or local supply generally. I live right in the center in a more expensive electricity zone and my electricity costs what the cheapest US states charge here. That's including the higher VAT tax we pay and increasingly high transmission charges to fund the build out of a more robust grid. In the North, electricity costs 1/10th or even 1/20th of what Americans pay. A reason for the regional disparity is that we do have a national (and region-wide) grid, but it doesn't have enough North-South transmission capacity to even out supply. That's something that the higher transmission charges are going towards funding in the years to come.

It's a good thing electricity is very cheap in Sweden, too, because we do use a lot of it, especially in the cold winters for heating. Unlike in the United States where natural gas and fuel oil can predominate for heating, almost all heating here is from efficient, electricity-powered heat-pumps. It's really strange to me that that technology, which has been operating at scale in the Nordics for 30-40 years, is really niche and considered insufficient in the US. Why wouldn't people in those states with cheaper 12-cent electricity take advantage? Even if you use a less high-performance Nordic-style system adapted to Arctic cold, you can install a lesser one very cheaply that would perform very well for more mild winters in the Southern half of the US. And, many of the cheaper air-source systems also operate as an AC, too!

Thanks Hannah, extremely useful, and articles where the conclusion is "there is no correlation" are especially valuable because they are rare.

You say you are cautious about cross-country comparisons, but Bjorn Lomborg had a piece in the WSJ where his chart showed a very clear and positive correlation between share of renewables and price of electricity across countries (what Joel was asking in another comment), and I am curious if you have a view on it: if his data are correct, is there a reason why we see such a clear correlation across countries but no correlation across US states?

Thanks again for a great post